In her book, The Dread Road, the great Midwest radical writer Meridel LeSueur (1900-1996), wrote:

I used to take tranquilizers going the dread road north through the injured earth, through the oblique horizontal valley of the massacres, the mining hills where our fathers slaved in the dark for hardly enough to feed their children . . . filled with ghosts, veering the bus in sorcerers’ winds. I took the pills before we got to Trinidad, toward Ludlow flying, penetrating the distance . . . where Louis Tikas was riddled with 85 bullets fired point-blank as he tried to protect the children underground in the cave below the tent. You can lift a cellarlike door now by the monument and you can descend into that pit and hear the cries of the children.

After Meridel’s death, a group of Albuquerque poets and writers got together one night at The Living Batch, the wonderful literary bookstore that has been gone now all these many years. Pat Smith had baked a special cake, in the shape of the small suitcase that figures prominently in LeSueur’s book. Joy Harjo played her alto saxophone. John Crawford, editor of West End Press, had organized the event. I cannot remember everyone who took part that night, but I know we read the book straight through—in tribute to Meridel and to Ludlow. It was a night to remember.

I had always wanted to visit the site of the Ludlow massacre, one of the worst repressive actions against working people in the history of our country. Driving on I-25 from or to anywhere in central Colorado, I had often noticed the small brown historic sight marker on the side of the highway. It doesn’t tell you how far off road the Memorial is, though, and we never made the detour. Recently, coming back down to Albuquerque from Boulder and just a dozen or so miles before the small town of Trinidad, we decided this was the moment for a visit.

I had always wanted to visit the site of the Ludlow massacre, one of the worst repressive actions against working people in the history of our country. Driving on I-25 from or to anywhere in central Colorado, I had often noticed the small brown historic sight marker on the side of the highway. It doesn’t tell you how far off road the Memorial is, though, and we never made the detour. Recently, coming back down to Albuquerque from Boulder and just a dozen or so miles before the small town of Trinidad, we decided this was the moment for a visit.

The memorial site is in fact less than a mile to the west. You drive across a prairie that probably doesn’t look that different from what it looked like in 1914, stripes of corrugated tan rock visible in the surrounding hills. A modest sign erected by the United Mineworkers of America announces the “Ludlow Memorial Monument,” and then there it is: a tall granite marker of classic design with a plaque and three figures: the miner, his wife and child. A metal fence surrounds the monument, its rungs painted red, white and blue. It was locked.

Although the United Mineworkers were never recognized by the mining company of Colorado Fuel & Iron, the union eventually bought the site in 1916. Two years later they erected the monument to commemorate those who died. In May 2003 unknown vandals damaged the stone tribute, necessitating the protective fence.

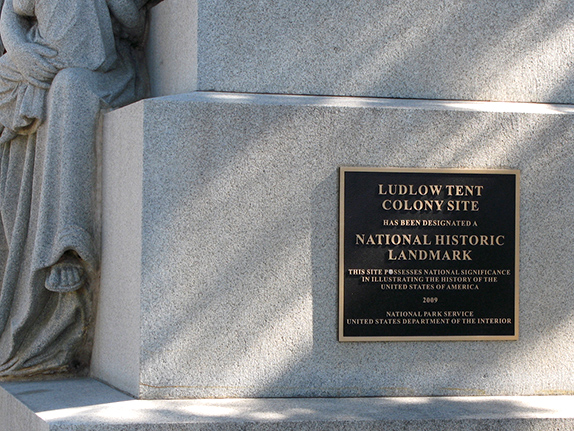

The monument we see today was unveiled on June 5, 2005; the statues’ faces were slightly altered in the process of repair. On January 16, 2009, the whole Ludlow Tent Colony site was declared a US National Historic Landmark. The citation describes the Ludlow Massacre as “a pivotal event in American history,” and notes that the site is the first of its kind to be investigated by archeologists. Interestingly, the archeological data substantiates information preserved all these years by the survivors of this horrendous mining repression.

Historians, writers, and singer/songwriters have memorialized the Ludlow struggle and tragedy. Howard Zinn wrote his Masters thesis and several book chapters on Ludlow. Former Senator and Democratic presidential nominee George McGovern wrote his doctoral dissertation on the subject (this was later published in book form as The Great Coalfield War). American folksinger Woody Guthrie wrote “Ludlow Massacre” and Irish musician Andy Irvine produced “The Monument” (“Lest We Forget”). Upton Sinclair’s King Coal is based on the origin and aftermath of the Ludlow Massacre. Thomas Pynchon’s 2006 novel, Against the Day, also contains a chapter on the event. The last Ludlow survivor, Mary Benich-McCleary, died at the age of 94 in June 2007. She was 18 months old when the massacre was perpetrated.

