Frida Kahlo (1907-1954) was one of Mexico’s most innovative and brilliant artists. She not only painted, sketched, wrote searing journals, and entertained at exquisite meals. She made of her home and person a public statement of indigenous tradition, female identity, surrealist vision, and unwavering leftist politics. Her presence was like no other, and in 1938 André Breton described her art as “a ribbon wrapped around a bomb.”

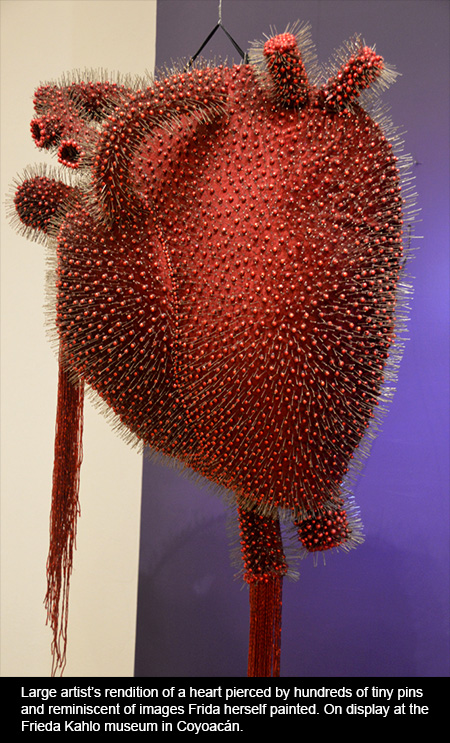

All this was part of a lifelong effort against the confines of women’s social place, and her painful misfortune. The Mexican revolution exploded when she was three, and she often gave her birth year as 1910—perhaps to seem younger than she was, perhaps, as she sometimes said, because she wanted her birth to be seen as coinciding with that of modern Mexico. Gunfire in the streets accompanied her child’s play. At six she was stricken with polio. It is also thought that she may have been born with spina bifida. Neither condition was understood as well as it is today, and a withered leg and twisted spine plagued her for as long as she lived. All this was further complicated by an accident she suffered as a teenager, when a bus on which she was riding collided with a trolley. An iron handrail pierced her abdomen and uterus, and she endured a broken spinal column, shattered collarbone, cracked ribs, broken pelvis, dislocated right foot and shoulder, and eleven fractures of her right leg. She would never completely recover from the problems these injuries caused. She could not bear children, and her lifelong custom of wearing the long indigenous skirts that became her hallmark was undoubtedly an effort to cover the deformities.

Despite all this, Frida knew who she wanted to be and what she wanted to do. Early on, she intended to study medicine but soon turned to painting. The first time she saw the great Mexican artist Diego Rivera (21 years older than she was, and already a painter of note) up on a scaffold working on one of his murals, she knew she wanted to show him her own incipient work—and also marry him. He encouraged the former, and they did marry, sustaining a volatile off again on again relationship until her death. He said the day she died was the most tragic of his life, and added that he realized too late that the most wonderful part of his life was his love for her.

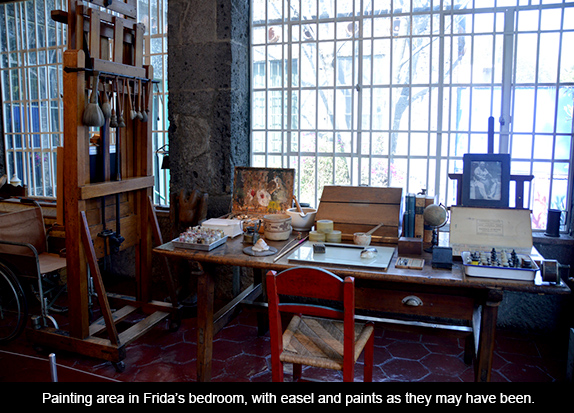

Although Frida traveled widely throughout her life—showing her work and gaining admiring attention in Europe and the US—Frida was born, lived, and died in “the blue house” in Coyoacán, a beautiful suburb now incorporated into the vastness that is Mexico City. The house would become a shrine, the museum where one can go to view many of her paintings and have a glimpse of the extraordinary creativity she wove into every facet of her life. The furnishings she chose to keep or acquired, her great collection of retables (small paintings on tin depicting miracles asked for or received), the Judases (giant papier-mâché figures meant to be laced with fireworks and set on fire just before Easter), the very Mexican style of her kitchen, her four-poster bed with its butterfly collection on the underside of the canopy, her painting easel and paints, as well as many of her paintings, drawings, and ephemera of her times, all give the visitor a sense of who this remarkable woman was. Her ashes are in a pre-Hispanic urn shrouded in a richly embroidered Mexican rebozo atop her bed.

Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera were members of the Mexican Communist Party and remained true to their ideals, supporting Leon Trotsky when he was being persecuted by Josef Stalin and forced to flee the Soviet Union. They took him in for a while upon his arrival in Mexico. They eventually broke with Trotskyism and became supporters of Stalin in 1939. While Rivera expressed his political ideas in his work, Frida’s was more personal, intimate, even mystical.

During their marriage Frida and Diego both had affairs with others. She was bisexual, and we know of important relationships with such as Isamu Noguchi, Josephine Baker, Tina Modotti, and Leon Trotsky. His affair with her sister Christina was a blow from which Frida may never have recovered. The couple sometimes lived apart or in adjoining spaces, divorced in 1939, remarried in 1940, and were together again at the time of her death.

Toward the end of her life, Frida’s physical ills became more severe and she was often immobilized and in great pain. Her right leg had to be amputated at the knee. Her last public acts were attending a large exhibition of her work at a Mexico City gallery (she had to be brought there in her bed), and, in her wheelchair leading a demonstration in support of Guatemala, just invaded by US troops intent upon overthrowing the democratically elected government of Jacobo Arbenz.

A few days before her death at the age of 47, she wrote in her diary: “I hope the exit is joyful – and I hope never to return.” Her death certificate claimed she died of a pulmonary embolism, but no autopsy was performed. She may have taken an overdose, which may or may not have been intentional. She was cremated as she wished, and as her body moved toward the crematorium’s flames it is said that the heat caused it to jackknife and sit, her unbraided hair swirling out from her face. Frida’s life had ended. Her enduring legend was born.

Much as in the case of Che Guevara, this legend is stoked in items of popular culture—T-shirt images, cheap jewelry, and reproductions of her work—as well as in serious scholarship and attention to historic evocation Mexico does so well. The blue house in Coyacán is a magical space. It has been depicted in many films, the best known of them Frida starring Selma Hayak (interestingly, the filmmakers never received permission to shoot on site, and the entire environment of that film is the brilliant creation of Julie Taymor).

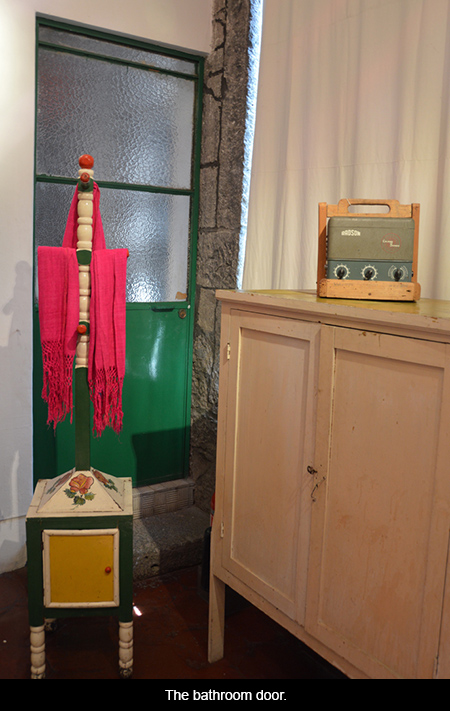

I’ve been to Frida’s house at least a dozen times over the years. Often with my daughter Ximena, for whom Frida is especially important. On a recent visit, though, I had a particular desire. I wanted to enter the contested space of Frida’s bathroom, the bathroom off her bedroom, the door of which had long been locked.

The story is as follows. When Frida died, Diego ordered Dolores Olmedo (a family friend who would assume directorship of the museum) to keep this bathroom closed for ten years. Olmedo took the directive so to heart that she followed it until her death—fifty years after it was locked. When the new museum director took over, one of the first things she did was open the bathroom.

What was inside? Mexican novelist, essayist and political activist Elena Poniatowska was present at the opening, and wrote an important article for La Jornada de Mexico describing the event. In 2008 two galleries joined two publishing houses to bring out the intensely interesting book called Frida’s Bathroom, if you open it in one direction, and Demerol With Expiration Date if you open it in the other. The first title applies to a series of photographs by Graciela Iturbide, the second to an essay by Mario Bellatín. In combination, these expressions in different genres give one the feeling of having explored that contested space at the time of its revelation to the wider world.

