Editor's note: This photo essay is the third in a series by New Mexican photographer Nell Farrell, produced while living in Oaxaca, Mexico for one year. See project statement.

In Oaxaca people have been walking for days. Pilgrims from around Mexico travel to the town of Santa Catarina Juquila to venerate the original statue of the Virgin of Juquila. December 8 is the Feast of the Immaculate Conception of Mary, which Juquila represents. Especially beloved in her home state, her likeness is venerated in many towns and barrios by those who will not make the pilgrimage; these photographs are from San Felipe del Agua, from both the parish church and one of its neighborhood chapels for which she is the patron.

Her history is this: A Spanish priest come to convert brought a diminutive Mary (one foot tall) to the hills of Oaxaca, and when he left he gave her to a devoted indigenous disciple there. One year, when the people burned their croplands before replanting, as they always do, the blaze got out of control and engulfed the simple chapel that housed Mary. She emerged a bit smoke damaged, thus brown of skin, but otherwise unscathed. The faithful began to travel to see this little statue. Now she draws millions each year.*

In the barrio where I lived, in the city of Oaxaca, the drama of the pilgrimage was shortened to a procession up a steep hill between the church and the home of the day’s mayordomo (the person honored with the responsibility of providing for the celebration). Afterwards, I visited the chapel built in her name, where a mass was held and everyone feasted.

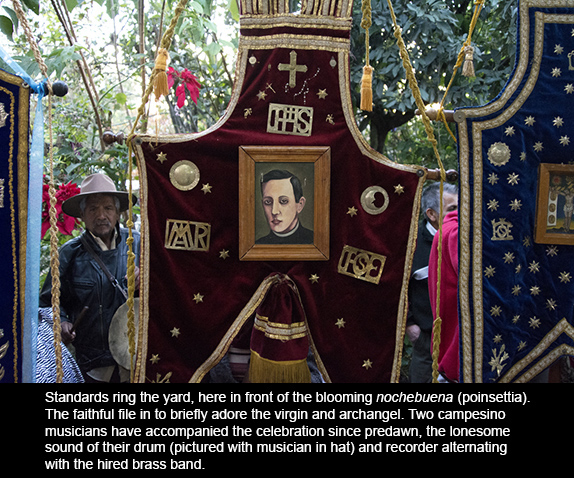

In the early morning, the band gathers in the dark, and the people arrive and go into the church. Many carry standards, red banners with gold studs and braid, the image of a virgin or saint in the center. They are stacked against the inside walls of the church now, held erect by hefty wooden poles, some quite large. Many men have a leather strap over their shoulders with a small pouch at the end to help them support the pole, though many do not use theirs. Against the church wall, other men prop even taller sticks, for which I cannot figure a use; at the top of them seems to be some sort of crucifix, something very homemade-looking.

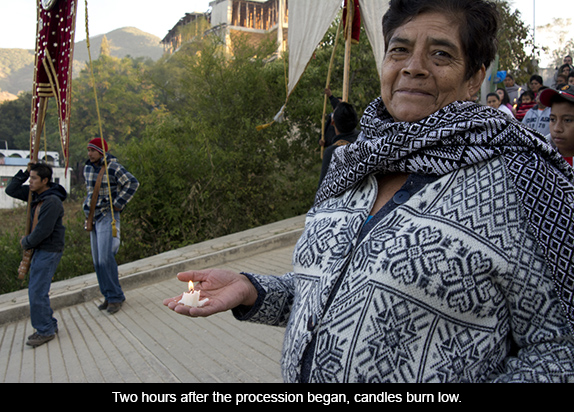

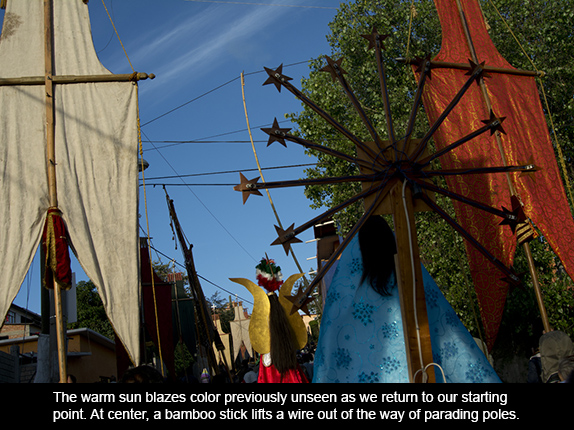

The cohetes (firecrackers) this week have been louder than any I have previously heard. Church bells mark time. They have been tolling all week. All morning. They woke me at 3:30 a.m., then called frantically at 4:45. When the procession begins at 5:15, the banners form a long line of elephants casting tall shadows in the blue streetlights. The archangel and virgin are dwarfed, though she sports a halo of stars and Christmas lights with a battery pack strapped on the back. The women carrying her are dressed impeccably and traditionally, and made up, while the rest of us are barely out of pjs. Is their regal carriage a function of supporting the bulky wooden table upon which the statue is mounted? All four of them wear matching flats, which I imagine new for the occasion. One puts her hand in front of her face anytime my camera nears.

