In tiny Hanksville, Utah—little more than a crossroads with a gas station, a convenience store, a couple of shabby motels, a few houses—we visited the local Bureau of Land Management office for instructions to Horseshoe Canyon. The man behind the desk seemed surprised to see us. He pointed out the 30-mile drive on a tired map, said we would come upon an old barrel by the side of the road and that would be our indication to turn. From there it would be several more miles of dirt track to the trailhead, which has a pit toilet, and we’d probably see a few other cars.

It was a brilliant early spring day: fierce blue sky and desert light glancing off canyon walls. We locked up the car and set out. The first part of the 7-mile trail descends 600 feet over switchback slickrock, our way occasionally signaled by a cairn. Soon we were at the canyon floor, trudging through the thick sand of a dry riverbed. A couple of plump Chukars strutted out from behind some brush. Horseshoe is a detached part of Canyonlands, its much better-known and more frequently-visited “other half” far to the east. Few hikers, maybe only somewhere between a dozen and twenty a day, drive to Hanksville to explore this remote canyon and its extraordinary pictographs.

But Horseshoe, or Barrier Canyon as it is sometimes called, has its history. Fossilized dinosaur tracks can be seen in the slickrock near an old water tank. Outlaws like Butch Cassidy made use of Horseshoe in the late 1880s, taking refuge in the confusing network of adjacent canyons. Later, in the early 1900s, ranchers built several stock trails into the canyon so cows and sheep could reach water and feed at the bottom. Eventually, the ranchers constructed a pumping operation to fill water tanks on the canyon rim. Many of these modifications are still visible. Prospectors explored the area in the mid-1900s, improving many stock trails to accommodate vehicles and drill rigs. Though they searched the rock layers for oil and other minerals, no successful wells or mines were ever established around Horseshoe. After being added to Canyonlands National Park in 1971, grazing and mineral exploration was discontinued.

We were interested in a history generally referred to as “prehistory,” many thousands of years before the written record. Exactly how many years is still up for discussion. In the 1970s the rock art expert Polly Schaafsma dated the pictographs we have come to see to between 500 BC and 500 AD, or roughly 2,000 years ago. Others make a narrower reference, to the Late Archaic period, from 200 BC to 500 AD. Still others say they are much older, and subsequent discovery seems to push them back in time. Artifacts recovered from sites in this area date as early as 9000-7000 BC, when Paleoindians hunted megafauna like mastodons and mammoths across the southwest.

These pictographs were painted by nomadic pre-Freemont peoples, who passed through but left no evidence of having settled at the mural sites. They thus appear as works of public art rather than interior decoration. Archaic clay figurines that closely resemble the pictographs in style have been found about nine miles away. Since these have been positively dated to around 4700 BC, it is possible that the Great Gallery was painted 7,000 or even 10,000 years ago.

So, 2,000 years, 7,000 years, 10,000 years. We don’t know. In truth, what we can imagine about the people who left these images is greater than what we can back up with solid evidence. There are so many conflicting studies, revisions based on new information obtained from one discipline to another, and we must always be wary of our preconceived cultural notions.

The artists worked hard to acquire and prepare the mineral dust and binder they used to apply color to the rock. They abraded the surfaces that would receive their paintings. The larger-than-life-size figures show vivid artistry and creative voice. These people needed to draw these abstract, humanoid, and animal figures. They had a purpose in depicting hunting scenes and otherworldly beings—perhaps ancestors, perhaps spirits. Their art has been called shamanic, and it may have had a ceremonial or ritual meaning. Beyond question is the fact that they wanted to communicate, and chose what we call art as their medium.

We felt alone in the canyon. We knew a few others preceded us, as we had seen their cars at the trailhead. But silence was our welcome companion as we made our way along one side of the dry riverbed and then the other. After about an hour we spotted a high panel of figures to our left, then a lower panel across the way. Both warranted stops to examine stylized figures of humanoids, birds and animals. Then we continued, easily imagining time had collapsed about our shoulders and that we too inhabited a dimension in which this place was an active painting studio. It is in such places, and at moments like these, where I find it perfectly plausible that time exists as a simultaneous pattern of events and that it is only human consciousness that imbues it with sequence.

