It would be hard to find two countries whose concepts of the state/citizen relationship are more dissimilar than Cuba and the United States. Since its 1959 victory, the Cuban revolution has prioritized free and accessible healthcare as a basic right for all. It is right up there with education, work, and other human rights. The country experimented with how best to deliver healthcare, and thirty years ago came up with a program it has been tweaking and improving ever since.

Basically, the National Family Doctor and Nurse Program is a network of core groups made up of a family practice doctor, nurse practitioner, pediatrician and in some cases someone of another specialty. These professionals live and work in every city neighborhood and rural community. The idea is for them to become acquainted with individuals and families (the average number of people per team is now around 1,500), learn their life habits (do they suffer from diabetes, alcoholism, is there domestic abuse?), and be able to identify risk factors and treat their constituents in wellness as well as in whatever crises they may face.

Over the years, I’ve visited the neighborhood doctor’s home in several areas, and been treated to karate exhibitions put on by local kids as well as to explanations of the health work and results obtained. When a person requires more specialized treatment, he or she is referred to a polyclinic—the next step up the pyramid—or, if needed, to a specialty hospital or treatment center.

Cuba is still a poor country. And it suffers from a number of problems aside from the blockade launched against it by the United States for more than half a century. With its island climate, it has been prone to epidemics of tropical disease. It has one of the highest numbers of cigarette smokers of any country in the world. Alcoholism is a problem. And its population is aging fast: it suffers from a very low fecundity rate, and 18.3% of its 11.2 million people are 60 years or older. This number represents a 30% increase over the year 2000.

Despite these challenges, and others, the fact that Cuba prioritizes quality healthcare allows it to make notable progress. A recent article by the American Board of Family Medicine noted, “In 2013 the country recorded its lowest infant mortality rate ever: 4.2 deaths per thousand live births. This is lower than anywhere else in the Americas, even the developed North. US health researchers have visited Cuba to try to understand how such an impressive outcome is possible in a grievously resource-limited setting.”[1]

It would take an article way beyond the scope of this one to look at all health-related situations, mental as well as physical, and give a sense of what Cuba is doing in each area. When an important crisis is identified—HIV/AIDS, periodic bouts of dengue fever, or the 1994 epidemic of optic neuropathy, to name only three—the social sciences and other areas of expertise as well as a broad spectrum of medical specialties come together to analyze and attack the problem. Resources are enlisted to keep Cubans healthy the way they are rallied to go to war here, in line with our very different set of priorities.

HIV/AIDS is a case in point. When the pandemic first hit the island, Cuba’s healthcare ministry established a center where people diagnosed with the disease were brought to live. This protocol at first drew bafflement from Cubans themselves and angry criticism from abroad. But LGBQ visitors soon took a harder look at the protocol and began issuing cautiously supportive statements. A general education and outreach program was launched nationwide. Residents of the center were educated about their condition as well as given the most advanced treatment and medication free of charge. The place was beautiful and peaceful, made up of small houses with all the amenities. People got jobs, and were given the option of returning to their communities. Some did, while others chose to stay. In a relatively short time, Cuba became one of the only countries in the world in which HIV/AIDS was fully controlled; the number of cases remained steady and then began to decline.

Cuba not only considers the health of its own citizens a basic human right. The country attends to the health of hundreds of thousands beyond its borders. Back when I lived there (1969-80), great numbers of visitors traveled to the island to undergo operations or receive other sorts of medical attention. All these services were free. Today the country is forced to charge for them, although their cost is far below what a person would have to pay for similar attention in the United States. Similarly, the vast number of doctors and other medical personnel Cuba once volunteered to work in poorer less developed countries around the world now charge for their services in those countries that can afford to pay. In others they remain free.

I want to talk a bit more about this Cuban medical personnel that serves overseas, because it constitutes a shining example of the way in which the revolution offers its internationalism to people in need. During the 1980s, I experienced first-hand the work of Cuban doctors in Nicaragua. Every country with medical needs is invited to call on Cuba for help. To date Cuban medical personnel serve in 69 countries. Following great natural disasters (earthquakes, floods, fires), many nations have requested Cuban aid. Doctors and other health personnel arrive ready to go to work, with campaign hospitals that can be set up in days. After Katrina, Cuba offered its aid to the city of New Orleans, but was refused.