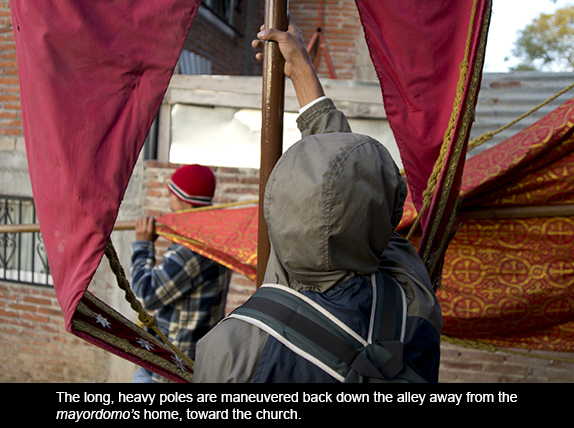

Two young men have especially heavy standards, and multiple times down every street they do a sort of circus act dance—they lean back, the weight of their load keeping them upright, and bounce, squatting near to the ground to lower their burdens until they have passed under another telephone wire. I am impressed by the resilience of tradition—they will carry the banners at the appropriate height, hassle or no. And I discover the use of the tall bamboo sticks with what turns out to be a T at the top: to hoist the tangle of wires overhead out of the way one by one.

We walk along to the soft incantation to the virgin:

Bendita tu eres entre todas las mujeres y bendito es el fruto de tu vientre.

(Blessed are you among women, and blessed is the fruit of your womb.)

Amén.

In the dark morning, I cringe on behalf of all of us in attendance. For the implicit criticism of being human, not being virgins, just cold and a bit disheveled, but attentive, carrying families forward. The sex and childbirth of course are prescribed, as well as desired, but certainly not immaculate. For the Mexican Catholic women here, celebrating an ideal womanhood must provide a strength or balm.

The procession terminates at the home of the mayordomo, where a huge tarp covers a dirt courtyard and everywhere are the sky-blue and white decorations that have marked our way. Musicians play, then we traipse back down the road, past the chapel, and back to the church. The standards are set down, and we retrace our steps, down the hill and up: the mayordomo will provide breakfast. Now long rows of folding tables fill the courtyard. Waitresses with big trays serve pan and chocolate de agua in rough brown clay bowls. The band prohibits small talk. A bowl of something that seems like either pig or chicken with an unusual texture is served, but I can only stomach the broth, soaked up with a warm tortilla.

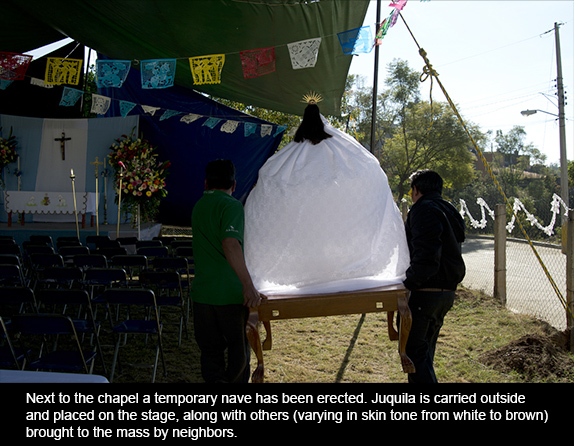

On the way back to town I stop in at the chapel. They are preparing for a 10 a.m. open-air mass. As people arrive, the virgins on the dais multiply: families are setting down their own Juquilas in a row. The one from inside the chapel is brought out, in a long, beautifully embroidered gown; she is endearing in her tininess. A women’s choir settles in along the edge of the rows of folding chairs. They too are outfitted in crisp blue and white. As I am photographing them preparing their song sheets, Father Salvador arrives and tells me to photograph now, as I may not during mass. He has already forbidden me from taking pictures during services inside the church, but Mauro, who oversees the chapel, had said it would be fine here. The priest does give me a good tip, though, by suggesting I photograph the higadito. This turns out to be the dish I was served for breakfast up the hill. They will eat it here too, after the mass.

I find a hut towards the back of the property, where a number of elderly women are stirring vats of food, preparing both breakfast and lunch. Mauro invites me to stay all day. He smells of alcohol and has apparently slept very little the last couple of nights. The celebration began Friday night, going until 4 a.m., and is not over yet. Despite his rough shape, he is running this event. He built this chapel. The mass will take place in front of his home. He does this every year; preparations for next year begin upon finishing this one. The humble façade of his house stands in stark contrast to the gleaming white, spotless chapel, and I am reminded that around the world there are hamlets like this, where the homes of all are dwarfed, in size and opulence, by the church.

* Sources

America: The National Catholic Review

Project Statement: The del agua in “San Felipe del Agua” refers to the fact that a portion of the water from which the colonial Mexican city of Oaxaca lives, flows down from the gem green hills behind what was once a town but now exists as the edge of the larger city: lambs, donkeys, tropical flowers, and a half-hour bus ride to the center of a cosmopolitan metropolis. Those born in San Felipe have a separate set of rights and responsibilities to the community than those who move here. Those who move here tend to bring wealth, and often live behind high walls and drive dark-tinted SUVs.

My family and I lived in Mexico for one year and chose San Felipe because we found a wonderful school there for our children. Having grown up in New Mexico I have always been attracted to Catholic imagery and Guadalupe, growing up atheist I have always been fascinated by faith. And so, in Mexico, I photographed our neighborhood parish.

The photo essays resulting from this study will be published in the New Mexico Mercury from October 2014 through June 2015, roughly once a month on the date corresponding to the event photographed one year previous.

December 08, 2014