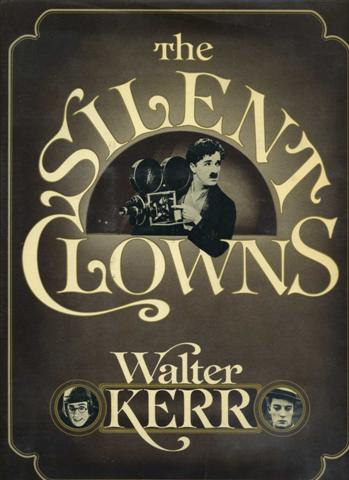

I love books about film. Motion pictures. In The Silent Clowns, Walter Kerr—a playwright and theater critic—explores the roots of comedy in Hollywood films. Of course the French were a little ahead of Hollywood, as Georges Méliès, an illusionist and filmmaker, who could be called a special effects master, sometimes called a “cinemagician,” seemed to already understand the medium thoroughly. One of his best-known films, A Trip to the Moon, was made in 1902.

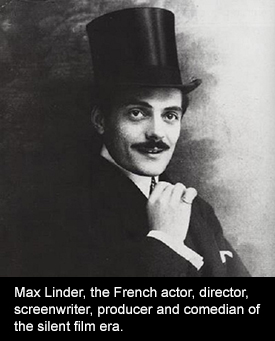

Following Kerr’s discussion of Max Linder, the French actor, writer, director, who had come to Hollywood and made three films, which he discusses in an attempt to trace the nascent ticklings of screen humor; then he turns to Mack Sennett:

Following Kerr’s discussion of Max Linder, the French actor, writer, director, who had come to Hollywood and made three films, which he discusses in an attempt to trace the nascent ticklings of screen humor; then he turns to Mack Sennett:

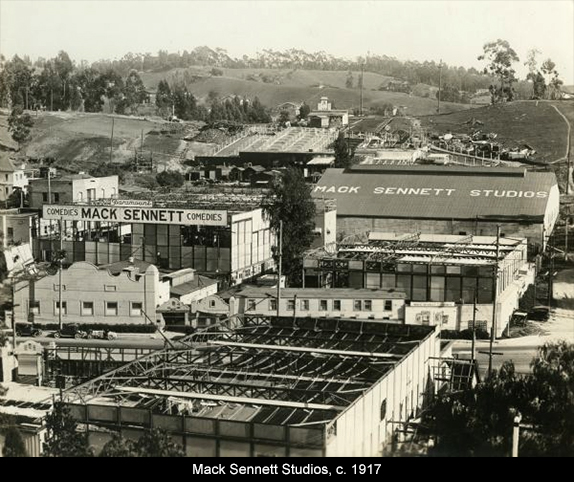

Linder went home to France, where, ill and discouraged by the relative unpopularity of his American films, he killed himself. A form in which he had excelled had inexplicably changed its tune and danced heartlessly away from him, requiring a new breed of clown to make the most of its invitations. The revolution is normally identified with Mack Sennett, and it is indeed Sennett who finally took hold of the form by the scruff of the neck, stood it on its head, and shook the gold from its pockets.

But Sennett did not give the form its quintessential American shape. So far as I can determine, D.W. Griffith did. This must sound strange; Griffith made very few comedies; his sense of humor was so undeveloped that even the rustic high-jinks of Way Down East were beyond him; and he hated slapstick and all its relatives…yet in at least one of his rare comedies he laid out the master plan for what would ultimately become ‘pure’ silent film comedy, offering its architecture and even its detail for an entire generation to copy.

He directed The Curtain Pole, in 1908, himself.

So in this insightful book Kerr argues away from Sennett as the King of Comedy and calls him “The Insensitive Master Carpenter”; further, he says that Griffith laid the foundations for silent comedy in the Biograph film mentioned above. Yet, grudgingly, as Kerr must do, he admits that Sennett took the form by the scruff of the neck, etc.

Mack Sennett was a colorful character that had escaped his bookies in New York and took his production company to L.A. This was at a time when there was no “Hollywood,” as Sennett’s studios were in the Silverlake district just off of Sunset Blvd. He drew comedians like Chaplin and Fatty Arbuckle and Mabel Normand to his stable.

In Sunset Boulevard William Holden’s character says about the pool in Norma Desmond’s backyard: “Mabel Normand and John Gilbert must have swum in it ten-thousand nights ago.”

In Sunset Boulevard William Holden’s character says about the pool in Norma Desmond’s backyard: “Mabel Normand and John Gilbert must have swum in it ten-thousand nights ago.”

What is amazing is that through adversity they all continued to make people laugh. For example, in 1922 Normand was a suspect in the murder of William Desmond Taylor, who had made fifty-nine silent films, and with whom she was involved; he lived on S. Alvarado and Mabel was on W. Seventh St. The crime remains a cold case in the LAPD files.

To garner another perspective from the erudite critic, Mack Sennett wrote his own book (as told to Cameron Shipp) in 1954. It’s a candid look at those early days. Here are a few excerpts:

I was a Canadian farm boy with no education. I moved to the United States and worked as a boilermaker…and I wound up a motion picture producer, many times a millionaire when I was on top of the heap. Where else but in America could a thing like that happen?

I heard there was money in motion pictures. As much as five dollars a day for professionals like me…I went down to 11 East Fourteenth Street [in Manhattan] and applied…The year was 1909…

My happiest and my saddest memory is Mabel Normand…[an] actress who ate ice cream for breakfast. I suddenly recall that she often read Sigmund Freud at the same time. She was the most gifted comedienne Hollywood ever knew.

In January 1910, Griffith brought Sennett to Hollywood, where he lived downtown at Georgia and 12th St. The population of L.A. was 319,198. And they were making two pictures a week.

Mabel, Fred, Ford and I arrived in Los Angeles in January 1912. We started making a motion picture within thirty minutes after we alighted at the Santa Fe station.

This collaboration led to the first movie, first pie throwing, first Keystone Kops, first million. The funnymen and women concocted masterpieces of exaggerated human conduct. The public loved it. The reality, not the myth: We did the best we could with what we had.

Sennett was an anti-intellectual. None of them had read extensively. Sennett downplayed his role as an artist—perhaps he’s just being honest. Uneducated, a son of the theater, uninterested in art or the questions of culture, but he tickled the American funny bone. The bottom line was the bottom line. And making laughs.

His original backers, Kessel and Bauman, were also his bookies, as I have said; they were shooting with illegal cameras, dodging the patent trust detectives and Edison’s men. Sennett was one of the great hucksters of all time. One of the men who made the movies.

There are more stories about the origins of the “small man”; the Harry Langdon story, and Chaplin’s start and first screen appearance 100 years ago—it was a flop. The second film was Kid Auto Races at Venice, which was the first time the Tramp appeared on screen.

Walter Kerr had Sennett’s book to use in writing his, and Sennett, in a look back, encircling the ring of comedy, admits that,

Max [Linder] was the celebrated French comedian whose pictures for Pathé Freres in Paris had influenced me as long ago as when I was working for Biograph and Griffith on Fourteenth Street. And there is no doubt his style had a considerable impact on Charlie Chaplin’s development as a comedian.

C'est finis!

September 10, 2014