In Latin America and the Caribbean alone, an estimated 2.8 million people are blind and 11.2 million visually impaired. Two-thirds of these conditions are reversible, with procedures such as cataract surgery. These figures prompted Cuba, in 2004, to develop a regional partnership for vision restoration known as Operation Miracle. It began as a bilateral program between Cuba and Venezuela; Cuban teachers working in Venezuela’s literacy campaign noticed the extent of blindness in the population. By 2008, the program in that country alone was averaging 5,000 free surgeries a month. As of March of that year, 1,035,566 people from 32 countries had their vision improved or fully restored. And the program has now been extended to Africa and China.

Cuba has traditionally had excellent doctors, but many of them—lured by seductive offers from US hospitals—left after Fidel Castro and his movement came to power in 1959. They were part of a massive brain drain aimed at destabilizing the revolution. For a while there was a crisis of medical personnel on the island. But the revolution quickly set about to train more doctors and other healthcare workers. Following a completely free education, they were required to provide two years’ of social service in underserved parts of the country. Today one of the tragedies of Cuba’s difficult effort to preserve its brand of socialism in the face of a globalized economy is the fact that a number of excellent medical providers have left their professions and are working in tourism, where their earning capacity is greater. Cuba recently raised the salaries of medical personnel across the board, but must find additional ways to keep these specialists working in the areas for which they have been so well trained.

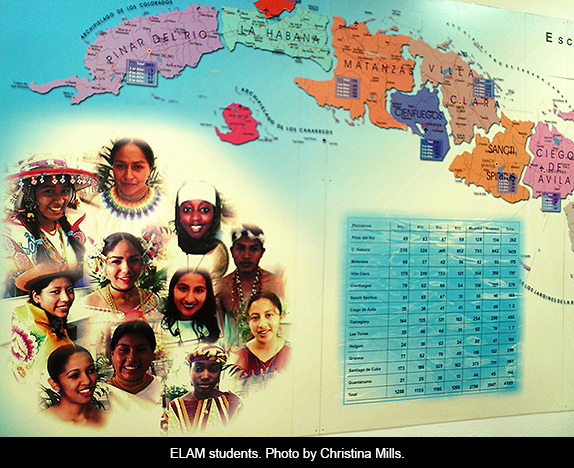

The ELAM (Latin American Medical School) has its beautiful main campus in Havana. But the country has 14 medical schools and three independent study centers, where 13,282 students from 124 countries currently earn high quality degrees. The ELAM’s first graduating class was in 2005. More than 10,000 low-income students from Africa, Asia and the Americas (including the United States) receive scholarships. They represent 101 ethnic groups. These students make a commitment, once they finish their studies, to work in underserved communities at home.

World Health Organization Director General, Dr. Margaret Chan, when she visited ELAM in October 2009, said: “I know of no other medical school with an admissions policy that gives first priority to candidates who come from poor communities and know, first-hand, what it means to live without access to essential medical care. For once, if you are poor, female, or from and indigenous population, you have a distinct advantage.”

Cuba has also developed an astonishing biotech industry. According to a 2004 WIRED article, “The Cuban Biotech Revolution”:

In 1981, half a dozen Cuban scientists went to Finland to learn to synthesize the virus-fighting protein interferon. Castro sent them with money for a shopping spree. They brought back a lab's worth of equipment and took over a white stucco guesthouse in the Havana suburbs; a decade later, Cuba was the pharmacy of the Soviet bloc and [so called] third world. Most trade took the form of barter, and development experts estimate that by the early '90s the business was worth more than $700 million a year.

"And then, almost from a Monday to a Tuesday," says Carlos Borroto, vice director of the Cuban Center for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology (known as CIGB in Spanish), "the Soviet Union collapsed." Cuba lost all its credit, 80 percent of its foreign trade, and a third of its food imports.

