Stupid men who accuse women without reason,

unaware you are the cause of their shame:

you who in your desire treat them with contempt,

why demand their piety if you incite them to sin?

Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz[1]

In the world of Spanish and Latin American letters, there is universal agreement that Juana Inés de Asbaje y Ramírez de Santillana (1651-1695), popularly known as Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, was one of the greatest writers of the language. She was revered for her poetry, written in several languages. Her face appears on Mexico’s 200-peso note. She is published in dozens of translations, there are many books and several films about her life, and the convent in Mexico City where she lived and died bears a mysteriously shifting aura of her cloistered time on earth, her daily activity, and the magnetism she exudes even today.

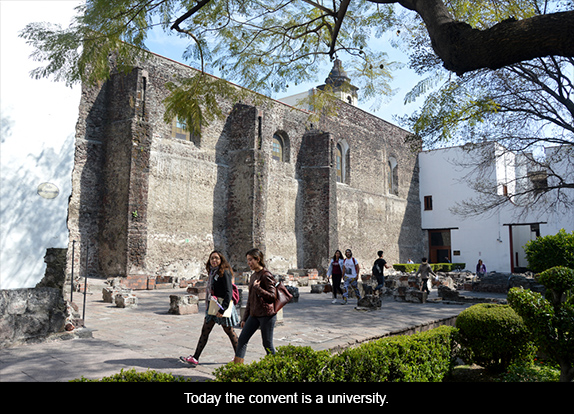

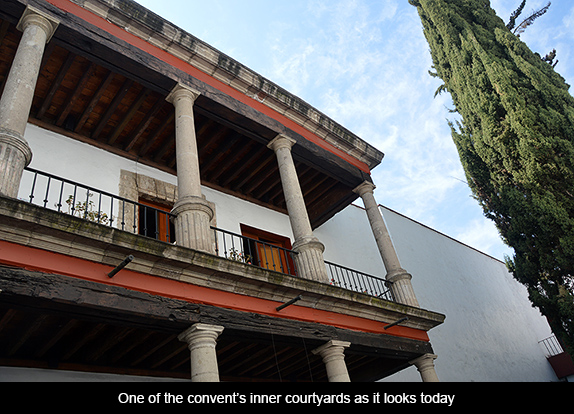

I visited the cloister in search of Sor Juana. It is a university now. Young people fill classrooms and stroll through the colonial courtyards. I wanted to sense the poet’s powerful presence, walk where she walked, hear her voice. The construction itself has gone through many phases, from its 16th century origins through an 18th century neo-classical reconstruction to what’s left today of its physical history. Preserving such a building in Mexico City presents challenges. Although massive, the very earth on which it stands—filler on what was once a great lake—has shifted through the centuries. Brutal earthquakes have also taken their toll. Through an opening cut in the floor of what is now an office, we could look down on the capitol of a stone column that once supported the roof.

The cell inhabited by Juana probably no longer exists. Since her death, it was used variously as a shop, an apartment, a warehouse and parking garage. Much research has gone into trying to determine exactly where the great poet’s quarters were. Writing in which she mentions looking through her window at them, would indicate that she resided in the wing from which the city’s iconic volcanoes—Iztaccíhuatl and Popocatéptl—can be seen in the distance. The great Mexican poet Octavio Paz, who has written extensively about Sor Juana, came to this conclusion. But even this is not certain. Modern buildings have risen up to change the landscape.

