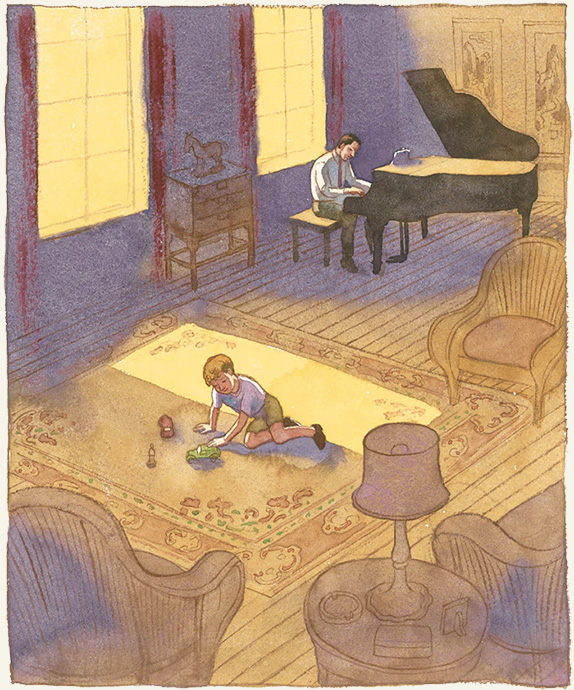

“…[T]he sun coming through the tall windows would be carved into clear rectangles on the carpet into which I would steer my trucks and cars as if they were entering a city of light.”

Leaving China: An Artist Paints His World War II Childhood is a memoir by designer and illustrator James McMullan, who has long been the principal poster artist for Lincoln Center Theater. I saw a few of the plays his works advertised when I lived in New York, but remember many of his posters. Like his posters, his illustrated memoir is clearly contemporary as well as vital and emotional.

Leaving China is categorized as a Young Adult book, targeted at teenagers. It would be a fine gift for any adolescent (especially young misfits), but it deserves a wider audience. It is the story of McMullan’s peripatetic life during the Second World War. He was born in China in 1934, the grandson of missionaries. During his early years he witnessed the Japanese Army occupation, sailed across two oceans, flew over the Himalayas, lived on an island in British Columbia and attended boarding school in India.

Each of over 50 pen and watercolor images is matched with brief and evocative text, akin to prose poems. It begins with McMullan’s earliest memory, which is of throwing a grape. The grape bounced back and he retrieved it—and was then attacked by the German shepherd after the same grape. He doesn’t know whether that experience contributed to his anxious nature, but he does know that his timidity was a great disappointment to his parents. He was not what they had in mind.

At its heart, the book he has written is about “…that nervous boy gradually finding his strength in art and a way to be in the world that was not his father’s or mother’s idea of a man’s life.” The boy is sensitive, attuned to beauty, and empathetic. Perhaps not the best characteristics in a businessman or soldier (his father’s occupations), but traits that prove useful in an artist.

His interest in art began with the traditional scrolls on the living room walls of his family’s home in Cheefoo (now Yantai), delicate watercolors in brown and ochre, monumental landscapes with clusters of tiny figures, images “…full of air and space... all so quiet and subdued, but somehow so alive.”

McMullan’s paintings contain similar air and space. Some images suggest individuals dwarfed by their environments or simply a child’s sense of scale. Some of the images are of events he never witnessed, interpretations of family stories or family photographs. Images depicting happenings in his own life are from the point of view of an outside observer. Often figures and objects are left unfinished, uncolored, as if his memories were an incomplete construct. The imprecision of watercolors may even suggest the malleability of memory. Shadows are shown as violet in his paintings, so that which lies in the shadows is visible.

His images and words combine to create a sensory experience—visual of course, but also aural and tactile. We can add the sound of his father “noodling” on the piano in the late afternoon and the feel of those rectangles of light—surely warmer than the surrounding carpet.

In McMullan’s memory of the Japanese “night runners,” he combines an image of the soldiers seen from his bedroom window, the curtains blowing in the breeze, with his vivid description of the sounds the runners made.

“Detachments of Japanese military, led by a soldier carrying a flaming torch, would pound down our narrow street just beyond our garden wall in a seemingly endless drumbeat of stomping boots and guttural chants.”

It is the unusual nature of McMullan’s experiences and that he included only those experiences that affected him emotionally or aesthetically that makes this memoir exceptional. There are no boring bits.

His young life contained abrupt separations, cultural dislocations and even potentially fatal encounters. When McMullan found a temporary safe harbor on an island in British Columbia, his relief was palpable. He was accepted by his relatives, made a good friend, and even had enjoyable adventures with his classmates.

He still needed time to be alone. One day, he took shelter in a small cave from which he looked out at the dark ocean and “..tried to imagine all the things that must be happening under the waves.” Then he experienced a wondrous sight, one he recreated nearly 70 years later.

“One day I was surprised by something I’d never imagined. The surface of the water lapping not eight feet away from me was broken by a huge killer whale, rising smoothly from below, first the dorsal fin and then the whole 30- or 40- foot length of its body.”

That was his peak experience on the island, but while living there he also glimpsed a life he liked and that he later built for himself—one with beautiful surroundings and a warm circle of family and friends. Walking home from school, he even observed an artist painting a picture, “a simple process that seemed strangely magical.” In the course of his life, McMullan mastered that magical process, and more.

The book can be read as an Albuquerque Public Library eBook. I read it for free and then ordered a copy. The print version is about 9”x 8,”made up of two-page spreads, with text to the left and corresponding watercolor to the right. A drop cap in color visually connects each page of text to its image. The pages themselves are ivory in color, a nice complement to the many violets and blues in the paintings. A sensory book like this calls for a sensory reading experience. Treat yourself.

July 15, 2014