The Romans called Tunisia their breadbasket. Curtained by the proud shoulders of the Atlas Mountains, the fertile valleys and hillsides of the north are luxuriant with citrus orchards, fig and pomegranate trees, vineyards producing grapes for red, white and rosé, wheat, barley, sugar beets, and almonds that taste like real almonds.

But most of the country is desert, of three distinct types: a salt desert so flat it looks as if it had been planed by a giant trowel, rose beige sand providing a thin cover for the blinding white of salt. Along the lonely highway, a perfectly even ribbon of shallow water glistens. Once this was the bed of an ancient lake. The second is the Sahara sand desert: vast undulating dunes, sometimes naked and then again dotted with sparse but tenacious gray green brush. Its dunes move relentlessly: dramatic hulks of fine sand springing into action at wind’s whim. And windstorms come often. Camels roam, heading for the water they can smell, desert foxes and other mammals run wild, and small rodents and insects leave their crisscross tracks.

Near natural springs, great date palm oases shade the horizon. These are holdings of gold. The trees, with their green frond fans, bring millennial riches. More orderly plantations, called palmeraies, are planted in straight rows. In whichever configuration, each tree—although wind-pollinated in the wilderness—is now more advantageously pollinated by hand, and specialized farmers shimmy up the rough trunk to carry out this task. A single male tree can fertilize one hundred fruit-bearing females. The seed clusters are gathered together on the branch until the tiny green pebbles begin to grow into Deglet Noor, Medjool, and a dozen other varieties. Then the fertilized bundles burst and fruit matures.

The third is the rock desert: gaping wide-open mountains and valleys where wild canyons hide isolated stone or adobe villages. Periodic floods have rendered these villages uninhabitable, devastating abandoned troglodyte berms that have become an extension of the rock itself, melting into its jagged folds. The mouths of their windows and doors cast small dark shadows across such resistant land. Nearby, more modern yet simple homes are painted a blinding white. There is always a mosque, and a school, both carefully tended. A few worn rugs hang over low walls and a coffee can of rhododendron or oleander registers a culture’s yearning for color.

This small cone-shaped country of eleven million inhabitants, wedged between much larger Algeria to the west and Libya to the east, has an 800-mile long Mediterranean coastline. What it offers to the world is agriculture, phosphate, textiles, steel, and some manufacturing. A rich mix of ancient cultures and unique contemporary philosophy imbue it with a particular, sometimes contradictory and often surprising philosophy: the spirit that embraced Muslims and Jews living together in harmony when expelled from Spain in the fifteenth century, and in January 2011 produced the first revolution of the twenty-first.

The tone was set by Habib Bourguiba, Tunisia’s first postcolonial president. At mid twentieth century, when the North African countries began defying colonialist Europe, military men such as Egypt’s Nassar, Libya’s Gadaffi, and Algeria’s Ben Bella shaped their nations’ independence. While these larger North African countries vied for power and influence, Bourguiba understood that his small land would always be militarily weak, and he cultivated other priorities. Education was primary, and during the early years of his mandate 63% of the GNP went to building schools and staffing them with the best teachers study abroad could buy.

In an era of neighboring generals, Bourguiba, a lawyer, paid more attention to social welfare. This meant important changes for women. Even before the new constitution, the Personal Status Code (PSC) was drawn up in 1957. It illegalized polygamy, required the consent of both parties for marriage and raised the minimum age for girls, instituted divorce, and outlawed the burqa and chador—calling them “odious rags.” Bourguiba established full legal and labor equality, and asked that the title “emancipator of women” be inscribed upon his tomb.

Today women outnumber men at all educational levels, Tunisians of both genders earn equal salaries, 46% of the country’s doctors and 58% of its teachers and professors are women, maternity leave is impressive (full pay for the first six months, 75% for the next three, and none for the final three but with job security upon return to work), and abortion is legal during the first trimester. The Tunisian army builds roads, helps harvest crops, and is involved in other communal projects. A year of military service is obligatory for men but optional for women.

Bourguiba is the beloved Father of the nation. He opened the political system to opposition parties. He modernized the country, emphasizing free education and health care for all. And he diverged from most of the other Arab countries by supporting a negotiated settlement between Israel and Palestine. But he also made the mistake so many founding fathers do. He conceived of himself as president for life. When senility overtook him in the mid-1980s, Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali staged a bloodless coup. At first he continued his predecessor’s democratic reforms and investment in economic growth. But he became increasingly autocratic and corrupt. Opposition efforts were crushed. The new president and his family bled a poor country dry.

