There was a time when Lincoln County was the largest in the United States. Its vast territory occupied a fourth of New Mexico. Early inhabitants were the Mescalero Apache. Hispanics came into the area from Mexico, indistinguishable despite the troublesome border established by the Gadsden Purchase Treaty in 1853-54. Then bands of European immigrants—mostly Irish and Scotch—established large land holdings, ran cattle, and devised schemes by which they hoped to out-maneuver rival bands and make fortunes through a variety of entrepreneurial monopolies. Fueled by the deadly combination of 95% whiskey, six-shooters, and general lawlessness, they went after one another until their activity exploded into the five-day Lincoln County War of 1878. Greed and a lust for power, not unlike similar scenes today.

Following the Civil War, thousands had made their way west to Texas and New Mexico. They settled where there was water, good grazing, or mineral-rich land free for the taking promised profitable mining. In Lincoln County, Horrell, Murphy, Dolan, McSween, Huff, Tunstell, and Peppin are some of the surnames that come down to us. Nearby Fort Stanton was re-garrisoned, and the Apaches, who had once roamed freely throughout the region had been rounded up and largely controlled. A small community called Las Placitas del Río Bonito was renamed Lincoln in 1869, and the village was the scene of the Lincoln County War’s final shootout. The name most remembered from this event is that of Billy the Kid.

Billy the Kid, or William Henry McCarty Jr., was born on the eve of the Civil War, in an Irish neighborhood in New York City. His father remains unknown. His mother, Catherine McCarty, is thought to have emigrated from Ireland during the time of the Great Famine. In 1868 the single mother moved with her two small sons to Indianapolis. There she met and married William Antrim, 12 years her junior. It seems she fared about as well with Antrim, or perhaps worse, as she had alone. Mary McCarty washed clothes, baked pies and took in boarders to support her family. But by the time she made her way to Silver City, New Mexico in 1874, she was in the final stages of tuberculosis. In September of that year she died.

At the age of 14, the boy who would go down in history as Billy the Kid was taken in by a neighboring family that owned a hotel. There he worked for his keep, and the manager remembered him as his only employee who didn’t steal. I mention this—from the great store of legend that surrounds the outlaw—because I don’t believe young Billy was a bad sort. Although his first arrest came in 1875, for stealing a cheese, it is likely that his criminal acts stemmed more from necessity than attitude. Despite his notoriety, to me he evokes a sympathetic reading.

Nevertheless, from 1875 on Billy the Kid’s life is the stuff of the Wild West’s part myth part truth: frequent run-ins with the law, gunfights and other conflicts. Increasingly, when he was caught in the act or had some clash with authority, it was easier to shoot first and ask questions later. But this was not unique to the Kid. It was part and parcel of the outlaw culture developing—among wealthy businessmen as well as impoverished workers—in the untamed territories of the American West.

In 1877 Billy, now known as William Bonney, moved to Lincoln County, New Mexico. At first he worked in a cheese factory. Then he became friendly with a group of ranchers. Late that year, he and five others were hired as cattle guards by John Tunstall and Alexander McSween, the first a rancher, banker and merchant, the second a prominent lawyer. Tunstall in particular became a father figure to the young man, who had never known a father of his own.

Those were the days when small groups of prominent men fought one another for control of local economies. They bought up land, expanded their enterprises, opened and ran the stores that sold everything to everyone, and—when things went bad—often settled their arguments with firepower. Rather than tell the whole story of the Lincoln County war, for it is a very complicated story indeed and readers can find myriad versions in the history books, I’ll just say that, at what would be a pivotal moment for Billy, a man named William Morton shot John Tunstall dead.

Billy the Kid vowed to avenge Tunstall’s death. He joined a group of men who called themselves the Regulators. What followed were murders and counter-murders. Billy was eventually captured, promised immunity if he cooperated with a Grand Jury, and kept his side of the bargain. Following his courtroom testimony he was to have been submitted to a token arrest, briefly imprisoned, and then freed. Instead he was betrayed by the same authorities who had convinced him to testify. He was tried and sentenced to hang. Billy the Kid’s dramatic escape is legendary. He was on the run for the next few years but was finally hunted down by Sheriff Pat Garrett in 1881 and shot on July 14th of that year.

