By Kent Patterson of Frontera Norte Sur

Slightly more than three months after the police shooting of homeless camper James Boyd catapulted Albuquerque into the international spotlight, activists returned to the streets to advance their movement against police brutality.

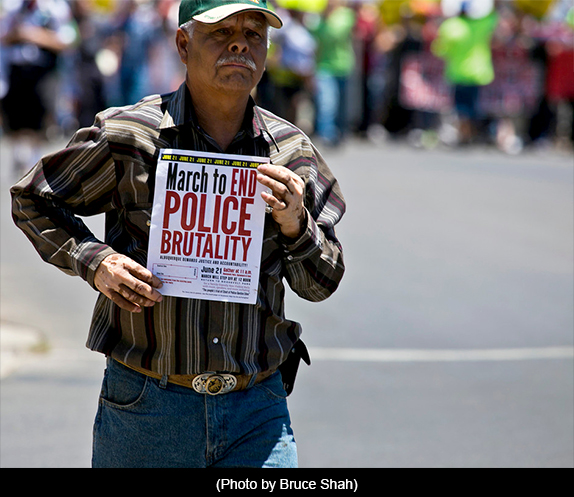

On a blistering Summer Solstice Day, whose blazing mid-day sky was oddly crested by a half-moon, more than 200 people marched up Central Avenue near the University of New Mexico chanting “Justice Now” and “They say justified, we say homicide!”

A big banner titled “Desert Sprits of New Mexico” bore the names of people shot to death by the Albuquerque Police Department (APD), as well as the 11 women and girls found murdered on the city’s West Mesa in 2009 in the largest unsolved crime of New Mexico history. T-shirts and placards remembered the dead: “Justice for Jonathan (Mitchell)” and “In Honor of Alfred Redwine.”

The June 21 protest, which also coincidentally fell on NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden’s birthday, indicated that the Albuquerque battle is evolving into one with national and even international ramifications. Joining the locals, protesters came from Colorado, California and other parts of New Mexico. A young man from northern California, Zac Britton, was among the out-of-towners who came to the Duke City demonstration.

“We’re having the same problems as Albuquerque,” Britton said. “We’ve had 61 people killed in Sonoma County since 2000. We’ve got the U.S. Department of Justice ready to come in.”

Britton said he participated in a June 7 march in Santa Rosa, California, for Andy Lopez, a thirteen-year-old shot to death by local police in 2013. June 7 would have marked Lopez’s 14th birthday, Britton added.

“This is one fight, one struggle. We’re all one big family in this. We’re all in this together,” he said. The Albuquerque march ended at its starting point, Roosevelt Park, where a rally featuring speakers, music, poetry, a “die-in” and a mock trial of APD Chief Gorden Eden extended late into the afternoon. A varied roster of speakers representing family members, activists and others shared different perspectives and personal experiences.

The park was also transformed into a celebratory stage of New Mexico’s rich culture, with Native American rap and traditional song, a blues performance and chants in both Spanish and English emanating from the grounds. Groups participating in the march/rally included La Raza Unida Party, the Albuquerque Center for Peace and Justice, Los Jardines Institute, Brown Berets, Southwest Organizing Project, and others.

Nora Anaya, one of the Albuquerque 13 arrested last June 2 after staging a sit-in at Mayor Richard Berry’s office, told the gathering that she is often asked why she is always crying. The reason is her nephew, George Levi Tachias, who was shot to death by APD back in 1988, she said. “I was a second mother, and I will always cry,” Anaya said.

Anaya, who turned 64 two days before the march and rally, told FNS that she suffers pain in a shoulder and other parts of her body from the June 2 arrest. She blamed the pain on rough treatment by the officers who dumped her into a prisoner transport van.

“I’ve been in shock until four days ago,” Anaya said. Despite the physical problems, Anaya vowed to keep up her activism. “I will not waver,” she said. “If I have to go in a wheel chair, I’ll be there.”

In an interview, the sister of a man shot to death by APD officer James Eichel last March 25 challenged official accounts that her brother was wielding a gun and posed a danger to officers and the public.

Alfred Redwine, who had celebrated his 30th birthday two weeks prior to the fatal encounter, was shot to death only hours after upwards of 1,000 protesters converged on APD headquarters to protest the shooting of James Boyd and other men.

