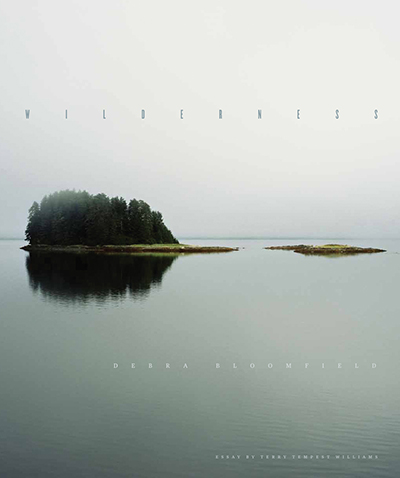

This week we ask photographer and author Debra Bloomfield some questions about her transcendent, exquisitely beautiful book of photographs, essays, and soundscapes entitled Wilderness, which was published by the University of New Mexico Press this year.

New Mexico Mercury: What’s so exciting about this book is the total experience it allows a reader to have with its remarkable conversion of visual, audial, and intellectual experience of wilderness. How did you conceive the possibility of achieving such a total experience?

Debra Bloomfield: I didn’t conceive of it. As an artist, I had questions that I could only come to answer through the experience of making my art. I had no idea that I was sculpting together a book that would encapsulate my seven-year experience and journey into wilderness so completely. Wilderness came to me and unfolded in a very organic way. With each photographical project that I have completed, the initial awareness is a highly emotional and visual response to seeing in a way that I’ve never seen before. It is immediate and all-consuming. This project, however, was ignited by sound.

Debra Bloomfield: I didn’t conceive of it. As an artist, I had questions that I could only come to answer through the experience of making my art. I had no idea that I was sculpting together a book that would encapsulate my seven-year experience and journey into wilderness so completely. Wilderness came to me and unfolded in a very organic way. With each photographical project that I have completed, the initial awareness is a highly emotional and visual response to seeing in a way that I’ve never seen before. It is immediate and all-consuming. This project, however, was ignited by sound.

As I look back at how Wilderness came to be, it all seems very logical. Walking into a forest that I had never been to before, it was the unfamiliar sound deep in the forest that captivated my soul’s full attention. It was the sight and sound of the common raven, the Corvus Corax. As this large black bird sailed out of the tops of the Sitka spruce and over the Western Hemlocks, I knew I couldn’t go home until I understood more about the magic of this wild place.

The one thing that I am committed to in my creative process is staying open. As I moved through this new terrain, my first question was, what is “wilderness”? What are the guidelines for land to be called wilderness? Who protects wilderness? Who threatens wilderness? Who inhabits wilderness? I let the ravens be my guide. In figuring out how I would move through wilderness practically, I acquired the help of a retired federal Fish and Game ranger, Ken, nicknamed Ironman, and his wife, Bev. I am indebted to them both.

I returned six weeks later with my camera and some sound equipment that I’d never used before. I adapted my equipment three times until I finally had something in hand that could collect the complexity of my audible experience.

The intellectual component of this work came together by assembling my questions and looking deeply into their answers. Honestly, I just didn’t sleep for the two years I was in book production.

NMM: As the Sagebrush Rebellion and its call to divest and auction off public lands, including wilderness protected under law, grows in momentum in certain conservative states, your book moves in a completely opposite direction. How did you come to have such positive attitudes about federal land management, a sense that the Mercury shares, by the way?

DB: I simply followed the historical roots of wilderness. This led me to Aldo Leopold and Margret and Olaus Murie. It was their passion for protecting this country’s wild land and their affiliation with the Wilderness Society that led to the passage of the Wilderness Act of 1964. This act designated a national wilderness preservation system to be protected by the federal government. Wilderness needed (and still needs) a federal law to protect it.

It is clear to me that this land cannot be protected properly by private interests that are often profit-driven. We need land that is off-limits and untouchable. It is difficult enough with the four federal agencies that protect wilderness (Bureau of Land Management, U.S. Fish and Wildlife, U.S. Forest Service, and National Park Service) to prevent these lands from being used for the search and transportation of fossil fuels.

