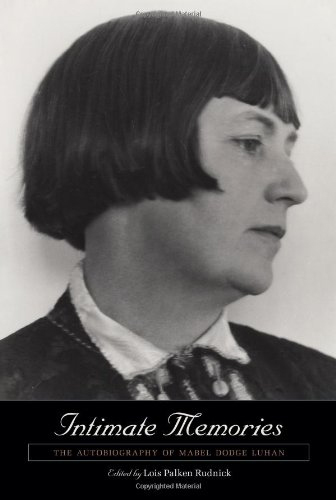

This week we ask editor, scholar, teacher, and writer Lois Palken Rudnick about the reissue of her condensation of the four books of memoirs of Mabel Dodge Luhan, titled Intimate Memories, which make up Luhan’s autobiography. Rudnick’s work as an editor and as a writer of the book’s wisely insightful introduction and afterword gives readers an entry into Luhan’s life and contribution to American culture that has not been possible before. Intimate Memories is published by the University of New Mexico Press.

New Mexico Mercury: How do you account for Mabel Dodge Luhan’s extraordinary candor in these “memories”? And from your perspective as an emeritus professor of American studies, and as someone devoted to studying Luhan’s life and times, was she telling the truth about herself?

I titled my doctoral dissertation on Mabel The Unexpurgated Self just because of the level of candor. But it’s a complex question. Mabel wrote twenty volumes of memoirs, and even though she published some fifteen hundred pages, there were some things she did not want in print until after her death. What is most remarkable about the candor of her published memoirs is her detailed discussions of her manic depression, as it was called then, and her various attempts at suicide to deal with the “abysses” that she would fall into her after one of her manic episodes. She uses the term only once, but her descriptions leave no doubt. And as is true for many manic-depressives, when she was in her manic phase, she thought she could recreate the world—and she did, to a point, in terms of creating extraordinary spaces for writers and artists and reformers.

No autobiographer ever tells anything but her own truth, and that is as true of Mabel as it is of anyone. That said, she allows for a remarkable range of voices throughout her texts, especially “Movers and Shakers,” about her years as the hostess of a radical salon in Greenwich Village that took up every avant-garde cause available, from modern art to birth control to psychoanalysis and anarchism. She writes brilliant word portraits of her closest friends that are often quite accurate. And she is often quite deprecating about herself, because her goal is to show how she symbolized the decadency of western civilization, leading up to her redemption and salvation in the arms of her Indian lover.

She most definitely shows herself at her worst, but she also makes very clear just how really extraordinary she was as a cultural catalyst in many different worlds for many different kinds of creative people. More importantly, her autobiography provides fascinating insights into the worlds she lived in—Gilded Age Buffalo and what it was like to be a poor little rich girl growing up with parents who had no love for each other or for their only child; doyenne of the expatriate community in Florence, which was filled to the brim with fascinating international figures who’d “run away from home” for a variety of reasons; salon hostess and patron of modern arts during her New York years; and, finally, discoverer of beauties of Pueblo Indian life and culture (very romanticized, of course).

NMM: For New Mexicans, Luhan’s “conversion experience” when she first came to our state, an experience which she said broke her life “in two,” resonates on many levels. Despite the dramatic prose of the fourth volume of her memoirs, called Edge of Taos Desert, it leaves us wanting more information. Was there a specific moment in the landscape or at Taos Pueblo around l917 that initiated that great revolution in her life?

Mabel moves her life’s story to the crowning point in Edge of Taos Desert where she reverses the five-hundred-year-old tradition of the Indian captivity narrative by having Tony “save” her from herself and Anglo-civilization. It’s the Christians who are the bad guys in this reversal. She does show this happening slowly over the eight months she covers in the last memoir. But there is the moment of “grace” when she recognizes that she has hurt Tony and he has forgiven her. She even uses that term, which comes from her Protestant upbringing but which she gives a whole new meaning.

