For someone like myself, whose main activity has been sitting in front of a computer (before that, a typewriter) and exercising my mind, hiking to Kiet Siel in September of 2004 was a once-in-a-lifetime journey. I persuaded an extremely athletic friend from South Africa to make the hike with me; he carried 70 pounds to my 20. I remember the experience with deep gratitude. Even one year later I would no longer have been able to make the trek.

(Landscape near Kayenta, Arizona. Images by Margaret Randall)

(Landscape near Kayenta, Arizona. Images by Margaret Randall)

Kiet Siel is an Ancestral Puebloan ruin in what is now northeastern Arizona, not far from the little crossroads community of Kayenta. The National Park Service and Navajo Nation jointly oversee Navajo National Monument, where Kiet Siel, Betatakin, and Inscription House are protected from damage and destruction. The six-mile round trip hike to Betatakin can only be made accompanied by a ranger; during the spring, summer and fall there are usually two tours a day. Inscription House has long been off-limits to visitors; its fragility will no longer tolerate the intrusion.

Kiet Siel accepts some 20 visitors a day, from late May through September. Round trip it’s almost 18 miles, which some choose to do in a day but the majority divide between two. A small campground and solar-heated pit toilet near the ruin allow for an overnight stay. Visitors must attend an orientation meeting the day before heading to Kiet Siel, at which instructions regarding signage, difficulties, and hiking protocol are given. Without the permit granted at that meeting, you can be expelled from the canyon.

(Sandstone formation in Tsegi Canyon)

(Sandstone formation in Tsegi Canyon)

(One of several waterfalls)

(One of several waterfalls)

I had friends who many years before had reached the ruin on horseback, but that’s no longer permitted. The horses and cattle belonging to the Navajo people in the area can be seen by hikers, but it’s felt they are enough livestock in terms of wear and tear on the land. From the Navajo National Monument headquarters to the ruin itself you descend into Tsegi and then Kiet Siel canyons, cross and re-cross a streambed patched with quicksand, scramble over rocky shelves and make your way through narrow passes. In the seasonal heat one gallon of water per day is mandatory. On the way in we stashed bottles by rocks or recognizable features of vegetation, retrieving them on our way out.

Kiet Siel was first occupied around 1250 AD, during a time in which many such communities sprung up throughout this part of the American Southwest. Between 1272 and 1275 there seems to have been a construction boom. There is no evidence of any building beyond 1286, and the location is believed to have been abandoned some 20 years later.

(Ancient pots sitting on a ruin wall)

(A cache of corncobs chewed clean)

(A cache of corncobs chewed clean)

Among the Kiet Siel’s compelling features is the fact that a number of objects—utensils and tools—remain en situ. A ceramic pot may not be placed exactly where the last occupant left it, but seeing it on a low wall nevertheless produces a sense of awe. Grinding stones evoke images of women pulverizing the grain and then handing it off to other women whose job it was to achieve a finer grind. Dried corncobs gathered in a hollow of stone transport the visitor to the time when they had only just been chewed clean by someone sitting by a fire. Even piles of petrified feces bring one closer to Kiet Siel’s original inhabitants.

When most of the approach hike was complete and we’d reached the little campground, we unburdened ourselves of our packs and made one last river crossing to the Hogan where we knew an on-duty ranger would be waiting. We had been advised to cough politely, in the Navajo way, to let the ranger know we were there. Soon he emerged and told us to wait a few minutes while he got his things. Then he accompanied us through one last thicket of underbrush. When we emerged on the far side, we were looking up at the impressive ruin.

(Seventy foot ladder leading up into the ruin)

(Seventy foot ladder leading up into the ruin)

Its broad walkway, approximately 160 rooms, 6 kivas, and one round tower are in an amazing state of preservation. Mancos rancher and explorer Richard Wetherill is believed to have been the first non-Indian to stumble upon the ruin, in 1895. Opposing views exist about the number of objects Wetherill took from Kiet Siel and the other sites he “discovered,” and what became of those objects. Some say there were tons. We know he sent some to the Smithsonian, some to Denver, and others to the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair. He always said his aim was to garner official interest in these ancient peoples so the government would protect the sites.