So, who was Billy the Kid? Certainly not a Robin Hood. Probably not anyone who contributed much to society. But he remains, for me, a maligned yet sympathetic character, similar to so many young men today who are pushed by injustice and lack of opportunity into lives of “kill or be killed”—whether in gangs, the wars in which they act as cannon fodder, or simply because they cannot fit in with the roles society has rigged for them.

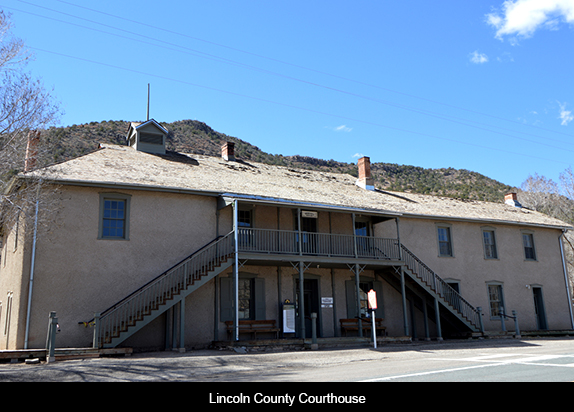

Today the village of Lincoln, New Mexico is a main street bordered by historic buildings and a few private homes. Some thirty thousand visitors each year travel to the well-kept site, now also Lincoln State Park, the apex of what is known as the Billy the Kid Loop. East as far as Capitan, west to Hondo, and also including Ruidoso, one can drive though lovely country, stopping and exploring the outlaw’s history in a series of permanent exhibits, the courthouse from which Billy escaped to operate for a couple more years, and original structures from the 1870s where he slept or took temporary refuge. The Billy the Kid story is what lures visitors, but there is much more to Lincoln County than that story alone.

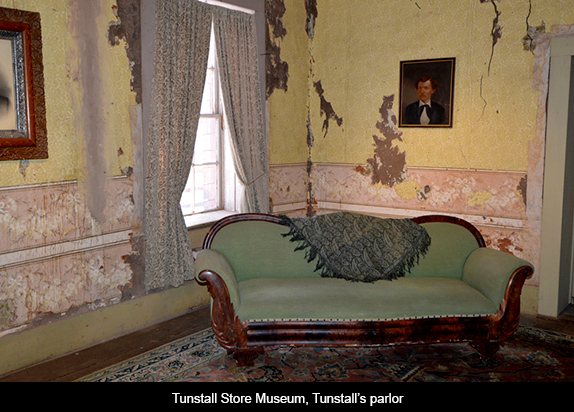

The objects preserved in several museums are fascinating and offer insight into what life on this frontier was like: an Apache cradle board and some exquisite baskets, a coffee grinder, furniture, saddles, firearms, tools, carriages, paintings, old glass, and more. A small cemetery on the eastern edge of the village is also worth a stop and a stroll among the gravesites. Tombstones from different periods in the area’s history tell stories of hard lives lived.

Driving south on I-25 from Albuquerque and turning east onto #380 just after Socorro at San Antonio, we passed through the sad little town of Carrizozo and out onto plains of ochre grasses, occasional scrubby Mesquite, and thirsty Joshua trees. A silhouette of perfect volcanic cones rises to the right. A little farther on, expansive lava fields, or Malpaís as they are called around here, extend to the horizon. Later the landscape includes hills of Juniper and Piñon, and the road begins to rise and descend, twisting and turning past the entrances to prosperous looking ranches. Smoky Bear is from these parts, and we saw many signs of his staunch presence.

As we drove past the road that leads to the Trinity Site, two opposing words lodged in my mind: pride and shame. The spot where the United States tested the first atomic bomb is an emblem of pride to many. To me it is one of shame. Los Alamos, where the bomb was developed, and Trinity where it was tested, are testaments to US scientific ingenuity but also to the horrors of conquest. Along with reducing Indian tribes to corralled peoples, bringing slaves over from Africa, and sending loyal Japanese Americans to detention camps during World War II, unleashing the murderous fury of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki are deeply shameful chapters in our history.

Although much of the suffering and death in those two Japanese cities was long-term and statistics are therefore inexact, it is estimated that 80,000 people perished at Hiroshima and roughly half that number at Nagasaki. Disease, suffering and premature death went on for years; it still does. The official US narrative is that those bombings ended World War II, thus saving thousands of US lives. But it has now been well documented that the Japanese were ready to surrender, making such a criminal show of brutality unnecessary. The bombings were clearly meant to send a message of unrivaled power.

