Editor's note: This piece was originally published in First Laugh: Essays 2000-2009, University of Nebraska Press, 2011 under the title, Crystal's Gift.

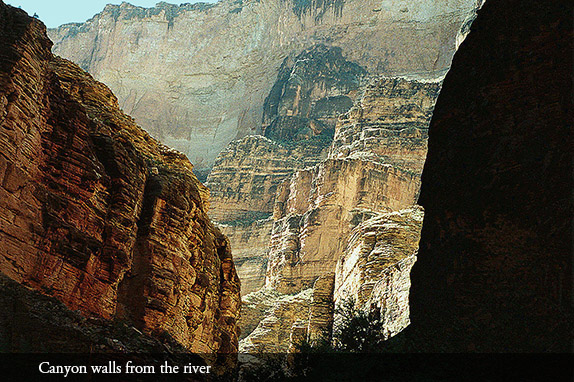

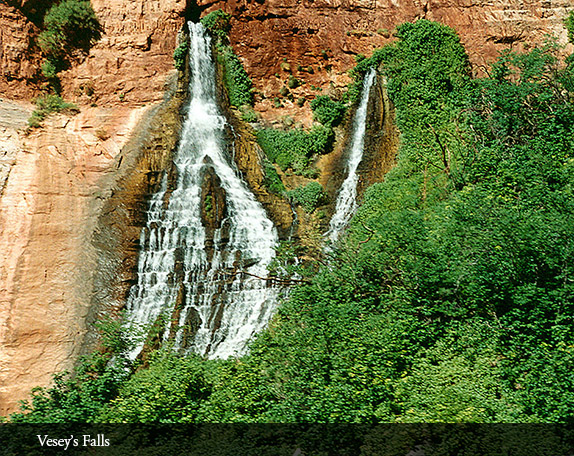

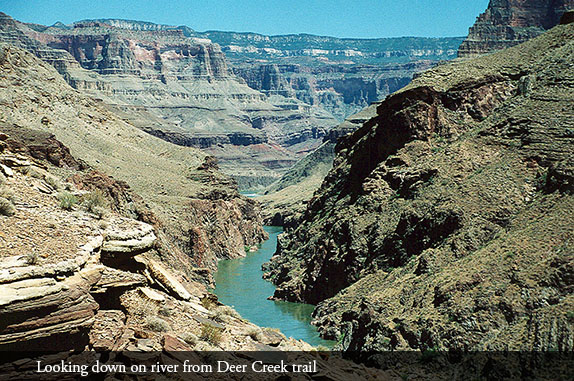

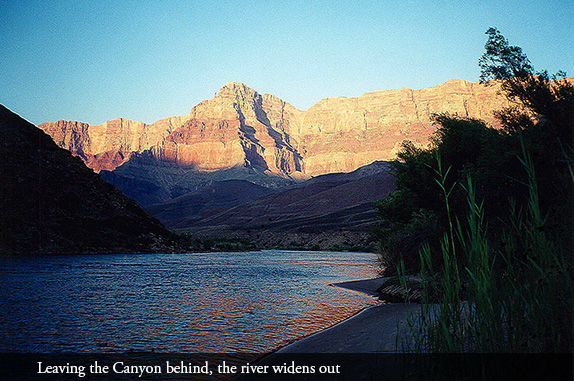

Imagine walls of massive rock, where two hundred fifty million years disappear without a trace into something called The Great Unconformity. Think of a river named Colorado, for the deep brown-red of her waters before men built a dam to harness her course. Learn that this section of river now issues from beneath Glen Canyon Dam, keeping a steady forty-eight degrees in contrast with July’s hundred-plus-degree heat.

