On the eve of the 68th anniversary of the dropping of atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, historians are still unable to answer the most basic questions: Who decided to drop the bombs, why were they dropped, why were they even built?

As part of the celebration of the 70th anniversary of Los Alamos, UNM emeritus professor of history Noel Pugach gave a lecture at the Bradbury Science Museum in Los Alamos summarizing what is and is not known about the first use of the atom bomb, and a few days later he elaborated on his findings in an interview conducted in his office on the UNM campus.

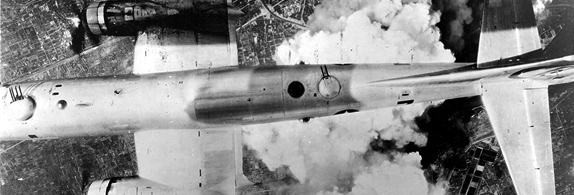

On Aug. 6, 1945, the U.S. dropped the bomb on Hiroshima and three days later on Nagasaki. In the decades since, the mysteries about the decisions have only multiplied the more researchers have delved into documents and the memories of those involved.

“President Truman created a myth that he formally ordered the dropping of the bomb,” is among the most controversial conclusions that Pugach has arrived at. There is no document or eyewitness statement that Truman gave any order, written or even verbal, to use the atomic bomb.

The only thing on the record—even in Truman’s two-volume memories—is that Secretary of the Army Henry Stimson and Army Chief of Staff George Marshall showed Truman a memo they had jointly written describing plans to use the bomb.

They had selected a number of possible Japanese targets, including Hiroshima and Nagasaki, based on two factors: The cities had not been previously bombed, so that damage from the atomic bomb would be readily apparent; and they contained at least a small military installation or industrial plants, thus making them military targets under international law.

Even more in doubt that the decision to bomb Hiroshima was the decision to use the second bomb, the one built at Los Alamos and tested in July 1945 at Trinity, to attack Nagasaki. No less of a person than Truman himself told an interviewer in the 1960s that he regretted not having given Japan more time to react to Hiroshima before destroying Nagasaki.

“If you wanted to show the power of the atomic bomb,” Pugach says, “you had to destroy something meaningful.” At first Kyoto, Japan’s most historic and artistic city, was favored, but Stimson eventually ruled it out. “I’ve been there,” Pugach recalls of Kyoto, “and it’s absolutely beautiful.”

Pugach continues: “There was no high-level discussion at all of whether to use the bomb. The only issues ever raised at senior levels were civilian causalities and the weather.” (Ironically, although the Japanese islands were believed to represent a target that, unlike in Germany, spared American lives, a group of American POWs were in Hiroshima and died from the U.S. attack.)

Some scientists did urge the government not to use the bomb, but their pleas were prevented from reaching Truman’s ears.

Finding a suitable site was particularly difficult because American bombers had already attacked most Japanese cities, including the firebombing of Tokyo that killed 100,000 civilians.

The bomb-building endeavor, codenamed Manhattan Project, was approved by President Roosevelt for use against Germany, which was known to have its own bomb project. During World War II, however, Adolf Hitler lost interest in the bomb, never having understood its massive military potential. After D-Day, Allied troops were so closely engaged with German forces that using the bomb in Europe became problematical. And finally, Germany surrendered in May 1945 before the bomb was ready to be used.

Yet a vast expenditure of scientific talent, effort and money had gone into building the bomb. The project, Pugach says, had developed a momentum all its own. That momentum required that the project be brought to completion. And then the bomb had to be used because it existed. The rationale that use of the bomb saved the lives of GIs who would have had to invade Japan’s heavily defended main islands seems to have been voiced only after the fact.

In other words, we built the bomb because we could, and used it because we had it.

The Stimson-Marshall memo said the bomb would be ready for use by Aug. 3, 1945. When the bomb was tested at Trinity site in New Mexico in July, Truman received the news on a ship heading to a summit meeting with Stalin in Germany. At the summit, Truman was preoccupied with ending the meeting by Aug. 2 so he would not have to tell Stalin about the bomb. Paradoxically, through his spies at Los Alamos, Stalin knew everything; he didn’t have to rely on Truman.

Dropping the bomb, in Pugach’s view, actually did not require a presidential action. “The decision to use the bomb was essentially on automatic pilot….They wanted to see the fruits of their labor. They really wanted to see it succeed. They wanted to build it…It was a great achievement. Only an exceptional figure in the White House with strength and vision could have stopped the bomb.”

This, in Pugach’s opinion, was not Harry Truman, although he respects the politician who rose from organized-crime-dominated, parochial Missouri to become one of the more successful presidents. Nowadays, Pugach, whose published work focuses on foreign policy and China, performs a one-man show impersonating President Truman, the man history has held responsible for the first use of the atom bomb.

August 05, 2013