One of Hiroshima’s survivors was Shigeko Sasamori, 13 when “Little Boy” (the bomb’s code name) devastated her city of Hiroshima and killed most of its citizens. Shigeko has dedicated her life to speaking out against war. She has been in Albuquerque on several occasions. In July 2005 she was invited to "Blast From the Past," a celebration of the 60th Anniversary of the Trinity Test put on by the National Atomic Museum. Two anti-nuclear groups paid her way to it so they would have to look in the face of what they had done. It was very hard for her, even though she was flanked by two men, one from each of the groups. She and the other delegates were given pink backpacks embossed with an image of the mushroom cloud, and a pair of little pink goggles as souvenirs. Albuquerque poet Mary Oishi, who accompanied Shigeko to the commemoration, says she left both at her house before flying back to Japan. They weren’t items she wanted to keep.

As we drove through the changing countryside, dotted with occasional grand ranch houses and reaching out to a skyline of distant mountains, Shigeko came to mind. I thought about her serene demeanor and twisted hands. Pride for her. Shame for us.

Entering Lincoln, the dual emotions continued to provide a silent but potent backdrop to the history that put this place on the map. The pride of the town is evident in its beautifully restored buildings, and the few private homes built in similar styles and showing the same delight in historic authenticity (sixty percent of the village is museum). The architecture and period pieces contained within are well worth a visit. The events upon which the town focuses, however, evoke something less deserving of pride.

I was most struck by the similarity between the bands of nineteenth century outlaws with their routine killings and those who hold power in today’s world, when wars—declared and undeclared—kill lawlessly and, as was true 150 years ago, the instigators so often go unpunished. Rather than accountability there is often applause, as if history melts into some amorphous sea of sordid justification.

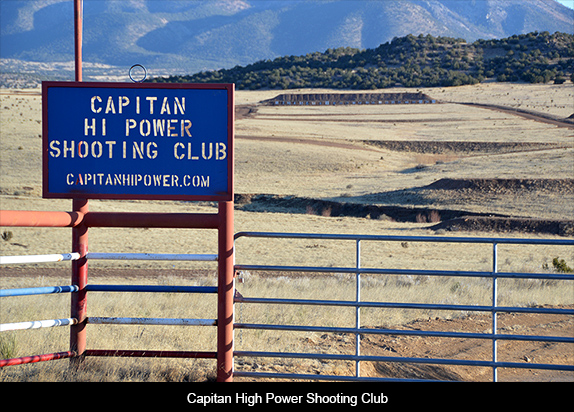

Just outside Capitan, we passed a large target range with a sign reading: “high powered shooting club.” In the Lincoln County War the gunslingers were mostly hapless men in the rude employ of gentleman outlaws hoping to make great fortunes. Billy the Kid himself was but a pawn in the game. Pride and shame: the former overblown, raucous, and leading to senseless death, the latter the hook upon which the fortunes of a lovely village depend. One hundred fifty years later we have those intent upon keeping high-powered weaponry in the hands of ordinary citizens and those struggling toward more rational solutions to human conflict: co-existence, debate, mediation. Once again, or still, shame and pride.

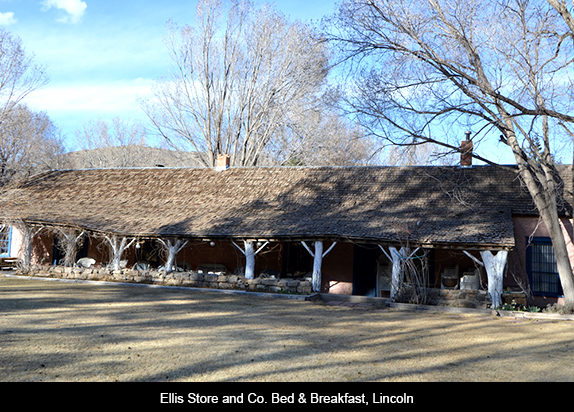

But there is much more to historic Lincoln than Billy the Kid or the Lincoln County War. Architecturally, walking along Main Street is like being transported back to the last two decades of the 19th century. We spent the night at the Ellis Store and Company, a delightful bed & breakfast at the far edge of the village. The main house was built around the two oldest rooms in the area, dating to 1850. Billy the Kid is said to have slept in one of them, and we chose it for our overnight.