Phosphate miners organized and tried to rebel in 2008, only to be put down brutally. The press and other media were rigorously controlled. It was against this backdrop that, toward the end of 2010, Tunisians lit the spark that would soon enflame Egypt, Libya, Syria, Bahrain and other countries of the region.

The western press—and at first many within Tunisia as well—spoke about an incident between a street vendor and a policewoman who confiscated his scales because he lacked the proper license. It was said that the vendor immolated himself in protest and this, it was reported, set the country ablaze. International news media, always avid for catchy sound bytes, called it the Jasmine Revolution.

Tunisians prefer to call it the Dignity Revolution. They say its seeds were planted by those phosphate miners several years earlier. When initial public rage around the incident leading to the street vendor’s suicide gained momentum, it was briefly seen as a generating force, and he as a martyr. But when people learned the story behind the vendor and policewoman, they stopped referring to it as the incident that sparked their revolution. It seems that when the woman took the vendor’s scales he made a remark about using her breasts to weigh his goods. Incensed, she slapped him. He doused himself with gasoline, having instructed a few friends to come to his rescue before he could be seriously injured. Somehow, they weren’t quick enough.

Most Tunisians today see the famous vendor as a fool, and one who was disrespectful to women. Both these versions sound a bit too simplistic; who knows where the truth lies? In any case, desperation and will had ripened to the point of rebellion. Young people—adept at cellphone, Facebook, and Twitter communication—took over. Demonstrations were large and well organized. There was very little loss of life, and on January 14, 2011, Ben Ali fled to Saudi Arabia.

Fear was gone, but everything remained to be done.

My partner Barbara and I traveled to Tunisia four months after the Dignity Revolution. We observed ongoing demonstrations, some curfews enforced in areas where struggle had been particularly intense, and occasional police brutality. There were few tourists in the country, almost no one from the United States. Ancient archeological sites were empty. The narrow lanes of villages and medinas and the broad avenues of large cities were clean and orderly: people going about their business with a sense of security and palpable spirit of expectation.

A hotel where we spent several nights near the Libyan border also housed refugee workers in their tan vests with UN stamped in pale blue on the back. Norwegian relief workers from some sort of Christian aid organization were in the dining room at breakfast. Tunisians themselves, poor as they are, were collecting truckloads of food and medicines. One day we saw a caravan of 15,000 tons heading east.

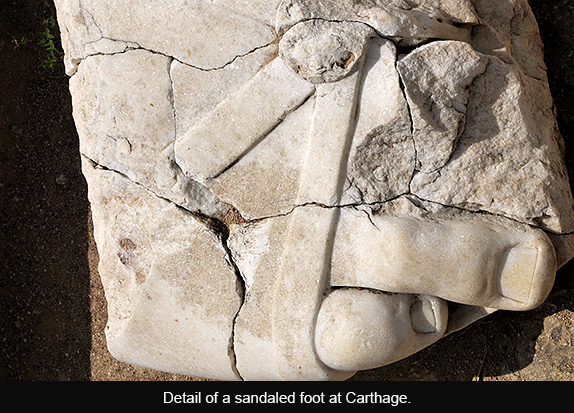

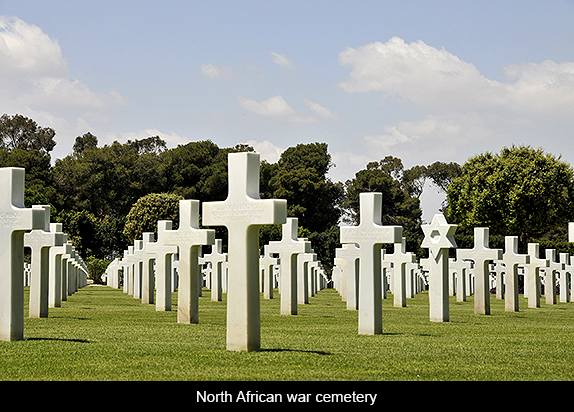

At Tunisia’s great archeological sites—Carthage, Dougga, Kerkoune, Sbeitla—we roamed alone, often for hours, without running into another foreigner. Roman influence dominated, although we also saw the contributions made by Phoenicians, Greeks, Vandals, Byzantines and Sicilians. We were grateful for the rare opportunity to experience these places without crowds, even as we felt for the country’s loss of needed revenue.