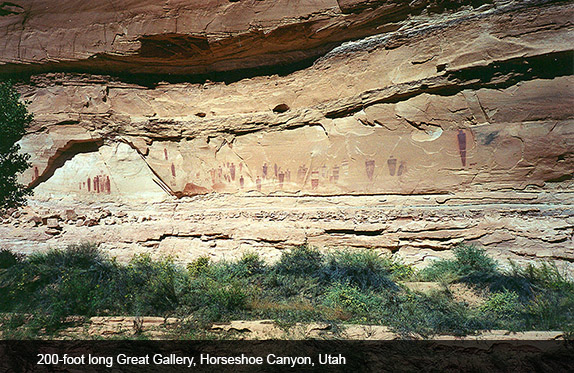

After hiking some three miles, approaching The Great Gallery—Horseshoe Canyon’s signature 200-foot-long panel—an intense energy seemed to thicken the air. As the figures, familiar from photographs, became visible, the impact of the mural hit me. A few other visitors sat quietly on rocks, contemplating the paintings. A troop of some ten or twelve Boy Scouts shared the space; even they seemed to be in awe.

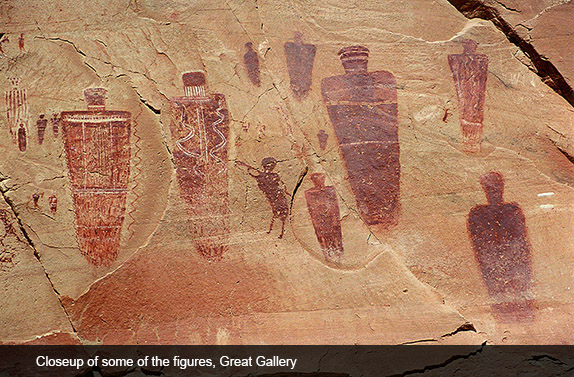

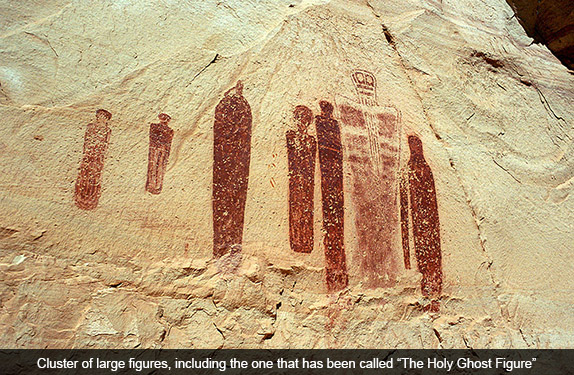

The Great Gallery includes dozens of humanoid figures, often referred to as anthropomorphs, many of them life-sized and one 7-feet tall. Armless, their bodies taper from broad shoulders to narrower lower extremities. Several have skull-like heads; the heads of others are crowned with ornate headdresses. Several of the figures contain wavy designs, rows of white dots, parallel lines, snakes or other figures within their torsos. One, referred to in our overly culturally determined literature as “The Holy Ghost Figure,” was clearly painted with a spatter technique, giving it a sense of movement or perhaps indicating a fur or feather cloak. Some of the large figures have small, mummy-like figures inside them, and there are other mummy-like forms on the wall. Some paint was applied with the artist’s fingers in thicker and thinner layers, and in places the interplay of paint and stone-cutting produces a textural feel.

