This is the second of two columns on the idea of home.

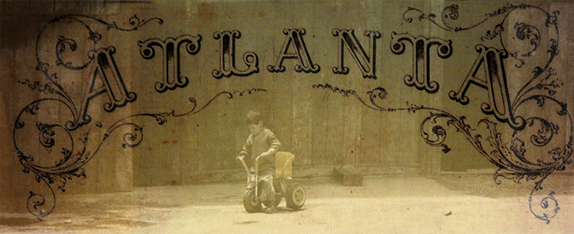

Home, it is said, is where the heart is, but it is also where the body is. During my childhood, my body was at an address I still remember—1624 Peachtree Street in Atlanta, Ga.—while just about all of my subsequent addresses have totally disappeared from my memory.

That early home was on the northern fringes of a small, relatively isolated town that was not yet a metropolitan area and mostly lacked suburbs. The house had been constructed and expanded in bits and pieces, like many an old house built when times were hard during the Great Depression.

It no longer exists. Where once there was a rambling white wooden country home with a rose garden in front amid a couple of acres of sloping grassy lawn, now there is a parking lot for a hig hrise office building.

For the family of five inhabiting that house, times were no longer hard but still none of us wanted to be living there, and each of us arranged to leave it. My mother, who grew up in Miami, and my father, who grew up in small towns in Alabama, met in Atlanta and made their life together there, but they never seemed at ease in the place. This business-oriented communications hub that had been destroyed in the Civil War, and still commemorated every fire and shell contributing to that destruction, was not their city and the Civil War was not theirs to refight. Margaret Mitchell may have been the city’s heroine and most famous resident while I was growing up, but we never had anything to do with her and her emotional romanticizing of a terrible past.

My older brother, the troublemaker in the family, happily escaped to Riverdale High School, a boarding school in New York City, at the ripe old age of 14. I eagerly took the train to Exeter in New Hampshire a month after my own 14th birthday. My younger brother, who had skipped a year in elementary school, joined me at Exeter two years later, when he was only 13. My preceding him eased his way into the school but made it harder for him later, and he eventually transferred to a school in Connecticut.

Within months of my departure, my parents picked up lock, stock and barrel and moved to an apartment in New York City, where they remained for more than a quarter-century, until my father died of cancer and my widowed mother moved to Santa Fe with me. The excuse for the sudden move to New York was a good job offered to my father, but both of my parents had long felt alien in their small, parochial home town.

My mother was a painter and a ballet dancer in a town that had little interest in either. They bought season tickets to Georgia Tech football games because it was socially de rigueur but were more comfortable spending Saturday afternoons at home listening to the radio broadcasts of the New York Metropolitan Opera.

Racial tensions were then bubbling to the surface in the wake of the Supreme Court decision desegregating public schools. Atlanta adopted the slogan, “The City Too Busy to Hate,” implying that if they weren’t preoccupied with making money, Atlantans would prefer to get on with their hating. My father was not a hater, but some of his Atlanta business associates were, and the animosity, at work and in society, left my parents more isolated than ever.

So much for Atlanta. None of us ever looked back.

Yet…I was miserable in that first home and could not wait to get away. I studied hard in school, not because I had a thirst for knowledge but so that I could get into a good Northern school where, unlike applicants with which I was competing, I had no ancestors who were alumni and my parents had no pull.

And yet…Although I felt like a prisoner in that home, it was also a symbol of safety and security, a place where I was protected from the buffeting of the larger world around me that I neither trusted nor liked. This town of racial and class and religious intolerance was also a close-knit community where those who maligned and assaulted each other rubbed shoulders in its schools and stores, on buses and trolleys, and on its streets. I could never figure out where or even if I belonged in this place that always seemed threatening to me.

Thus the home in which I was miserable was my only haven in a hard environment. If you hate the place you love, you’ve got a problem. I had a problem. It started at the very beginning. What was home, the idea of home, the reality of home? It took me half-a-lifetime to work it out, until, a couple of months before my 50th birthday, I was ready to settle into a new home, my first and, I hope, my last real home.

Settling is an odd word for the life my wife and I have led. We have traveled throughout the United States and to dozens of foreign countries, grabbing greedily at every opportunity to explore new places just over the horizon from where most tourists go.

Yet…There is sense to what may seem senseless, and it is this: Travel means not only leaving home but returning to it. The home we have is the more precious because we are not tied down, not rooted in place, not forced by emotion or circumstance to stay there. We leave because home is only a part of our world, and we return because it is indeed part of our world.

(Image derived from graphic by Greg Foster and photo by Sukanto Debnath / CC)

February 28, 2015