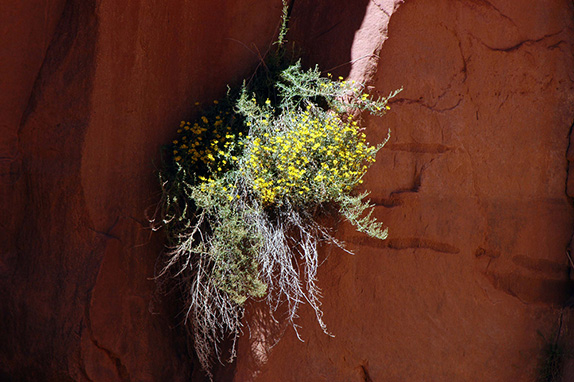

(Wildflowers growing from a crack in the rock)

(Wildflowers growing from a crack in the rock)

For years a burgeoning archeological community downplayed Wetherill’s importance and denigrated his treatment of the ruins and their contents. More recently, though, he has been vindicated. Although not trained as an archeologist himself, the methods he used to dig and unearth were not that much worse than those used by experts at the time. From his writings we know how deeply he loved what were then called Anasazi ruins and the culture they embodied.

It is fortunate for Kiet Siel that when major reconnaissance took place the decision was made to stabilize rather than renovate. I am the proud owner of one of three extant copies of the ruin’s Stabilization Records, hand-typed and with many pages of photographs—one of what each room looked like before any work was done and another of that room after miner repairs. This work was overseen by archeologists Roland Von S. Richert and R. Gordon Vivian along with seven trained and experienced Navajos from the vicinity of Chaco Canyon, New Mexico. It was begun on September 12, 1958 and completed 9 days later. Like some gift from the Ancients, my brother, who is a rare book dealer, found this copy of the Stabilization Report at an estate sale, and surprised me with its wealth of information.

(Turkey pictographs)

(Turkey pictographs)

When we stood with the ranger, looking up at the ruin on its high ledge filling the broad alcove, I immediately saw the wooden ladder I would have to climb to gain access. Seventy steps (I counted them) against an almost vertical cliff wall. I had learned of this ladder in the orientation meeting the day before, but had banished it from my consciousness while battling hot sun, tricky quicksand, and hiking exhaustion. Now I had no choice but to move forward, and up. I gripped the ladder’s rungs so tightly I ended up with splinters beneath my skin.

Once on the wide walkway fronting the ruin itself, exploration was pure delight. A number of pictographs and petroglyphs are painted and incised on the back wall. One shows several turkeys. Many of the kiva roofs are still intact, or partially so. I could feel my heart pounding, and a slight tremor in my hands produced more than a few slightly out of focus photographs. In photos taken by my friend I can see the evidence of my exertion in a half moon of sweat covering my shirtfront.

(Partial view of Kiet Siel)

(Partial view of Kiet Siel)

I listened as if in a dream to the ranger talking about the people who built this place, their life here and what may have induced them to leave. The long trunk of a tall white pine leans across the ruin’s entrance/exit point, as if to close it off to those who might arrive later or define some boundary we cannot know.

There are a number of conflicting ideas about the abandonment. Archaeologists agree that there was a definitive and well-defined exodus from this region at the end of the 13th century. Between 1276 and 1299 there was a distinct decrease in the amount of annual precipitation; this period was known as the Great Drought. With so little rainfall in an already arid environment, there is no doubt the people experienced increased stress; crops upon which they depended would have been vastly reduced. There is also evidence of the beginning of an episode of deep arroyo-cutting, that would have damaged what was left of the usable agricultural land. There would have been a lowering of the water table as well.

Anglo scholarship and Navajo and Hopi memories disagree, however. According to Hopi oral tradition, the area known as Wunuqa (modern day Tsegi Canyon) was abandoned as part of a spiritual quest. In particular, the Snake and Horn clans inhabited the area now known as Navajo National Monument. Hopi legend has it that the Horn Clan forced the Snake Clan out, due to Snake Clan children biting other children and causing their death. This may be an allegory for some important historical event that caused the people to leave.

Before we descended once more to the canyon floor, I stood for a while looking out at the delta where the inhabitants of Kiet Siel planted and harvested, collected nuts and wild berries, and hunted small animals. I wondered what a child standing where I stood might have thought about the circumference of her world. Did she imagine it ended where the canyon turns? Would she ever have walked beyond that point?

(View from ruin of Kiet Siel Canyon)

(View from ruin of Kiet Siel Canyon)

We spent a couple of hours in the ruin. That night, it grew cold. We huddled in our sleeping bags, conjecturing about life in this place seven or eight hundred years before. The spotless little solar toilet retained the heat of the day, and visiting it almost made me want to stay. The next morning we walked out slowly. Climbing the 1,000 feet from canyon floor back up to the Shanto Plateau was the hardest part, but worth every painful step. I felt as if I had been privileged to view something few others see, both because these ruins cannot last forever and because I knew that I myself was reaching the end of that period in my life when such a hike would be possible.

Indeed, fewer hikers have reached Kiet Siel since it’s been open to the public than visit the ruins at Mesa Verde on any given day.

(Author at Kiet Siel)

(Author at Kiet Siel)

May 31, 2013