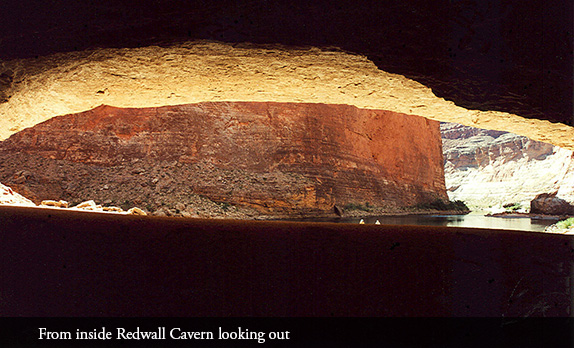

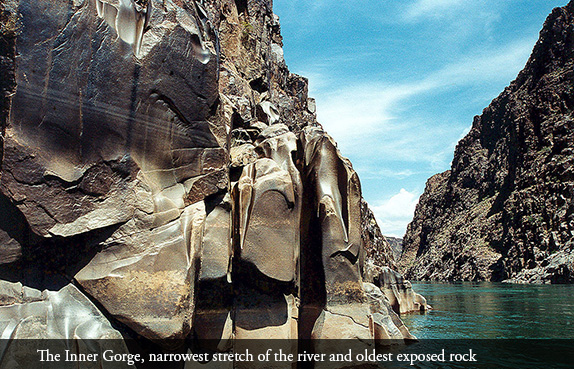

Two hundred eighty-seven miles of river flow between these canyon walls. Here light moves across shadow, shadow cuts through light. Billions of years of polished black schist are infused with stripes of pink granite, and these glisten richly in the midday sun. Grand Canyon, where the Colorado parts its series of inner gorges, is a geological event that touches the most intimate places of memory.

This is a story about the women who row this river in a world of men. Nine women in particular, who rowed in the summer of 1997, for twenty passengers—also women. I am one of the latter. We have come from different places with varying expectations, some seeking challenge, others quiet retreat. Many of us are long-time friends; others meet for the first time in Flagstaff the night before we put onto the water. We are writers, artists, an anthropologist, a math professor, a filmmaker, a steel worker turned book binder, a special education teacher, nurses, an investment counselor, a builder of houses, massage therapists, a midwife, a muralist and graphics designer. We range in age from our twenties to our sixties.

The boatwomen are our guides. They will reveal the river’s mysteries, offering them in manageable pieces, explaining—but never too much or too fast. From their own experience, they will introduce us to the river, and the river to our shy or awestruck tracks.

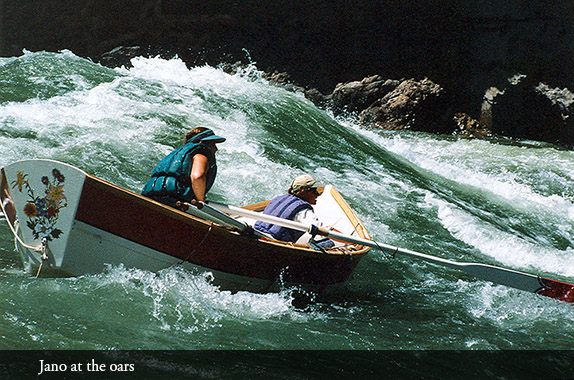

Our trip leader, Jano, is baptizing her own dory on this trip. In 1997 it is still hard for women to get certified, to accumulate enough trips so they may become licensed to carry passengers. Women row baggage rafts for years before they get to row a boat. Men often show up at one of the companies and are hired on the spot. Once they do obtain their licenses, most boatwomen row rafts; some operate motor rigs. Few row dories, fewer still dories they build themselves.

Jano does just that. She worked on her fifteen-foot rig weekend after weekend, driving in to the company warehouse in Flagstaff from her teaching job on the Navajo reservation. In the construction process, this thirty-one-year-old river guide, writer and teacher learned to shape and lay the fiberglass decks, mold gunwales of pale ash, attach hardware for the hatch covers and master the math that brought it all together. In this community dories are traditionally named after places damaged or destroyed by man. Jano’s is the Animas, after the Animas River in southern Colorado, now ravaged by industry and development.

