Here in the US American Southwest, when we speak of the Canyon we usually mean Grand Canyon. But there are many other canyons, one system of six not that far south of us in Mexico’s large border state of Chihuahua.

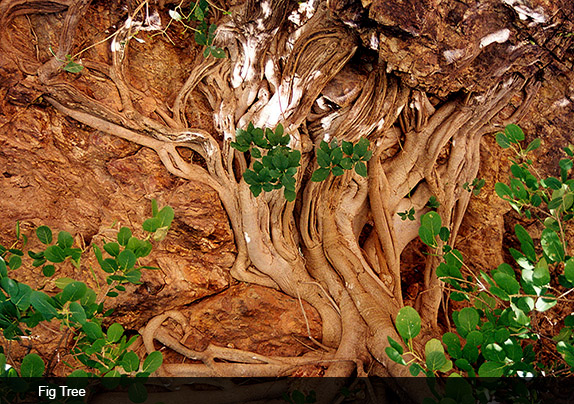

Barranca del Cobre, or Copper Canyon, is actually a system of linked canyons four times larger than the one in northern Arizona. They couldn’t be more different from the latter. While ours reveals a dramatic landscape of millions of years of multicolored rock, Copper Canyon is vast undulating green studded by giant cacti and twisted roots of fig trees. While our Canyon accommodates tourism in a sophisticated array of attractions, Mexico’s struggles to contend with it. While the Havasupai and Hualapai Indians who live in hidden corners of Grand Canyon have adjusted to modern life and even manage to draw some income from their locations, the Tarahumara or Rarámuri who inhabit Copper Canyon are stressed by extreme poverty, outside drug interests, and violence.

The Tarahumara are runners. Although they are exceptionally good at it—men often run more than 100 miles in a day—running is not simply a sport to them. It forms part of their complex cosmology. As they run, men often kick small hard rubber balls; women use sticks to tap large hoops, sending them spinning before them.

In 1993 and ’94, several Tarahumara runners entered the famous 100-mile Leadville foot race in Colorado. Although the race organizers tried to make them wear running shoes and confused them with signage they could not read, they won both years. In 1993, 53-year-old Victoriano Churro came in first, followed by a 41-year-old friend and teammate who came in second. The following year a five-man Tarahumara team again entered the ultra marathon; 25-year-old Juan Herrera won with a record time of 17 hours and 40 minutes.

Non-Indian competitors at Leadville run, as most marathoners do, for the prestige and prize money. The Tarahumara ran for their community. Although they are a somewhat nomadic people, living in caves and small wooden huts throughout their vast homeland and moving often, community is central to their sense of place. The money they brought back from Leadville bought a year’s worth of rice and beans for dozens of families.

My first contact with a Tarahumara runner took place almost half a century ago, but it is as vivid to me now as when it happened. It was 1968. Mexican students, like other young people in places such as New York and Paris, were embroiled in a movement for university autonomy and other demands. In Mexico City the movement had exploded across the vast metropolis. I lived there at the time, and was involved. Our marches and rallies became more and more massive.

At one of those rallies two Tarahumara men approached the microphone. They had run from the northern part of the country, just to offer us their support. The older man spoke in his Uto-Aztecan language; the younger translated his words into Spanish. Their message was brief and to the point: “We have always mistrusted the government, but now we know it is truly evil because it is killing its own sons and daughters.” Then the two men turned around then, and ran more than a thousand kilometers back home. The Mexican Student Movement was eventually defeated at the terrible massacre of Tlatelolco. Mexico was about to host the 1968 Olympic games, and couldn’t risk losing its investment.