However, it’s important to recognize that she ends the story before (presumably) she and Tony are going to consummate their relationship. I paid no attention to that fact until I went to Yale to open up the papers that her son had restricted a few months before I began my forty years of research on her. They are the subject of my last book on her, The Suppressed Memoirs of Mabel Dodge Luhan: Sex, Syphilis, and Psychoanalysis in the Making of Modern American Culture, in which I’ve edited some of the memoirs I wasn’t allowed to see. Mabel had the experience of having confronted venereal disease (VD) throughout her adult life, starting with her first lover in Buffalo (while she was married) and going through three of her four husbands. She finally had symptoms when Tony infected her, some time before or after her marriage to him in April 1923. UNM Press published this book in 2012.

It was astonishing to me, in the decade I researched this subject, the extraordinary impact that VD, especially syphilis, had on western art, culture, film, painting, women’s rights issues, etc. That Mabel could not tell this story, especially about Tony, had much to do with her commitment to Native American rights and culture and to the “bridge between cultures” she believed she and Tony were destined to be.

NMM: What did she mean when she subtitled the Taos volume An Escape to Reality?

Mabel meant that she was leaving the Anglo world—imperialistic, mechanistic, materialistic, individualistic (“like cold flies climbing up the walls of our dying universe” is how she dramatically put it)—for a world that was peaceful, communal, where male and female roles seem balanced and equally respected, where religion, art, and daily living were integrated and not segregated, and where people believed that their rituals and ceremonies helped to keep the world running. Hers was a very romanticized view of that world, and she—and other Anglos like her—has been criticized for this (ad nauseam I would add, given the endless number of repetitive books and essays and doctoral dissertations that have condemned them as cultural imperialists over the past four decades). However, there is little that Mabel said about Pueblo culture (and she never revealed anything “secret,” if she even learned anything she shouldn’t have; Tony kept his lips sealed on the subject of Pueblo religions) that hasn’t been said in similar language by Pueblo scholars and writers like Paula Gunn Allen, Rena Swentzell, and others.

NMM: What do you think was Mabel Dodge Luhan’s greatest contribution to American arts and letters and to American culture? And what was her most admirable personal quality?

Over the past few years, I have been working with a co-curator on a major travelling exhibition titled “Mabel Dodge Luhan & Company: American Moderns and the West,” which will open at the Harwood Museum of Art in May 2016. During this time, I have come across an astonishing number of seemingly endless creative types who were significantly aided in their life’s work by Mabel. I knew a lot about this—it’s the subject of my book Utopian Vistas: The Mabel Dodge Luhan House and the American Counterculture, but over the past twenty years since I really did research on her circle there have been so many new publications of letters, biographies, online blogs, and websites that have increased my knowledge of her reach greatly. Mabel’s two most admirable qualities were her (mostly private) generosity and philanthropy to friends, artists, and ordinary folk in her community who needed her help, whether it was cash, clothes, or giving them a no-or low-cost rental of one of her guest houses. This includes her donations of hundreds if not thousands of books to the Taos Public Library and her donation of the first hospital in Taos, in 1936, as well as the $100,000 she spent to renovate the home she donated and the money she raised by selling “beds” to her famous friends. In terms of broad public impact there is no doubt in my mind, from my years of research, that her creation of “utopian communities” that became home to artists, writers, and reformers from all over the nation and sometimes the world (Willa Cather, D. H. Lawrence, Martha Graham, and Ansel Adams among them) was her greatest contribution to arts and letters and American culture. The fact that her life and character were used again and again as models for the American “New Woman” of the modern era speaks volumes (and there are volumes—novels, plays, poems) about her impact.

NMM: What has the response been to this new release of Intimate Memories? Has it stimulated a greater interest in Luhan as a pioneering Southwesterner focusing on New Mexico’s place in the evolution of American culture?

I honestly can’t say. Intimate Memories was initially published by UNM Press, then dropped under the last press director. I took it to Sunstone Press, who republished it, and it did quite well over the few years they had it. But I disliked their business practices and spent a good deal of money getting my rights back to the book. UNM Press became interested in republishing it (with a slightly revised preface) this past year because it really has lasting value. And it makes a terrific companion piece with my new edition of her “suppressed memoirs.” Few biographers have the good fortune to be able to do two such publications.

Intimate Memories is available at bookstores or directly from the University of New Mexico Press at unmpress.com or 800.249.7737.

February 18, 2015