At almost fifty, Ote is our oldest woman at the oars. She will be rowing Dark Canyon, in its classic design a sister to Animas. Ote is tall and lithe, sinewy of body, weathered of face. At a critical point along our way, she will give me an image I will not lose: her determination standing and straining as she manages to bring her dory back upriver and in through a fierce eddy line just below the worst of Crystal Rapid.

At mile Ninety-eight-and-a-half Crystal is the Colorado’s most technically difficult rapid—rated a ten plus on the scale of one to ten. A huge hole drops just below its glassy tongue, giant waves crash in every direction, and a treacherous rock garden separates its upper and lower sections. In her capacity as trip leader, Jano decides Crystal is the only one of this river’s forty-seven major rapids we passengers will not be permitted to run.

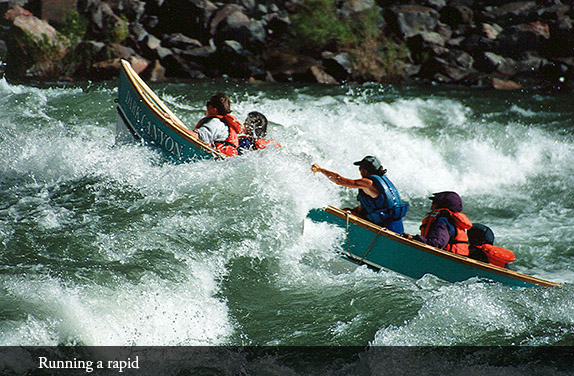

Our guides will take it on in twos, each woman bailing for her sister and then running back along the shore to repeat the process with another boat. We will struggle on foot across the debris field which borders the rapid. The boatwomen tell us there are two eddies, and they will try to make it into the first, thereby avoiding our having to extend an already strenuous hike further down river to the second.

Before attempting this feat, they tie up their boats, climb to a rise of rock and scout what they are about to navigate. One collects dry branches which another tosses into the current, to see which way they go. Then they are ready. Quick hugs and into the boats. We start our trek. One after another, each spot of color approaches the rapid: toy-like images far below us in the thunderous river—now visible, now disappearing beneath huge surges of spray. It is all about entering correctly. As if suspended, each dory floats for a moment on the swelling tongue, then plunges into the current.

Only Ote finds herself in position to try for the first eddy. She knows how important it will be for at least one boat to be there to pick up the more physically challenged among us. In her mind failure is not an option. And—every leg and arm muscle taut with the effort—she makes it through. No one else comes close.

But I am going too fast. Ote’s accomplishment is still days ahead of us, down river. As we put onto the water at Lee’s Ferry, this moment and others of equal drama are yet to come. Now the women finish loading their boats. Elena, who is a public health nurse off-season, will row the Phantom. Mary—graphics designer and artist—laughs as she runs her rough fingers over the cracked gray decks of the Mille Crag Bend.

Although she did not build it, the Mille Crag also belongs to Mary. Its ownership fulfills a long-held dream. No more than a week before our trip the phone call came from Martin Litton, writer, conservationist, founder of Grand Canyon Dories and grand old man of the Colorado. “You want the Mille Crag?” he asked her, referring to the old Briggs boat stored unused for the past eight years up at his place in Hurricane. “Yes I do,” Mary managed to sputter, caught totally by surprise. On a number of occasions she had asked her friend to sell her this boat. Now: “How much to you want for her?” “What, you rich or something?” the man’s gruff laugh accompanied his revelation of the gift.

The Ticaboo is being rowed by Cindell: small, wiry, a high school physical education teacher from Tucson. This is Cindell’s first time rowing passengers the length of the Colorado through Grand Canyon. She has passed up a chance to make a trip with her husband, also a boatman, to participate in this all-female adventure. Our first morning out, one of the other boat women suggests a stop at a particular beach. Hanging on the branch of a tree, some two hundred yards from shore, Cindell discovers a zip-lock bag containing a lovely turquoise ring: a surprise gift from the man she loves.