Which is a good thing. Because as it turned out, and although on my recent visit to the blue house I was accorded every courtesy, I was not in fact able to enter that space myself. It was a Thursday, and the museum was crowded with visitors. Had it been a Monday when the house was closed to the public, my hosts assured me, they would have opened the clouded glass door and allowed me a glimpse inside. As it was, that was impossible. In any case, they said, I would not have been able to enter because the bathroom is now being used as a storage room and is full of boxes.

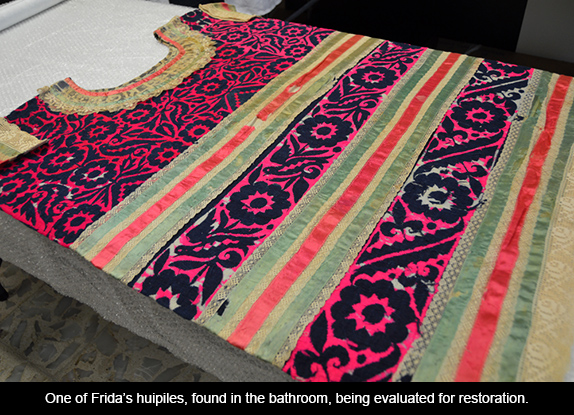

To make up for the impossibility of entering that space, the keepers of Frida’s legacy were kind enough to allow me access to what had been taken from it. In a room off limits to the public, more than 100 acid-free boxes contain many of the elaborate huipiles and other outfits, even Frida’s cotton stockings and a tattered blue-green bathing suit that looked as if it would fit a ten-year-old. These relics are currently being evaluated to determine which will be renovated and restored. Some of the dresses are museum pieces. Several corsets show Frida’s own hand (or the hand of someone close to her) having added a layer of fabric to make them less uncomfortable.

In a temporary exhibition hall adjacent to the main house, there was an array of some of the most beautiful dresses, barbaric corsets, and other contents of that room. One prosthetic leg is on display, complete with a high-buttoned red shoe painted on it by an artist friend. Feathers and glittering beads adorn the eveningwear. Frida created art from her own afflicted body.

The contents of the bathroom, as seen in Iturbide’s stark black and white images, are almost hallucinatory. The bathtub was filled with body braces reminiscent of a scene from the Marquis de Sade, several different types of crutches, and a large poster of Stalin, his hand raised in salute or wave. Three twentieth century white enamel enema cans are lined up on a wall shelf, their dark tubes hanging tangled. A hospital gown type smock looks to be stained with blood or body fluids—or is it paint? The black and white photographs don’t tell us. In one image the empty tub holds only a large tortoise. It is unclear whether it is a work of taxidermy or art piece. A framed poster showing the development of a human embryo is titled “Intra-Uterine Life” and is on display today in another part of the house. A large box bears a label for Demerol, which Frida must have had to ingest regularly. One of her prosthetic legs can also be seen in a picture that makes it the only object in the frame. There were said to have been several of her legs in the bathroom. And in one contrived image, Iturbide photographed her own bare feet (or those of a model) pressed against the white enamel of the tub. The feet are bruised, their toes stubby and curled. The frame includes a view of two simple faucets, a spigot, and a drain with its chain.

What is the importance of contested space? Why did I harbor such a desire to enter that place Diego decided should be closed for ten years following Frida’s death? The dictum was rather like the stipulation writers often make, that their letters or other papers not be opened to the public for a certain number of years. But that condition generally concerns people they may have mentioned, who may still be alive and upset. In Frida’s case, she was already gone. Perhaps Diego, in his grief, wanted to hold onto some vestige of her for a while.

Contested space may hold memory, voice, even such physical residue as pain or shame. Privacy and public display may or may not be oppositional. On our visit to the blue house, my partner Barbara expressed discomfort that so much of this woman’s intimate life was on display, open to the eyes of those who were not close to her in life. I have come to respect Barbara’s sensibility about such issues, and thought about this long and hard. Somehow, though, having seen Frida’s brutally personal self-portraits and read her painfully honest diary, I don’t believe she would have been adverse to this exhibition. Her love of the macabre may have made it entirely appropriate to her.

I am interested in how powerful creative women navigate the time and space they inhabit. Not until very recently has it been socially acceptable for a woman to project herself and her work in such an obvious way, and only now in certain societies and situations. From the time she was a child Frida Kahlo was different. Tiny of stature, she was larger than life—and remains so beyond her death. The famous bathroom is but one area of display, made more interesting perhaps because it was locked for so long.

February 06, 2015