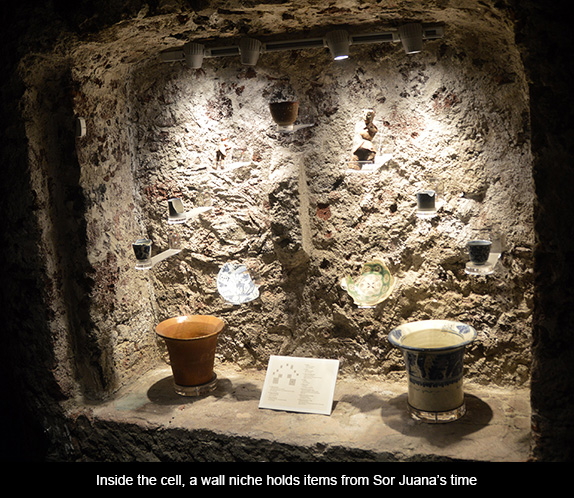

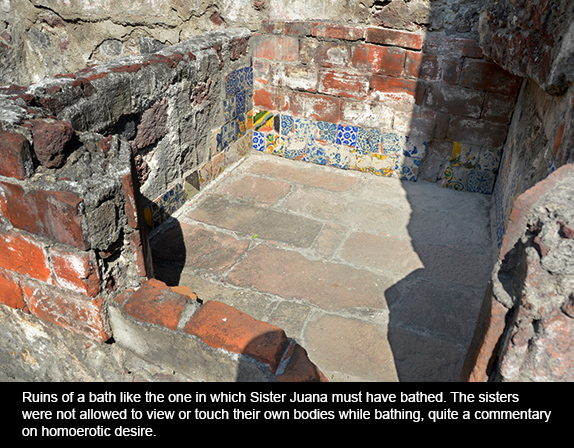

Because of this uncertainty, the keepers of her story have designated a cell in representation of the authentic one. To call it a cell is misleading. Despite being cloistered, Juana lived in relative luxury. She had at least one female servant, and an apartment of rooms, including one that housed the largest library then existent on the continent. There was a bedroom, sitting room, small kitchen, bath, and the study in which she wrote or dictated to her servant (which also held a great many scientific instruments such as a telescope, an astrolabe, and other devices she employed in her constant studies).

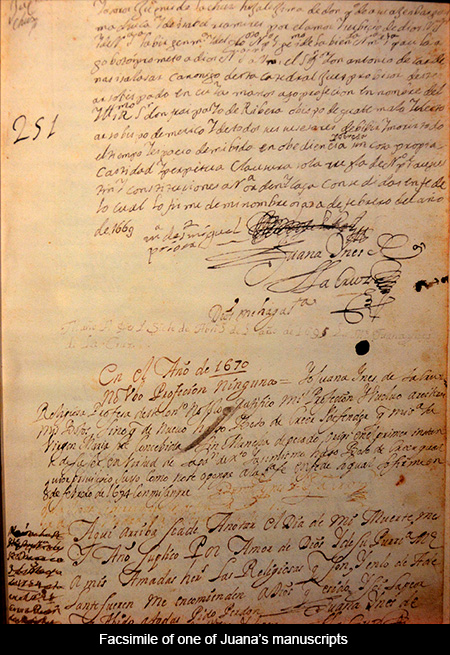

The cell one can visit today is more symbol than reality. The ancient stonewalls give a sense of her physical surroundings. Several showcases display a few broken dishes and other items from her time. Fragments of her manuscripts grace the walls. Still, I felt a strong, even physical, connection with the poet: what part an energy that doesn’t die, what part longing, I cannot say.

Once inside the representational cell, the most moving museum offering is an animated slide show that moves across those stonewalls. It emanates from several projectors situated in different parts of the space. Sitting on a wooden bench in semi-darkness, viewing it is a dramatic experience. The images are stylized and convey a sense of the woman’s life. The music is evocative of the era and the narration is constructed entirely of lines from Juana’s poetry. When the dim lights came back on, my friends and I remained silent for several minutes, completely trapped in the aura created by such a multidisciplinary and beautifully executed work.

Juana was born in a Mexican village called San Miguel Nepantla, now Nepantla de Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, in her honor). She was the illegitimate child of a creole woman and Spanish military captain. The latter would remain absent throughout her life. Her baptismal certificate describes her as a “daughter of the Church,” the euphemism for illegitimacy in that time and place. She was raised in nearby Amecameca, where her maternal grandfather owned a large country home. She wasn’t poor, but neither did she belong to the privileged world of royals or have some other sort of social status that might have enabled her to gain even a backdoor access to the realm of books.

What we know about Juana’s childhood is that she hungered to learn, something off-limits for girl children in her day even if they were born into a higher class. She is said to have hidden in the chapel of her grandfather’s home so she could spend hours in its adjoining library. She taught herself to read at the age of three, and by the time she was five could do simple mathematics. At eight she wrote a poem on the Eucharist, by adolescence she had mastered Greek logic, and at 13 she was teaching Latin to other young children. She also knew some Nahuatl, the language of the ancient Aztecs, and wrote poetry in that language. Later, as an adult, she would produce poetry and drama in several languages.

Everything that comes down to us about Sor Juana emphasizes her fascination with the greater world: literature, history, science. Yet in order to gain entrance to that world she had to retreat to a convent, where she was subject to the Church’s cruel power over women and arbitrary determination to decide who may have voice and who not.

When Juana was 16 she wanted to disguise herself as a man so as to be able to enter the university. In her day women had two choices: they could accept the slavery of conventional marriage or enter a convent. Juana first went to live at the Convent of Barefoot Carmelites in Cuernavaca, an order where the sisters did menial work, sold their wares in the market, and so forth. It was a hard life, filled with sacrifice, and it diminished her health.