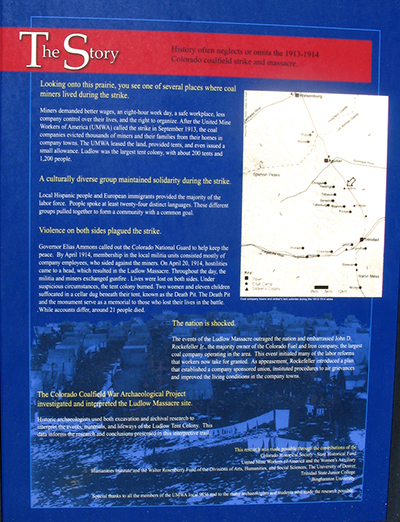

So what happened at Ludlow?

This was coalmining country, with all that implied at the time in terms of a makeshift colony where several thousand men, women and children lived in a couple hundred tents. Conditions were rudimentary and unsafe. The miners labored long hours in dangerous circumstances. Salaries were meager, medical attention rudimentary, and benefits a dream not yet dreamed.

In 1912, the death rate in Colorado’s mines was 7.0555 per 1,000 employees. Two years later, the United States House Committee on Mines and Mining reported that “Colorado has good mining laws [ . . .] that ought to afford protection to the miners as to safety in the mine if they were enforced, yet in this State the percentage of fatalities is larger than any other, showing there is undoubtedly something wrong in reference to the management of its coal mines.”

Miners were paid by tonnage of coal produced, but the so-called “dead work,” including shoring up unstable roofs, was rarely remunerated. Explosions were frequent, and mine roofs often collapsed. In the early years of the twentieth century, frustrated by these unsafe working conditions, miners began to turn toward unionism. Nationwide, the mines that were organized had forty percent fewer fatalities than their nonunion counterparts.

Colorado Fuel and Iron was the largest coal operator in the western United States at the time, and also one of the country’s most powerful corporations. CF&I was purchased by John D. Rockefeller Jr. in 1902. He managed his operations from his office in New York City. Far from his eyes or concern, the coal miners at Ludlow began to organize. In 1913, the United Mine Workers of America presented a list of seven demands on behalf of the Ludlow workers:

1.Recognition of the union as a bargaining agent

2.An increase in tonnage rates (equivalent to a 10% wage increase)

3.Enforcement of the eight-hour workday law

4.Payment for “dead work (laying track, timbering, handling impurities, etc.)

5.Weight-check men elected by the workers (to keep company weight men honest)

6.The right to use any store, and choose their boarding houses and doctors

7.Strict enforcement of Colorado’s laws (such as mine safety rules, abolition of scrip, etc.) and an end to the company guard system.

All the major coal companies rejected these demands, and in September 1913 the UMWA called a strike. Those who went out on strike were promptly evicted from their company homes and moved into tent villages prepared by the union. CF&I hired the Baldwin-Felts Detective Agency to harass the striking workers and protect the scabs they brought in to continue their mining operation. On October 28th, as violence mounted, Colorado governor Elias M. Ammons called in the Colorado National Guard. The Guard’s sympathies lay with management, so their role was far from one of real protection. This may sound familiar to Albuquerque residents, currently trying to get our police department to protect us rather than engage in unchecked acts of violence.

Things exploded on April 20th, the day after the Orthodox Easter had been celebrated at the tent colony. Guardsmen provoked a crisis, causing camp leader Louis Tikas to meet with a local militia commander at the Ludlow village train station half a mile from the colony. A fight broke out and raged for an entire day. Tikas and others were shot in the back. Four women and eleven children hid in a pit beneath one tent, and were trapped when the tent was set on fire. Two of the women and all the children suffocated. It is not known exactly how many died at Ludlow, but at least a dozen deaths were documented.

One hundred years later, almost to the day, mining companies in the United States and throughout the world still extract coal through the unsafe exploitation of human labor in dangerous conditions. Mines still collapse, trapping hundreds of men inside. A few dramatic rescues grab headlines, while the vast majority of such accidents end in the deaths of everyone caught below ground. Fracking will undoubtedly also produce its stories of greed and exploitation. In recent years, exploding oil rigs have written vivid stories as well. And nuclear plants and waste storage sites add their own versions of danger.

Until sustainable energy takes the place of, or alleviates, the predominance of nonrenewable fuel sources, we will continue to rage against inappropriate working conditions, complain about company shortcuts that lead to slow death and mourn the accidents that produce dramatic loss. The Ludlow Massacre Memorial is a moving tribute to brave miners and their families who struggled, fought, and died a century ago. In my mind, it honors as well all those victims of commercial greed who are forced to labor in conditions guaranteed to make them and their children ill, or simply kill them outright.

Like Meridel LeSueur, at Ludlow I heard the cries of the children.

(Lead photo of monument front by mkwalker, all other photos by Margaret Randall)

July 03, 2014