According to Tammy Redwine, who witnessed the shooting of her brother, the West Side confrontation between Alfred and APD began after a dispute with unruly neighbors escalated.

Denying that her brother was armed, Redwine said he only possessed a cell-phone at the time he was shot. The 35-year-old Duke City resident said she had been communicating with Alfred via cell-phone when she was asked by an APD commander to ask her brother to put his cell-phone on the ground.

She said the commander suddenly took her cell-phone away, eliciting a surprised “Why did you do that?” from the woman, before gun shots rang out while Alfred was lowering his hands. Hit three times, Alfred “bled to death” as an ambulance took 20-25 minutes to arrive, according to Redwine. “He would have had at least a 50-50 chance if they would’ve been there sooner,” she contended.

Alfred Redwine’s survivors were traumatized by the sudden end of his life, his sister added. Both of her young sons witnessed the death of their uncle, and the man’s mother heard the fatal encounter over her cell-phone. Since the fateful evening, the boys have suffered nightmares and Redwine’s has had trouble sleeping. “Every night I close my eyes, I hear them gun shots going off,” she said.

Redwine countered portrayals of her brother as a criminal. While acknowledging that Alfred had experienced problems in the past, which his big sister attributed to a meth-using girlfriend, Redwine insisted that he was getting his life together and busily planning a future with a then-five year old son, who turned six three weeks after his dad was shot and killed.

“My brother was an awesome father. Everything he did was for his son,” she said. “My brother was no gang-banger. In fact, he didn’t like gangs.”

Redwine said she was never asked by APD to give a statement, and has not been contacted by either the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ), which has released a highly critical assessment of APD’S use of force practices and is readying a series of reforms for the department, or the office of New Mexico Attorney General Gary King, who told FNS the third week of April that his agency was investigating the Boyd and Redwine shootings.

In April, Albuquerque media outlet KOAT broadcast police-recorded lapel video of the shooting that showed Alfred Redwine holding an object to his head before the shots rang out, but the item in question is not visible as a gun. According to the news channel, the young man had faced several criminal charges in the past.

In an unusual speech, the Roosevelt Park rally was addressed by a speaker with a perspective gained from the inside: retired APD officer Sam Costales, who served a total of 24 years between 1981 and 2009.

Costales characterized many officers as “overzealous,” trigger-happy and disdainful of officers who don’t employ violence.

In comments to FNS, Costales said he first joined APD because he had “always respected the police,” but noticed red flags early on when cadets were taught at the police academy that it was important to stick to a story whether right or wrong and never apologize.

Costales said he was chastised for not using deadly force after a 2001 robbery of the emblematic Dog House eatery, when the APD officer chased down the suspect and drew a bead in on a man who was holding a lead pipe. Costales said he suddenly decided against killing the suspected robber, holstered his gun and subdued the man with mace. A fit 59-year-old, Costales said he would consider rejoining APD if there was a change in the current leadership.

“I wish they’d let me teach at the academy,” he said, adding that his principal lessons would be for the new officers to treat the public “like you want to be, like your family wants to be.” The site of the June 21 rally, Roosevelt Park, has a prominent if officially unrecognized spot in Albuquerque and New Mexico history. A plaque on one end of the hilly and shady place tells visitors that the park is an oasis-like creation of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal of the 1930s.

Designed by landscape architect Edmund “Bud” Hollied, the transformation of an arroyo dumpsite into lush green space put “200 unemployed Albuquerque residents” to work during the Great Depression, the park plaque notes. For generations ever since, Roosevelt Park has been a popular place to picnic and simply hang-out.

Yet there is no plaque to commemorate an event in Roosevelt Park that is intimately connected to the issues raised at the June 21 rally: The June 1971 Albuquerque Rebellion.

The three-day uprising started in Roosevelt Park and spilled out into the surrounding University and Downtown areas following a confrontation between APD and youth.

Richard Moore, co-founder of the Black Berets, an activist Chicano organization that protested police violence and organized the barrios between 1969 and 1973, recalled that the Berets were called on June 13 of 1971 by community members and advised that a confrontation was underway in Roosevelt Park between the police and a large crowd.