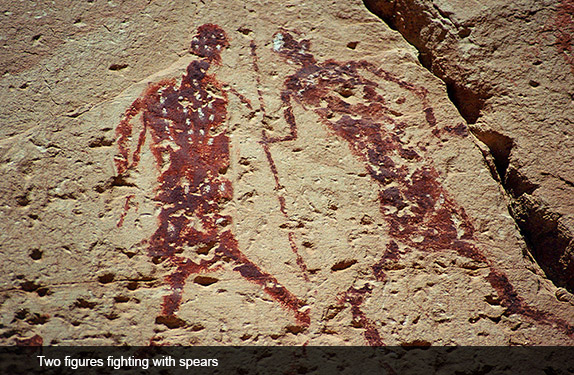

Other images are just as interesting: two human figures engage in a spear fight, an even smaller single figure bears a weapon of some kind, a delicately-painted triangle of mountain sheep run in different directions, and the figure of a large dog seems to be chasing them. At the lowest level on the wall an open mouth or vagina spews a long line of little marks—humans? events?—that issue from it. This last image and the larger figures contain elements of abstraction, or even perhaps record-keeping, contrasting with the medium-sized figures that evidence a realistic sophistication of gesture and movement unusual in most prehistoric painting.

What strikes me, as I remember standing before those 200 feet of archaic art, is that I was looking at a mural. The wall, a fairly shallow and exposed alcove, had been smoothed in preparation to receive the paint. The people—men, women, perhaps even children created some of the smaller images—who painted this wall were creating a magna work of art and/or communication. The word art, because of its contemporary implications, can take us down a slippery slope. We want to say art to convey something transformative, powerful, gripping, with a presence beyond the mundane. At the same time, we want to avoid confining The Great Gallery to our modern-day connotations of art.

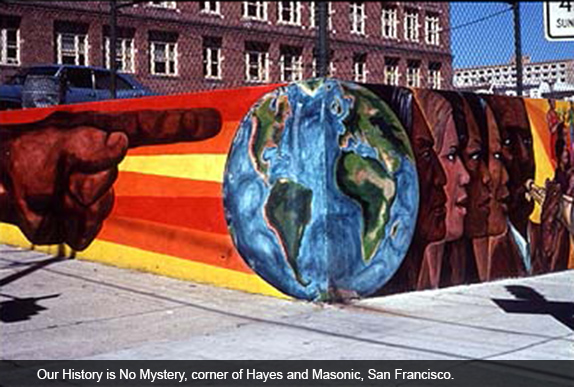

Flash forward thousands of years, but back a few in my life. I am in San Francisco, mid 1980s. I have come to the corner of Hayes Street and Masonic Avenue, to the 320-foot long retaining wall of John Adams Community College. I have taken BART, San Francisco’s subway system, and transferred to a municipal bus. I am west of downtown, near Golden Gate Park. I am here, as I have come periodically over the years, to visit an extraordinary mural painted by close friends. In this era in which artwork is signed, Jane Norling, Miranda Bergman, and Arch Williams are the artists responsible. I have no idea if the ancients who painted The Great Gallery affixed their identities to what they painted, or if they spoke anonymously, for the group.

The San Francisco mural is called “Our History is No Mystery.” The events and people depicted are meant to give a sense of people’s history in San Francisco. Of course I wonder how this explicit representation distances it from, or brings it close, to The Great Gallery. In both cases, I wonder about the artists vis-a-vis their contemporaries. While archaic people painted in Horseshoe Canyon, did others in their community or those simply passing by stop to watch, comment, encourage, or berate? Did the large figures frighten or comfort those who saw them? Were they challenged, or did they take this art in stride?

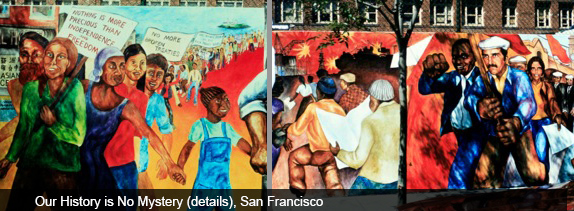

One of the muralists involved in “Our History is No Mystery” says that now, in the era of performance art, she realizes that the act of painting a mural is in fact, performance. She tells me that as they painted this particular mural they were flooded with comments, visitors, offers to help, to model, and more.

