All photographs by Nell Farrell while living in San Felipe del Agua, Oaxaca, Mexico. See project statement.

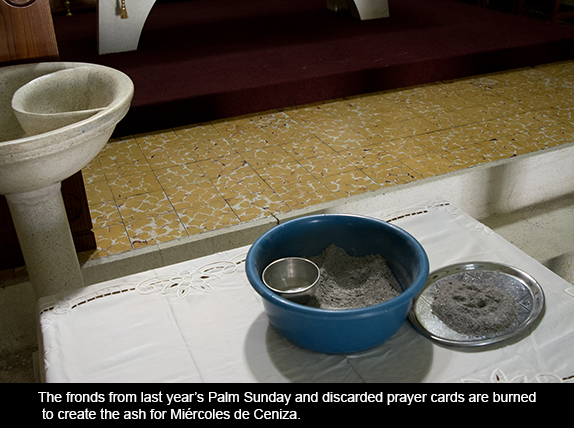

Growing up in Santa Fe, what I didn’t know was that the striking cross my schoolmates wore on their foreheads every Ash Wednesday was primarily a tradition of Catholics in English-speaking countries. In San Felipe, Oaxaca, the ash is sprinkled over the head, leaving a patch of what appears to be gray hair amid the black, not visible from the front.

Only about twenty-five people attended the morning Mass (perhaps three men, the same number of young women, and the rest middle-aged or older women), some of whom allowed me to make their portrait as they left the church.

Instead of meditating on a topic such as humility, Father Salvador set a challenge: do charity work for penance in observance of Lent. In conversation earlier he had explained that Lent is a time to atone, take stock of your life, put aside hates, and reconcile with God and others in preparation for Easter Sunday. (The example he used for reconciliation was the local strife between avecindados and nativos, newcomers and those born in San Felipe. My friend Blanquita, for example, lives in San Felipe and owns a very popular juice stand near the park there but attends church in a different neighborhood, saying she doesn’t feel welcomed by the nativos.)

The priest also drew me a diagram exploring the convergence of what he referred to as pagan rites and Christian ones. He is trying to put an end to the former—he is new to the parish, with less than a year under his belt—citing how much drinking occurs on Palm Sunday after the church-related activities have ended. He divided the paper into two halves, pre- and post-conquest, and described how the 500-year-old Catholic practices have become inseparable from the pagan ones, hundreds of years older.

Father Salvador discussed Day of the Dead in the context of the ancient tombs replete with food and clothing, and stated that attending church on that day, or asking the priest to pray for your dead, is enveloped in the “pagan” practice of taking food and flowers to the cemetery; they are equal. His explanation went some way toward an answer in my quest to understand how popular religious celebrations are expressions of faith: that cohetes and castillos and monos de calenda (firecrackers, towers thereof and processional puppets) are religion, as much as is prayer. It was not clear to me yet how this applied to the upcoming season of Lent and Holy Week, but I would find out.

Project Statement: The del agua in “San Felipe del Agua” refers to the fact that a portion of the water from which the colonial Mexican city of Oaxaca lives, flows down from the gem green hills behind what was once a town but now exists as the edge of the larger city: lambs, donkeys, tropical flowers, and a half-hour bus ride to the center of a cosmopolitan metropolis. Those born in San Felipe have a separate set of rights and responsibilities to the community than those who move here. Those who move here tend to bring wealth, and often live behind high walls and drive dark-tinted SUVs.

My family and I lived in Mexico for one year and chose San Felipe because we found a wonderful school there for our children. Having grown up in New Mexico I have always been attracted to Catholic imagery and Guadalupe, growing up atheist I have always been fascinated by faith. And so, in Mexico, I photographed our neighborhood parish.

The photo essays resulting from this study will be published in the New Mexico Mercury from October 2014 through June 2015, roughly once a month on the date corresponding to the event photographed one year previous.

March 17, 2015