Showing up at the park as a chaotic situation unfolded, Moore and other Berets decided to help move elders and children from the scene, as the police were gathering on a hill at the back of the park. In Moore’s account, the Berets attempted to peacefully approach the police with a white handkerchief to signal their intentions. But suddenly the police commenced shooting, forcing the Berets to scramble for cover while one person was hit, Moore said.

“It was like a movie. It was unreal. You could hear the bullets-ching, ching, ching…,” he recalled. “That’s what started the whole thing,” Soon, an enraged crowd was on the streets and a nearby liquor store was the first business to go up in flames when it took direct hits from firebombs. Eventually, the National Guard was dispatched to Albuquerque.

Although the Berets had nothing to do with starting the violence, APD attempted to blame the group for inciting a riot, according to Moore. Ironically, the incident helped expose police surveillance of the activist organization, he said, when the police made comments that they knew the Berets had been making a high number of phone calls all over the city and state in the days preceding the rebellion.

In fact, the Berets had been making numerous calls-to invite people to Moore’s birthday party, the former Black Beret leader chuckled. Nonetheless, the police accusations helped the group confirm that their phones had been tapped, he said.

Now, 43 years later, the latest generation of activists is coping with police surveillance. June 21 organizer Dinah Vargas said she received an unexpected visit at her home by two “well-dressed,” forty-something men on the afternoon of June 18.

Asking to speak to Vargas, the men flashed badges identifying themselves as FBI agents. According to the activist, the visitors told Vargas that they knew she had filed a complaint with the DOJ and wanted to talk to her about that, but quickly changed the subject and said that a call had been received on 311, the alternative emergency line, claiming that Vargas was going “to take someone out” during the June 21 demonstration.

In response to the visit, Vargas said she has filed a public records request to get to the bottom of the false 311 report. Another movement activist, she added, was recently stopped by five APD officers and questioned after leaving a meeting in Roosevelt Park.

The day after the June 21 demonstration, the movement’s Facebook page published photos of a man at the gathering who was identified as an APD officer in plains clothes and accompanied by a group of other similarly-dressed men snapping away pictures.

Vargas said movement activists expect a police presence at their events but “being sneaky” by dispatching undercover officers, especially one who had previously been involved in an officer-involved shooting, at a time when APD is under DOJ scrutiny only reinforces a prevailing community sense that the department can’t be trusted.

As FNS was going to press, a new uproar over APD was spreading across cyber-space because of the undercover surveillance exposure.

The Roosevelt Park rally came at a pivotal moment when the DOJ is expected to hand the City of Albuquerque a list of policing reforms the federal agency wants implemented. The administration of Mayor Richard Berry has hired two consultants, former Cinncinati Police Chief Tom Streicher and ex-ACLU attorney Scott Greenwood, to the tune of $220,000-plus, as negotiators with the DOJ.

On June 12, Mayor Berry, City Council President Ken Sanchez and City Council Vice-President Trudy Jones rolled out “The Albuquerque Collaborative on Police-Community Relations” to “develop sustainable community-policing strategies and plans that ultimately result in widely accepted agreement between the community and the police department,” according to a statement announcing the initiative.

The trio of elected officials said the city was actively seeking input and planning a series of meetings to enact the collaborative, as part of a 6-month process that will include “an action plan designed and built by the community and APD to advance police-community relations, enhance public safety, and address issues that affect quality of life in Albuquerque.”

Until now, Vargas said she wasn’t aware of anyone connected to her movement who had been asked to participate. Whether the collaborative can or will mesh with the positions of the DOJ, which can take the City of Albuquerque to court if is dissatisfied with the city’s response to proposed reforms, is unclear at the moment.

“We could have community involvement, but at the end of the day, it’s Streicher and Greenwood who will negotiate the (DOJ) consent decree,” Vargas observed.

Meantime, activists plan to keep up the pressure in the streets and on other fronts. Tammy Redwine said she has lawyer and is preparing a wrongful lawsuit against the City of Albuquerque for the shooting of her brother. Additionally, she wants the responsible officers fired and indicted. “And I want them to apologize for not having control of the officers in the situation,” she said. “They never gave my brother a chance to surrender.” Redwine said money will not be the purpose of her lawsuit, but another message about police violence needs to be made. “I’m not going to stop until something’s done,” she pledged.

For more photos of the June 21 demonstration:

https://www.facebook.com/pages/Albuquerque-PD-in-Crisis/1434853236758448

June 24, 2014