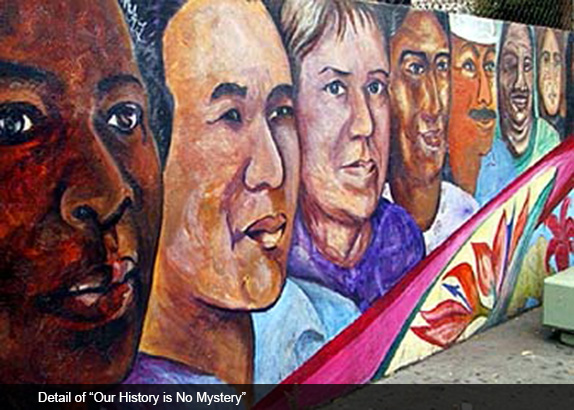

Many people of color are represented on the John Adams wall, reflecting the roles they played in the city’s development. White people often drove by and shouted “where are the white people?”—if they didn’t see themselves in the majority, they didn’t see themselves at all. Their bigotry and fear blinded them to reality and to their place within it. A great deal of research went into planning and designing “Our History is No Mystery,” and photographs of community activists were often the models for their inclusion in the mural.

“Our History is No Mystery” is divided by the street corner that splits it in two. Along one side, a long arm points to the other side, where the action is. This long pointing arm reminds me of the line of dots or small marks that emerge from the mouth or vulva painted in Horseshoe. Both indicate a way in or out: direction, a path.

The San Francisco mural has faded over the years, and it has also been vandalized by one or several people who overlaid the word ugly in white paint not once but twice. Normal restoration has also been necessary from time to time. The artists who painted “Our History is no Mystery” used Politec, a new paint back then developed in Mexico. They power washed the rust-streaked wall, primed it with white house paint, laboriously gridded the mural sketch onto the wall, and then applied the final paint coats in washes, using water as the medium. Later muralists tended to employ paint at full density to eliminate fading.

Thousands of years ago, in Horseshoe Canyon, the muralists had to mix their colors from mineral deposits and plants. They would grind each color to a powder: mineral hematite and red iron oxide for red, limonite for yellow, malachite for green and azurite for blue. Clays stained with other minerals produced various pastel shades. Silica, gypsum, chalk, and calcium carbonate were used for white; charcoal for black. The vehicle and binding agent were combined into a single fluid, to which the ground pigment was added. The binder has disappeared with age, though, so we have never been sure precisely what it was. So, no Politec in ancient times. Each color was a discovery.

As the centuries unfolded, and other indigenous peoples—and finally non-Indians—came upon these rock art panels, some of them also defaced what was there. They have sometimes incised the stone on top of a drawing. In recent times there have been examples of gun-crazy intruders using the images for target practice. In some cases, defacement may have had a ritual meaning. In most, it has been nothing more than thoughtless vandalism.

A mural speaks to us. By its size alone it engulfs, drawing us into its landscape and meaning. We may come away feeling we have participated in its action, indeed as if we embody the identities of its central figures. Painted thousands of years apart, Horseshoe Canyon’s Great Gallery and San Francisco’s “Our History is No Mystery” each put us in touch with the primal forces of an era. A thousand years from now, multi-hued faces on a 20th century wall may seem as enigmatic as the elongated figures in the rock alcove in Utah.

But if we extend our imaginations, we may find profound connections between The Great Gallery panel and “Our History is No Mystery.” Monumental works of art are able to speak not only to, but also for, the people for whom they are created. Think of the Sphinx at Giza, China’s Terracotta Warriors, Picasso’s “Guernica,” and Maya Lin’s Washington DC Vietnam Memorial, to name only a few. When art speaks for us, it allows us to understand who we are. It glorifies and empowers, comforts and explains. By imagining what such creativity meant to the people who made and lived with it, we are able to enter their world in important ways.

July 12, 2013