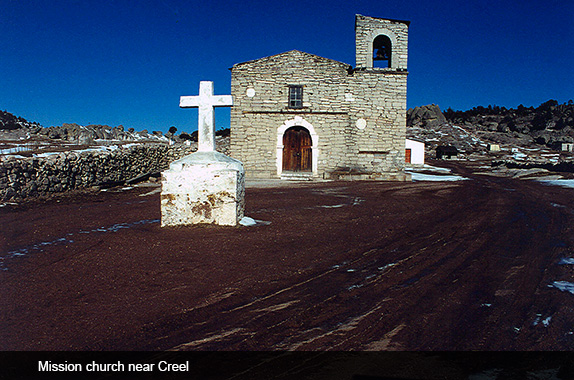

As that experience demonstrated, the Tarahumara people speak little but have a lot to say. They call us “barking dogs” because in their sense of things we talk a great deal but say little. Tarahumara religion or worldview is a syncretic mix of indigenous belief and Roman Catholicism. God the Father is symbolized by the sun. The Virgin Mary is a modern incarnation of a primeval female deity called Eyerúame. The Tarahuamara believe that the afterlife is a mirror image of our world and that good deeds should be performed not for spiritual reward but for improving life here on earth. The Tarahumara share with other Uto-Aztecan tribes a veneration for peyote.

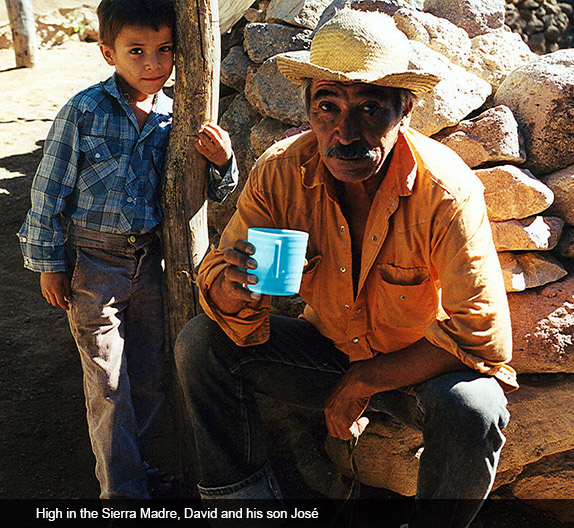

The Tarahumara are an extremely poor people. And their lives are being profoundly jeopardized by climate change. Severe drought has affected their homeland for more than a decade now. Agricultural losses in the state of Chihuahua are estimated to be around $250 million in US dollars, and 180,000 head of cattle have already succumbed. All this touches the Tarahuamara is a variety of ways. First, unequal contact with the outside world produced a dependency they had not previously known. Then the closing of big cattle operations reduced their employment opportunities, and their own farming plots and grazing opportunities also suffer from a lack of rain. Although the Mexican government sends relief, it is never enough. Mexico’s Human Development Index (HDI) lists life in the Sierra Madre as the poorest in the country, almost 50% below the national average.

The Copper Canyons are located in Mexico’s Sierra Madre Occidental, the mountain range in southwestern Chihuahua of Treasure of the Sierra Madre fame. These canyons were carved by six rivers, which eventually merge into the Río Fuerte and empty into the Sea of Cortéz.

We know the area as a tourist destination: Arizona “snowbirds” load their motor homes on flatcars that take them via the Chihuahua al Pacífico Railroad along the rim of Urique Canyon from Chihuahua City to Los Mochis. Some visitors brave the dangerous mountain roads, often clogged with logging trucks, and drive their own cars to destinations such as the lookout point at Divisadero, the small town of Creel or the mist-filled Valley of the Monks, an area where stone monoliths play hide and seek with clouds. The most adventurous may embark on multiday hiking expeditions into the canyons themselves. Except for the train travelers, Copper Canyon is still a wilderness that has been little explored.

It wasn’t always like that. Batopilas, today a sleepy little village at the bottom of the canyon of the same name, was once one of Mexico’s largest modern day urban centers and the second to enjoy electricity.

Batopilas and the US share a dramatic history. The Spanish first mined silver ore in the area in 1632. Two hundred fifty years later, Alexander Robey “Boss” Shepherd was territorial governor of the District of Columbia. Washington itself was a city of muddy streets and unpaved sidewalks back then. During his three years in office, Shepherd built roads, sewers, gas and water mains. He was called Father of Modern Washington. But, like so many civic leaders, he was also a crook. When his malfeasance was discovered, he was chased out of office.