Beginning in 1989, when I was working on my Four Corners book, I found refuge with federal park services that gave me valuable information about how best to travel safely into the landscape that was of interest to me. With Wilderness, I have continued to find help from both retired and working federal rangers.

To read more about current debates surrounding the federal stewardship of wild places, see “Rethinking the Wild,” a New York Times article (July 6th, 2014) on how to uphold our responsibility to protect wilderness areas.

NMM: What have been the responses to the immersion experience of fully engaging with this book?

DB: To my surprise, my work has found a new audience among environmentalists, conservationists, and ecologists. My Wilderness work presents a visceral and visual experience of wild places while including the historical and political context. This community understands the lineage and history of what my work is about.

After sitting with my book, my dear friend Terry Tempest Williams wrote to me that I had “articulated something new and very old at once”—that I had somehow accomplished what she called “reflective activism.” This is something I’ve heard said by others in different ways. These words humble me.

At first, the art world didn’t understand what I was assembling. Now, they embrace this work and I am able to join the two worlds of art and science.

NMM: Would you give us some insight into your working relationship with the essayists in Wilderness—Lauren E. Oakes, Rebecca A. Senf, and Terry Tempest Williams—and how they collaborated in creating the end result of the book’s experience?

DB: Lauren Oakes helped me in my studio on Fridays. We had a shared passion in photography, wild places, and our mutual and cherished connection to Terry Tempest Williams. As I was sequencing the images and sound components for the book, I realized that I needed to have an essay for the book that would provide a historical text on wilderness. I wanted to share with my public (at the time thinking only of the art world) the depth and importance of this country’s designated wilderness areas.

Rebecca A. Senf and I met in San Francisco while we were reviewing the work of promising unknown photographers for the Photo Alliance. I invited her for a studio visit and we later met at my hometown gallery, Robert Koch. She looked at my images and later wrote that my work took up residency within her. She has been a profound supporter of this work from the beginning. Wilderness opened at the Phoenix Art Museum in the winter of 2013. I consider Rebecca’s introduction for the book a treasure.

Where does one start to describe or talk about Terry? We have been getting to know one another since my first book, Four Corners, was published in 2004. My then editor Dana Asbury suggested I contact Terry Tempest Williams with the hopes that she could write a poetic essay for my book. It wasn’t until STILL: Oceanscapes, my second book, that we worked together. At the conclusion, Terry said to me that we would have to do this again. When I embarked on my wilderness work, Terry suggested I wander into a particular wood up north. This was where I heard my first raven, though I did not yet know what the sound was. Ravens have fifteen to thirty categories of vocalization dialects. One afternoon she visited me in my studio. She lay down on the floor looking like a snow angel while I played my soundscape and displayed images of wilderness on my walls. After, she stood and said, “Tell me what you want me to write.” My response could only be, “Whatever you want to write will be perfect.” She graced my book with her words. I believe Terry Tempest Williams is synonymous with wilderness.

NMM: While I’m not asking for an “explanation” of the raven, rain, ice, snow, and winter images of the photographs, I think it would interest readers to hear more about your association of the cold, the wet, the windswept, and the airborne with wilderness.

DB: Simply said, I photograph—in whatever weather conditions there are—when I am motivated, inspired, and in passionate pursuit of my work.

Wilderness is available at bookstores or directly from the University of New Mexico Press at www.unmpress.com or 800.249.7737.

Upcoming Author Events for Debra Bloomfield

Saturday, September 27, 2014, 6:00 pm–8:00 pm

Artist Opening Reception

Richard Levy Gallery

514 Central Ave. SW

Albuquerque, NM 87102

505.766.9888

Tuesday, September 30, 2014–Friday, October 24, 2014

Artist Exhibition

Richard Levy Gallery

514 Central Ave. SW

Albuquerque, NM 87102

505.766.9888

Sunday, September 28, 2014, 3:00 pm

Book Talk & Signing

Bookworks

4022 Rio Grande Blvd. NW

Albuquerque, NM 87107

505.344.8139

September 05, 2014