Now the women finish packing their boats. Stephanie and Nicole each command a large yellow rubber baggage raft; their helpers are Jenna and Denise. We make our first of many human chains to help load dry bags, sleep kits, and other paraphernalia for sixteen days of life along the river’s banks. Everything carried in must come out.

Our life jackets are being fitted now: low and snug. They bear the names of local animals or places. Each of us will remember “Pallid Bat” or “Canyon Wren” or “Nankoweap,” so these life-saving devices may remain with us and always fit as they should. After Jano rounds us up for final introductions and a few last-minute safety tips, we group up four to a dory and put into the green water.

The river has been running relatively high at 27,000 cubic feet per second (cfs), issuing from under the dam at a volume and speed that washes some of her rapids out and makes others larger, less predictable. The engineering project was authorized by Congress in 1956 and completed in 1963. Beyond erasing forever magnificent Glen Canyon, it has changed the Colorado from the raging current rowed by Powell in 1869 to the tamer but still unpredictable river it is today.

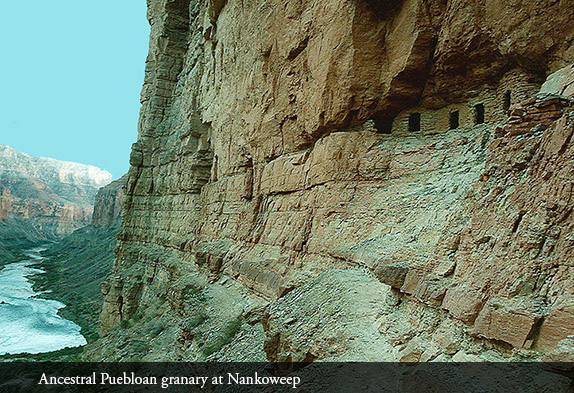

We are finally on our way. And now the stories begin—about rock strata, sediment, water and wind: how the Canyon came to be. Stories of the ancient Basketmakers who first inhabited this place, of the Ancestral Puebloans and more recent Hualapai, Havasupai, Hopi, Paiute, and Diné (Navajo). Stories about Powell, Stanton, and others among the early white explorers. The men who first ran this river—in scows, motor craft of various kinds, eventually rafts and dories. And about the very few women linked to Canyon history.

The first were the old-timers’ wives and daughters. Although the legends and books do not focus on them, many made enormous sacrifices for the river and shared fully in early explorations. Then came a group of Hollywood models. Requisites were beauty and (just as absurd) an ability to swim; they were hired by the first companies to add glamour to the river’s commercialization. Finally, several generations of boatwomen made their way onto the Colorado.

Georgie White was the first, a generation with a single name. For forty years she was the only woman of Grand Canyon river legend, until male resistance began to crumble before female skill—and will. Then came Marilyn, Liz, Suzanne, Connie, and Ellen: the second generation of Colorado River women. Today we are traveling with women of the third generation. They are still pioneers.

“Was that a rapid?” “No, just a riffle.” Nervous or relieved laughter can be heard from boat to boat. “How long have you been rowing? Was it hard to break into the man’s world of dories?” Our questions come, uncertain at first, the boatwomen’s answers also tentative, feeling us out.

Then, as the days unfold, the old stories emerge. There is the geology and the botany of Grand Canyon, how the same huge barrel cactus we saw on yesterday’s hike can be seen in a hundred-year-old photograph made on the Stanton Expedition of 1892. There are tales of the Big-horn Sheep, the lizards and snakes and hawks and wrens. Our guides are experienced experts in all these fields.

And there are the human stories: what really happened to the three men on Powell’s first expedition who gave up on the endeavor and walked out at what we now call Separation Canyon? Were they murdered by Paiute Indians as the plaque in their honor claims? Did they die of thirst and hunger somewhere along the nonexistent trails? Or were they shot by Mormons who believed them federal agents, a version that has gained credibility with the recent surfacing of a series of old letters?

Then there were Glen and Bessie Hyde, honeymooners who went down river in a wooden scow in 1928. The few who saw them along the way said the trip was his idea; she was clearly unhappy, being prodded along by her publicity-seeking husband. Why was their boat discovered intact? Why were no bodies ever found?