Soon her insatiable curiosity, urge to study, and conversational brilliance came to the attention of the Viceroy’s court (the representative of the Spanish crown in Mexico). She then moved to a different order of Carmelites in Mexico City, the convent of Santa Paula de Hieronymite, where she was able to gain access to a life of the mind. She refused several marriage proposals, and remained cloistered for the rest of her life.

The Viceroy and his wife were fascinated by the 17-year-old who espoused such unusual intelligence, and they befriended her. They arranged a meeting—a kind of test—at which outstanding theologians, jurists, philosophers and poets questioned her on a variety of subjects. She acquitted herself so well that she was sought from then on as someone who could be counted on to write, discuss, and contribute to the intellectual life of her time. One of her friends, Don Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora, who was known as a savant, visited her in the convent’s visiting room, and she even sustained professional discussions with Isaac Newton.

Sor Juana’s writing was richly baroque. It contained a passionate and subversive defense of the rights of women to study, teach, and write. It predates by a century and a half literature anywhere in the world that laid bare the subservient role of women in society and advocated for their education. Ilan Stavans, who has written extensively about Sor Juana’s work, says it is “a cornerstone of Hispanic-American identity […] at once a chronicle of the tense gender relations in the Western Hemisphere, a rich portrait of the social behavior that prevailed more than a century before independence from Spain was gained in 1810, and the very first intellectual autobiography written by a criolla in a hemisphere known for its solipsism, introversion, and allergy to public confessions.”

Sor Juana was also playful and full of fun. When a portrait artist traveled from Spain to paint her picture, it is said that she got the prettiest novice in the convent to pose in her stead. Although the large oil hangs in a prominent place in the cloister, neither the name of the model nor that of the painter are known to us today. Interestingly, the artist too was a woman.

It was the Viceroy’s wife, Lady Leonor Carreto, who developed a singular relationship with Juana. She encouraged and supported her. Some believe they had a romantic relationship. When the Viceroy was suddenly recalled to Spain, Juana lost her greatest protectors and benefactors. This was a blow from which she would not recover. They did bring some of her writing home with them, though, leading to her being published in Spain before her work appeared in Mexico.

Needless to say, Juana’s intelligence was as dangerous as it was fulfilling. On the one hand, she loved the learned life and those who were stimulated by her mind valued her many talents. On the other, the Church, always ready to oppress women especially, never ceased trying to confine and punish her. Her personal confessor betrayed her. The bishop of Puebla, Manuel Fernández de Santa Cruz, published Juana’s critique of a 40-year old sermon written by a Portuguese Jesuit named Antonio Vieira. He printed it without her permission, but although it bore a pseudonym it was clear that it was hers; no one else could have penned it. This brought her unending troubles. She was commanded to devote herself to religious issues rather than secular ones from then on.

In response, Juana wrote her famous letter, “Reply to Sister Philotea” (also a pseudonym), in which she defended a woman’s right to education. She signed the document “Yo, la peor de todas” (I, the worst of all women). A film by the same name, written and directed by the Argentine filmmaker María Luisa Bemberg, is the best I’ve seen about her life. It not only gives us a sense of her contradictions and brilliance, but also shows us a time in which the Church had the power to make and break.

Juana was as pious as she was innovative. She was forced to give up her extensive library, consisting of more than 4,000 volumes (many of them hand-written). Her personal treasures were taken from her, including all her musical and scientific instruments.

A typhus plague raged through Mexico City then, and hit the convent hard. In the 17th century any severe fever meant death. Centuries would pass before antibiotics were discovered (today their overuse presents another danger). Juana nursed the sisters who fell ill, eventually contracting the disease herself. She died of it in 1695.

The life of this 17th-century religious sister remains filled with mystery. Innumerable books have been written on her life and work. Since the second wave of feminism, some researchers have explored the relationship she had with Leonor Carreto, citing its passionate nature. Poetry and prose written to her benefactor are, in fact, highly sexualized. We think of women-loving women very differently today; back then, the term lesbian didn’t even exist. Because Juana’s entire existence was so “other” to anything I know, I hesitate to place a label on their relationship.

Other biographers have concentrated on her powerful thrust toward learning, and the lengths to which she had to go to claim the life of intellect she needed. Juana Inés de la Cruz was a woman among women, a writer among writers, and a profoundly moving example of a spirit that would not be chained.

[1] The first verse of “Stupid Men.” Translation by Margaret Randall.

January 22, 2015