Tunisia is a Muslim country. Ninety-nine percent of the population identifies with Islam, and an hour a week of religion is included in the public school curriculum (non-Muslims may opt out of the class). But in some ways separation of church and state seems more respected here than it is these days in the United States. For example Sharia law is not observed. Alcohol is sold (Libyans drive across the border to buy it). At the resorts, discos are hopping throughout the night. If asked, the vast majority of people will say they believe in the Koran, but they seem pragmatic and practical.

In the holy city of Kairouan we visited a mosque, where our guide had arranged for us to meet with a retired imam. The theologian would answer any questions about Islam we might have. Muslims know there are many misconceptions about them in the West, and this would be a chance to hear the truth from an authorized source. The imam greeted us and said we should go around the circle and not be shy. For every answer he consulted a copy of the Koran, which he had in bilingual edition so we could hear the translation. When it was Barbara’s turn, she asked if the imam would mind if she stood, and then addressed him respectfully. I heard several in our group gasp audibly; they must have thought she was going to ask about homosexuality. But this wasn’t what she had in mind. She stated, very simply, that she is an atheist and also a moral person who wants to do good in the world. Her question: “What does the Koran have to say about someone like me?” The imam searched for the appropriate verse. Nonbelievers cannot go to heaven, the Koran says, but Allah himself may decide if such a person may escape hell. Barbara thanked him and sat down.

It was obvious that the imam was intrigued by Barbara’s question, and several minutes later returned to it. Then, as we were leaving, he called her back for a few final words. Looking with kindness into her eyes, he told her she is on a journey, to take her time and persevere.

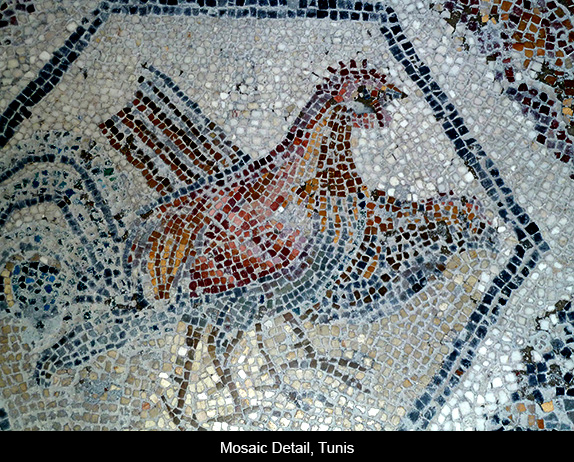

Crafts of different sorts were in evidence throughout the country: fabric, ceramics, leather, silver and gold jewelry, and the ever-present mosaic—with its rich presence from the ancient ruins to modern workshops that produce so much of what decorates many Tunisian homes and public buildings. The Bardo Museum in Tunis is breathtaking, both in its building (a stunning renovation of the 19th century harem of the Beys of Tunis) and contents. There, in the most beautiful natural lighting I have yet to encounter in a museum, walls, floors, and even ceilings are covered in mosaics large and small, many dating back to centuries before our era.

The art of mosaic continues today. We visited a small workshop where a dozen young women were engaged in the craft—in this case following prescribed patterns used in tabletops, trivets, wall pieces and other commercial manifestations. Despite not sharing a language, some of the young women and I joked around. I took pictures. They wanted to see them on the camera’s monitor and to select which they felt I should keep and which erase.

As Lana Asfour writes in Granta The F Word, “One of the most interesting aspects of the Tunisian revolution from a feminist perspective is that many of the women who participated in the protests that brought down Ben Ali are now campaigning to defend rights they’ve already been enjoying for some time, fearing that the post-revolutionary period might bring a surge in popularity for the Islamist party, Al Nahda (‘The Renaissance’), and a swing towards traditionalist ideas about women.”

Not two weeks after the January 14th 2011 victory, on the 29th of that month, the country’s two independent women’s organizations joined the women’s commission of the national trade unions and the Tunisian League for Human Rights in a demonstration to make sure their rights would be protected in the transition and afterward. I’m told that many women marched proudly down Habib Bourguiba Avenue. They carried placards and chanted slogans in support of the revolution and aimed at safeguarding women’s rights. The women had to contend with attacks from ruffians hired by elements of the old ruling party, and at a certain point were forced to disband. Individual women also must argue with men who don’t see the new Tunisia as necessarily including women’s rights.