The room’s guest book contained entries from travelers who’d come from as far away as St. Petersburg, Russia. One visitor from Texas wrote about what a thrill it was to stay in a place owned by her ancestors; she traced her roots to the old Ellis family. A large gristmill, now part of the B & B, once sat on the meandering river to the rear of the property. It was later moved to its present location.

Other not to be missed buildings and houses are the Lincoln County Courthouse (1873-74), now a museum, where one of Billy’s famous shootouts took place; the old Tunstall Store (1877) with its fascinating array of period merchandise; and the Wortley Hotel, whose first rooms were standing in 1874. During the Five Day battle, the Wortley served as Dolan’s command post. Among the hotel’s many owners was Sherriff Pat Garrett, who lived there for two and a half months in the summer of 1881.

The Torreon (date unknown), a circular stone fortress, is also an interesting structure, very different in style from most of the other houses and buildings which are Territorial. The Community Church (1887) was previously a school. A new and very informative visitors center and museum is a good point of departure for seeing all of these (there is a $5 admission and your ticket includes several other state-owned sites).

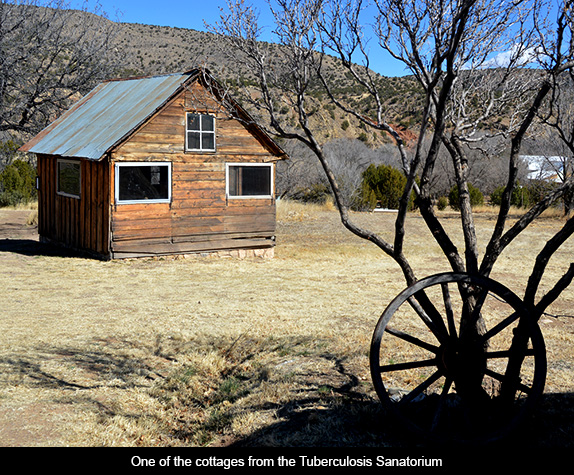

The Ellis House, where we stayed, is one of the village’s earliest structures. It was purchased by Isaac Ellis in 1877 and was used as a ranch headquarters, store and boarding house. It also did a stint as a tuberculosis sanatorium in 1903, when Dr. James W. Laws bought the property and expanded it to include an annex and individual cottages for his patients. During this time the mill housed nurses. Dr. Laws suffered from tuberculosis himself, so was both doctor and patient.

Several galleries along the main street sell art and antiques. My favorite among them was Dickinson’s Store, run by Seal, a gracious and knowledgeable woman who recently moved to Lincoln from Roswell.

We were told the season for visiting Lincoln ideally begins in April, after the March winds and when those establishments that have closed for the winter have reopened. We were there in late February, the winds were already gusting dramatically, and only about half the attractions were viewable. We were able to see the major sites, such as the courthouse, and a kind park ranger unlocked the Tunstall store for us, which was a treat. But no food was available, so we drove back to Capitan for a tasty lunch at Renee’s (delicious home cooked breakfasts and lunches from Thursday through Saturday, closed for baking on Mondays), and then past Hondo to Tinnie, for dinner at the elegant Silver Dollar, an experience not to be missed.

A short distance from Hondo, just off State Highway 70, is San Patricio where the Hurd Gallery is also worth a stop. The beautifully appointed building is on the ranch where Peter lived and worked, and exhibits paintings by the whole talented family: Peter, Henriette Wyeth, and their son Michael. Works by N. C. and Andrew Wyeth are also on display. A nearby iris farm and gallery are also inviting. This whole area is chile-growing country; in two days we ate green chile in several dishes, and the native pepper is surely one of the crops of which New Mexico can be justly proud.

On state road #380, just before entering the tiny community of Tinnie, an immense billboard assaults the eye. On a plain white background in black block letters is a single word: FORGIVE. The word stands alone like some strange message from the beyond, undoubtedly placed by one of those religious sects eager to promote its “end times” message. I was mystified. Such messages are more likely to feature words such as REPENT or OBEY.

We pulled over and I took a picture of the sign. I knew it had nothing to do with my deep shame for what has been perpetrated in all our names, but its presences nonetheless made me shudder. From whom do we ask forgiveness, and whom do we forgive? The criminal madmen who, overcome by greed and wallowing in their lust for power, vie for control in every century?

Ourselves?

March 14, 2014