Shepherd never served time. Instead, he moved his family to Batopilas in 1880. He purchased a silver mine and then laid claim to 300 others, quickly consolidating his Batopilas Mining Company. Then, instead of shipping out raw ore, he constructed a complete processing plant. The processed silver was cast into bars, loaded two bars per mule, and carried by monthly trains of 100 mules each all the way across the mountains to Chihuahua City. The same mules that carried the ore out brought objects of refinement in: grand pianos, fancy furniture, elegant china and tea services. Between 1880 and 1906, 20 million ounces of silver were extracted, making the Batopilas mines among the richest in the world. At the operation’s peak, it employed 1,500 workers, most of them Tarahumara Indians.

The crook turned magnate built bridges, aqueducts and a hydroelectric plant, turning the poor village—at least for its owner class—into a thriving community. Many of the old colonial houses still stand. Some have been renovated with great attention to history, beautiful interior patios, and with local cabinetmakers fashioning period furniture and artists contributing murals and other details. But the town that once supported 5,000 inhabitants now has only around 1,000. Although Batopilas itself has a school and a clinic, the Tarahumara people who mostly live scattered in the rugged canyons have little or no access.

Shepard’s once luxurious hacienda now lies in ruin. Exploring it is fascinating. You can wander through the main house, stables, servant quarters, and gardens. In the late afternoon, rays of copper light glow on the old brick and through broken windows and doors. A great fuchsia bougainvillea drapes itself over one wall.

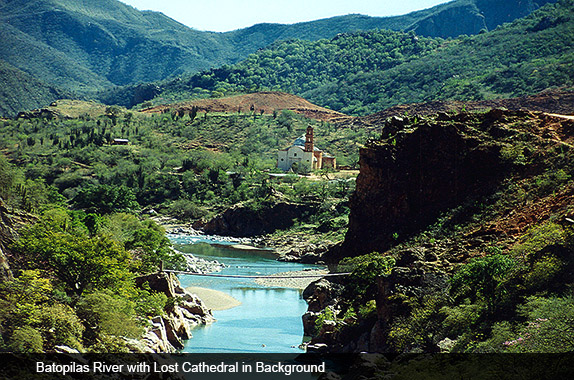

Another ruin not to be missed if you visit Batopilas is the Lost Cathedral at Satevó. Satevó is a tiny community about 4 miles along the river from Batopilas. Given the number of houses—and no one I spoke with seemed to think there had ever been more—it seemed strange to see such a large church. Stories regarding its history abound, and most of them are contradictory. I’ve read that the Lost Cathedral was built in the early 1600s, and also in 1760. Perhaps these dates bracket the building project. It is agreed that Jesuits, who tried to Christianize the area, constructed the cathedral; and that it was one of five built by them. To my knowledge the other four have not been found.

The first time I saw the Lost Cathedral it looked abandoned. Only its beautiful architectural lines spoke of a once-imposing edifice. Bullet holes—perhaps from the Mexican Revolution, perhaps from some local skirmish—pierced the façade. Where an immense and many-armed cactus rose beyond the tall roofline in back, crude cement patches had not yet been coated with stucco or painted. When I returned a few years later, a great deal of restoration had taken place, both inside and out. It still looks as if funding for repair work has been spotty, but the location alone of this graceful building nestled just beyond a tiny footbridge that spans the Batopilas River makes a visit worthwhile.

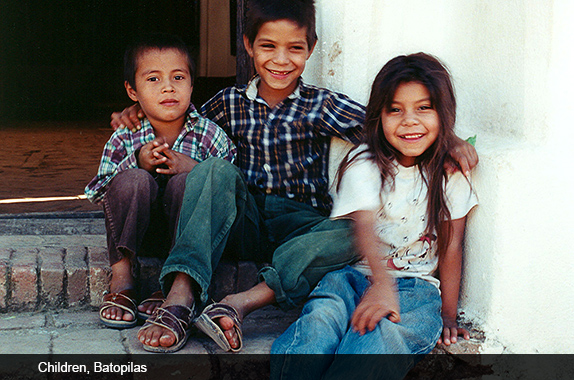

Walking back from Satevó, I lingered to talk with kids I met along the way. I passed a graveyard, and took time to explore the headstones, many with interesting symbols. I spent time with a coffin maker who was working outside in front of his shop. And with a silversmith, and a man who made leather-soled sandals with long leather strips to tie above your ankles. Most of the Tarahumara people I saw were barefoot and most of the townspeople wore ordinary shoes, so I imagined the sandal-maker was hoping for an increase in tourist trade.