It wasn’t until I’d been in Tunisia for a week that I realized there are no McDonald’s in the country, the ubiquitous golden arches nowhere to be seen. Coca Cola is sold, though. Tunisia has its own fast foods, most of them liberally saturated with harissa, which is a spicy paste present at every meal. Harissa is made from red chile, garlic, salt, olive oil, coriander, caraway seeds and cumin. There’s no Tunisian Disneyland, either, although in the seaside resort of Hammamet we saw a Carthageland, complete with a larger than life tableaux of Hannibal mounted on his elephant.

Entering the town of Kairouan, the country’s rug-weaving capital, we passed a monument four stories high depicting intricate rugs rendered in mosaics. Entering other towns, equally large monuments advertised their specialties: one giant bowl of bright oranges, another huge ceramic pot. Rug weaving is a Berber specialty, an age-old tradition. In contrast with Egypt, there is no child labor here. Adult women do most of the weaving in their homes, and each family has its traditional designs. Centers seem to use a system similar to the one fast fading from the U.S. American Southwest’s trading posts, whereby looms and yarns are provided and the rugs purchased outright. Such support promotes community and encourages the most authentic work. Examples range from the crudest weaves, with 10,000 to 40,000 threads to the square meter, to the finest silk with a million threads in the same space.

At the beginning of this trip, flying from Paris to Tunis I noticed there would be an hour’s time difference. But wait. It would be an hour earlier in Tunisia, despite that country being one time zone east of France. Shouldn’t it be an hour later? I asked the flight attendant, who explained that France observes daylight savings while Tunisia does not. I sat and thought about that for a while. Wouldn’t this then make it two hours earlier? Or the same time? I went around and around with this but couldn’t make it work. I went to Air France’s inflight magazine and searched for the world map. As I suspected, it included the time zones. Tunisia: to the east of France. No way I could figure it out.

Time itself, the essence of time, seemed to accompany me throughout this trip like a great rubber band, stretching and contracting. With so many out of work, the cafes were filled with men of all ages, sipping tea or drinking beer, gesticulating in a language I don’t know (Arabic or French, sometimes a symbiotic blend), playing cards, occasionally smoking from a hookah or water pipe. Women, as everywhere, walked arm in arm, whispered to one another, carried bundles, shopped, took children to and from school. But their pace seemed slower than in other places I have been. The heat of summer was still a couple of months off. We were told it routinely reaches 120 to 130 Fahrenheit in August and September. In May it hovered around a pleasant 80 degrees.

But the time issue seemed to embrace centuries. The ruins of Carthage, for example, blend almost seamlessly with the present-day busyness of a modern capital. Around the Gulf of Tunis, 3,000 years of civilization—Phoenicians, Romans, Vandals, Muslims—lack the continuity of documented history due to the fact that the Romans, after destroying and before rebuilding the city, did away with important sources. The story of Queen Dido told in Virgil’s Aeneid, may be more about attitude than accuracy. Kerkoune, a 2,300 year old Phoenician ruin with the Mediterranean lapping its low stone walls, is unique in that every house had its own private bath: a time warp if ever there was one.

Time also has a different history in the small village of Testour, in a lovely valley above the Mejerda River. There, the square minaret of the oldest mosque bears the imprint of a clock whose numbers run backwards. As with any modern timepiece, the twelve is at the top. But the one is to its left rather than right, and the rest of the numbers continue counterclockwise around the face.

This minaret, which also displays eight Stars of David, dates to 1609, when Muslims and Jews—expelled from Spain together—settled here. They longed for their Andalusian homeland, and this backward moving clock symbolized that longing. Unfortunately, the clock’s hands are missing, so I had to imagine a movement of time, which may or may not have been mechanically possible.

Most of the hotels where we stayed, if they had Wi-Fi at all, had it only in their lobbies. One morning, very early, I sat in the reception area of one, using my laptop. The night watchman rose from a couch where he had spent the night, stretched and gave me a shy smile. Then he came over to where I was working. “Are you writing to the United States?” he wanted to know. When I told him I was, he asked what time it was there. I explained that mine is a large country, with several different time zones. The concept didn’t seem to register. “But what time is it where you’re writing?” he asked again. “Eleven-thirty last night,” I replied, before realizing how absurd that sounded. “I mean it’s still yesterday where I live.”

The man was incredulous. Clearly he could not conceptualize it being yesterday somewhere in the world when here it was already today. The people of Tunisia, who through largely peaceful protest have just changed the course of their history, must play a new game with time. How long is too long to wait for change? How will memory and political expediency deal with past abuses?

June 20, 2014