A boatman on my first river trip, back in 1995, told me that on another trip he and his group were sitting in a circle after dinner one night on one of the Colorado’s quiet beaches. He was telling the Bessie and Glen Hyde story. Suddenly a woman in her eighties stood and walked to the center of the circle. “I’m Bessie Hyde,” she announced.

The age seemed right, some of the details too. The woman was later questioned by reporters, but proved unwilling to reveal what had happened to Glen or how she had walked out of Grand Canyon. Mute testimony—if true—to what can happen when a man tries to force a woman to do something against her will.

There are plenty of stories about Georgie White, or Georgie Clark as she was later known. In the mid-fifties she devised a way of linking three big pontoon motor rafts—Georgie’s G-rigs they were called—in order to take large numbers of people down river at a price they could afford. She was the first woman to run the Colorado commercially, and made the experience accessible to thousands.

But on our trip the stories that most vividly resonate within me are the ones about our own boatwomen, their ordinary and extraordinary lives. These stories are harder to come by; the women tend to talk little about their accomplishments.

Each woman who has wanted to take a dory through Grand Canyon has had to row baggage or cook for these trips an average of six years before being entrusted with a boat and passengers. Ote started rowing in 1976; Elena, Mary and Jano in the eighties. Cindell has rowed baggage for years; this is her first commercial dory experience.

Can women row dories? In this tradition-bound community the question once challenged women as well as men. For years the answer was not the off-hand “of course” that it is today. But dory people now agree that women make up in finesse what they may lack in absolute strength. “We learn to read the water really well. Each of us develops a style that works with our body. And then we’ve had all those years of practice” Mary laughs.

None of the many details of their lives, though, reflects what makes these women seem a breed apart. Rather, it is the solidity of their underlying self-confidence, the sense they embody that if you love something you just naturally go after it. And if you go after it you will do it well. No doubt in these muscular arms as they guide their boats through the water. No ostentation, no bravado or risk for risk’s sake.

Now all but one of the baggage rafts have run Crystal. Two dories have sustained severe rock damage and will be mended by their boatwomen when we reach an accessible beach. All that remains is for that last raft to come through. Suddenly there it is. And then those of us watching from the rocky shore look helplessly as it flips like a slip of paper in slow motion, coming down bottom-up upon the waves.

We can see Stephanie’s and Nicole’s bodies. One woman is clinging to the edge of the raft, the other rushes by some hundred feet in front. They are being carried through the churning rapid at more miles per hour than any of us wants to contemplate. The raft, now a lump of gray instead of its familiar yellow, careens among the rocks.

Ote’s dory still bobs alone in the first of Crystal’s eddies. We shout down to the boatwomen who have tied theirs up in the second eddy far below: “A flip,” we yell, “there’s been a flip!” “Shit,” I later learn is Jano’s first response, “I’ve got to get those women.”

With two passengers sitting in Animas she wastes no time pulling into the current. She positions herself as the two terrified members of her crew come racing down and, one after the other, pulls them into the dory. Then she manages to grab the overturned raft and bump it to shore.

But this is only the most important part of this rescue. When a dory flips it is easy to right. Two or three moderately strong women standing on the upturned bottom, arching their backs and pulling on the flip line, can accomplish the task. We have been coached several times in this, given explicit training in how to proceed should our dory succumb to an angry wave.

When a baggage raft goes over it’s a different story. The fully-loaded hulk of rubber is heavy and awkward and extremely difficult to return to its upright position. Now the gray mass sits defiant, all our lashed-on gear hidden beneath it in the water.

More quickly than any of us could have imagined possible we have brought the raft alongside a rocky part of the shore. Not really a beach but we had no choice. A few of us stand in the numbing water to keep the wooden boats from crashing against the sharp obstructions or ourselves. Quickly, deftly, the boatwomen rig a series of ropes and pulleys; a rise of jagged rock affords a certain angle of maneuverability.