The Cuban revolution had to invent to survive. What Cubans call The Special Period (a time in the early 1990s, when everything was scarce and people had to tighten their belts even more than had been previously necessary) produced one notable success. Faced with economic calamity, the revolution did something remarkable: It poured hundreds of millions of dollars into pharmaceuticals.

One beneficiary was Concepción Campa Huergo, president and director general of the Finlay Institute, a vaccine lab in Havana. She developed the world's first meningitis B vaccine, testing it by injecting herself and her children before giving it to volunteers. "I remember one day telling Fidel that we needed a new ultracentrifuge, which costs about $70,000," Campa says. "After five minutes of listening he said, 'No. You'll need 10.'"

Cuba got so good at making knockoff drugs that a thriving industry took hold. Today the country is the largest medicine exporter in Latin America and has more than 50 nations on its client list. And at the same time as they were selling generics, the science-heroes were inventing. The revolution made biotechnology one of the building blocks of the economy. As of 2004, researchers had been granted more than 100 patents, 26 of them in the US. They’ve since set their sights on Western markets.

Albuquerque has important links to Cuba’s health system. Two graduates of ELAM have recently completed residencies at the University of New Mexico medical school’s Department of Family Medicine. MEDICC (Medical Education Cooperation with Cuba) has one of its most successful programs in our city’s South Valley; some 35 health leaders and community residents have gone to Cuba from 2008 to 2010. We have many Albuquerque healthcare initiatives informed and inspired by Cuba’s system.

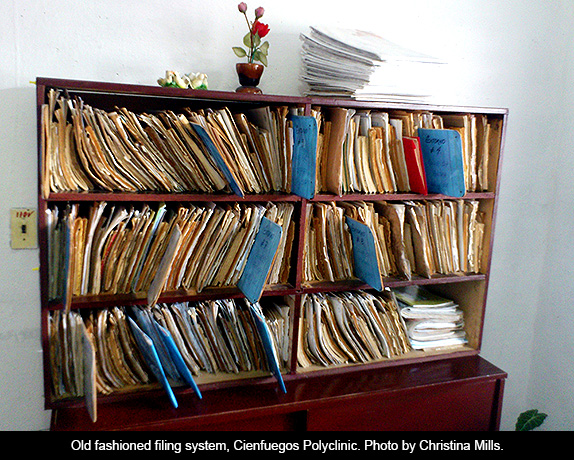

This is all about priorities. Cuba, as I say, is still a poor and in many ways underdeveloped country. US Americans who have seen the Michael Moore film Sicko, have a sense of the kind of healthcare available in the country. That film did a good job of comparing the differences in ideology between Cuban and US medicine. It was less accurate when portraying Cuban medical facilities. The hospitals shown were new and well equipped. It’s not that this sort of hospital doesn’t exist there; it does. But many more Cuban hospitals and clinics are in old buildings with out of date equipment. An effort has been made to create outside the box; one example is the plethora of milk banks where mother’s milk is stored and given babies whose mothers cannot nurse.

Because of the blockade, Cuba still has trouble obtaining the latest in medical journals, instruments and sometimes even needed medication. Many visitors come bringing medications, sterile gloves, and other supplies. I know of instances in which Cubans have had to bring their own sheets or light bulbs for a hospital stay, or in which family members have had to aid nurses in less serious situations. As the country is able to get back on its feet economically, more funding is made available for healthcare.

Despite these lacks, in today’s Cuba you can be sure of a well-trained doctor, the highest quality diagnostic aids, and—above all—a different mentality when it comes to disease prevention and access to care. Cuban medical personnel are not beholden to the mega insurance or pharmaceutical companies. Patient consultations are not limited to ten minutes. Diagnosis and treatment takes place within a holistic paradigm. Healthcare is not a privilege. It is a right.

[1] Neggers Y, Crowe K. Low Birth Weight Outcomes: Why Better in Cuba Than Alabama? J Am Board Fam Med. 2013 March-April;26(2):187-95. Quoted in MEDICC Review editorial, January 2014, Vol 16, No 3.

May 23, 2014