The issue of tourism in the Copper Canyons has been complicated. The train trips are clearly well integrated into the national tourist industry. Creel, which I remember from the 1960s when I lived in Mexico as a ghostly little mountain community, has grown to embrace a thriving population of 6,000. It offers important social services beyond its urban limits, promotes the Tarahumara’s rather simple crafts, and has also not been immune to the country’s growing problem with drug violence. In 2008 the place was blown apart when a heavily armed gang attacked 14 locals as they chatted on a street. All but one died.

Visitors continue to travel to Divisidero and other destinations along the canyons’ rim. In the depths of the canyons, though, several entrepreneurs who once owned hotels have sold them because they feel the influx of outsiders hasn’t brought anything positive to the Tarahumara people.

Advertising that misrepresents the Tarahumara lifestyle lures visitors expecting to see “nobel savages” living in a primitive but “pure” way. The more observant among the outsiders soon realize that it is modernity itself that is destroying the Tarahumara habitat and way of life. Noodles that come in plastic-foam tubs, foil-wrapped potato chips, and plastic bottles of Coca-Cola are all available in the mountains. Many Tarahumara seek to gain from tourism by attempting to meet the outsiders’ romantic expectations. The Tarahumara way of life has changed more in the past several decades than in the preceding 300 years, but little of that change has meant an improvement in their lives.

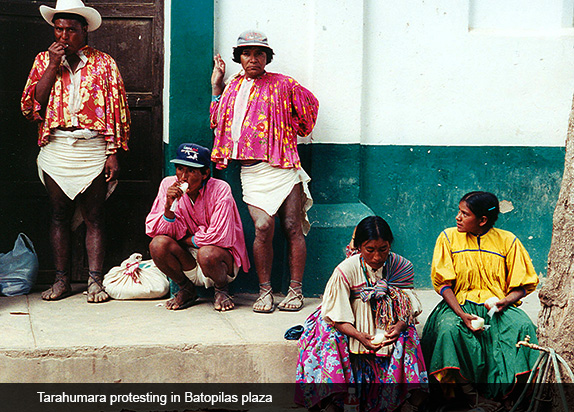

I once witnessed a gathering of Tarahumara in Batopilas’ small central plaza. They had come together demanding a road on which they could take their sick to obtain medical help, and they were angry because the federales were going after family marijuana plots rather than the large-scale drug operations run by the narco- traffickers. As far as I know, they never got a resolution to their problems.

Still popular are a number of hiking trips into the more isolated parts of the canyons. These are rugged, for people who are extremely fit and not interested in hot showers or flush toilets. Those able to make such journeys are privileged to be able to experience a countryside untouched by civilization. I suspect they may still be able to make authentic contact with the inhabitants of the canyons.

The people indigenous to Copper Canyon have not only been touched by the Spanish conquest of Mexico. They have also been influenced by the presence of Irish travelers, probably in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. One can hear the Irish lilt in some of their music, performed on small rather crude handmade violins and large but shallow handheld drums. They also play three-holed flutes made of river cane. Making your way from the rim to canyon bottom, whether aboard a decrepit bus or in a four-wheel drive touring vehicle, you can often hear one of those flutes being played by a lone shepherd. Its sound echoes across the rough terrain. Sometimes another flute answers from miles away.

Like so many other parts of Mexico, in the Barranca del Cobre a beautiful culture is being lost, people are struggling to survive, and the threat of wholesale violence is ever present. It is a place that deserves a visit from anyone interested in experiencing values fast disappearing from the world we are trying to preserve.

November 08, 2013