With more time to struggle with the rigging, twenty-some-odd women would have been enough. But a passing raft trip has stopped to offer assistance. With their power and ours we manage to right the monster. Everything tied on is still there. The bags are wet but none the worse for their long soak, and their contents are safe and mostly dry. Relieved we make our way a short distance further down river where we will lunch as the women whose dories have been damaged pull them ashore and plug their holes.

Later that evening I ask Jano: “On a mixed trip what would this day have been like?” “The men would have taken over,” she tells me, smiling but with an edge of seriousness in her eyes. “The work would have gotten done of course. But we would have been pushed aside. That’s the way it is. When there are men around, the women just don’t get a chance to deal with the problems that arise.”

But neither is this the end of the incident. Women have our own ways of handling mishap and fear. Jano gathers her crew on a secluded part of the beach, giving the two women who flipped their needed opportunity to debrief, vent, cry, be held. She makes sure they understand it was not their fault. In Grand Canyon boats flip every day. And Crystal is certainly one of the places where that happens.

A quality these boatwomen share is their deep devotion to passing it on. They love teaching the younger guides, and aspire that each passenger not only experience Grand Canyon to its fullest but come to know her own potential: previously unclaimed strengths, a trust in her body, new powers of observation, the ability to make connections in this harsh desert terrain.

“The one piece of advice I can give you is: go slow.” That’s Jano in Flagstaff the night before we depart. “Go slow. Look. Listen. Pay attention.”

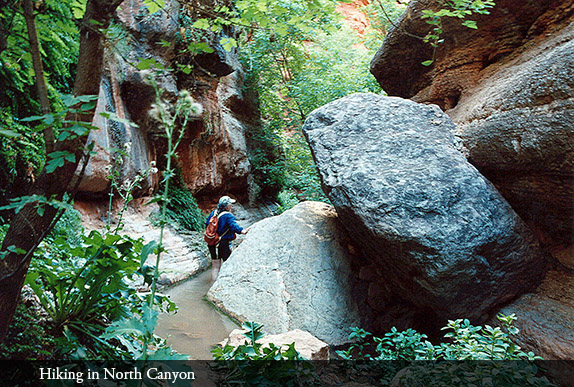

Like precious gifts these women give us the unequaled beauty of a magical fern-covered slot or the way out of a lifetime of vertigo. They do not offer these experiences lightly but teach us how to acquire them for ourselves. It is not by pushing or extolling that they instruct, but by watching, listening, and being present—always—to offer a hand or point out a foot- or finger-hold.

Gradually we passengers find we need less, appreciate more. Dropping into a slot canyon was a challenge we didn’t think we’d meet, but did. Scaling a difficult stretch of rock another. We delight in the little bats that circle above us as we sleep, look closely at the Ringtail Cat tracks appearing at first light around our camp, marvel at the legions of tiny frogs.

The river becomes our companion, friend, source. We drink its filtered water, urinate in its rapidly renovating current, wash clothes in its eddies, cool ourselves or bathe in its shocking temperature, feel its caress against our skin.

In a little more than two weeks, the boatwomen have made it their business to see, really see, each one of us. They have learned our physical and emotional limits and worked to help us stretch—unobtrusively, so that we do not know we are being worked with except perhaps in retrospect.

Before this journey one or another of us might have said we were running the Colorado for the excitement of the rapids or the beauty of the Canyon, for the opportunity to spend sixteen days beside walls of rock that are at once ethereal and massive, translucent and imposing, gold orange red and deep violet in moonlight or brilliant sun. We might have explained that we wanted to get away or be in nature or commune with four billion years of life.

What we didn’t know was that we would be given the gift of ourselves. This is what these boatwomen offer, each from her unique experience. These women who regularly spend time away from lovers and well-paid work to transport people to the center of the earth—where, if we have looked and listened, we will have found the greatest gift of all: a new belief in our untapped capacity to be and do.

July 26, 2013