For Theresa James, the events in Ferguson, Missouri hit home. At a recent Albuquerque solidarity rally for Ferguson residents protesting the police killing of African-American teenager Michael Brown, James spoke to FNS about her own experiences with the Albuquerque Police Department (APD).

In June 2007 the man James called “my best friend” and the father of her two children, 42-year-old Jay Murphy Sr., was shot and killed at his home in the Kirtland Addition neighborhood of Albuquerque by the APD SWAT team during a confrontation following a dispute with a neighbor. Armed with a knife, Murphy had retreated into his home in an agitated state, according to court documents.

The SWAT team stormed a home Murphy had earlier recovered from the City of Albuquerque, after the administration of then-Mayor Martin Chavez red-tagged it as part of a nuisance abatement campaign. In James’ remembrance, SWAT bullets “almost hit my daughter” as Murphy was shot and killed. Years later, the accountant retraced Murphy’s long series of run-ins with APD that included previous SWAT incidents and an alleged police beating before culminating in the fatal stand-off.

James acknowledged that Murphy had drug, depression and PTSD problems, but said his positive side included working with and helping students at West Mesa High School. “When he wasn’t on drugs he was a good, decent person,” she said.

Two days after Murphy’s killing, James was pulled over on the freeway by a “sea of police officers”, detained and accused of intimidating a witness, she added. Questioned by then-APD Detective Michael Fox, James was jailed overnight but eventually saw the charges against her dropped. “They should have never arrested me,” she insisted.

According to the longtime Albuquerque resident, she also had to battle state child protection authorities who wanted to take her children away because of the Murphy incident. “It was hell I had to go through,” James said.

James lost a federal lawsuit for the wrongful death of Murphy against the City of Albuquerque when U.S. Court of Appeals Tenth Circuit Judge Phillip A. Brimmer ruled against her case early last year.

More recently, the Albuquerque resident spoke to the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) officials who were investigating APD for excessive use of force and civil rights violations, only to learn that Washington was not investigating incidents prior to 2009.

With her family still coping with the emotional fallout of Murphy’s violent death, James said she felt an immediate connection when Ferguson grabbed the nation’s attention in August. “I feel those people are getting more traumatized,” she said. “When I saw it, there was fear in my heart for all those folks.”

The scenes from Ferguson-an unarmed man shot by police, protesters on the streets, tear gas, armored vehicles and military-style police squadrons bearing down on demonstrators- recalled the Albuquerque protests against APD’s shooting of homeless camper James Boyd last spring.

Albuquerque and Ferguson have become global news, with media in Great Britain, Mexico and other nations giving the police violence story top coverage while molding impressions and opinions of the United States.

“I have friends in Africa, the Philippines, who are looking at what’s going on here,” James added.

In between Albuquerque and Ferguson, protests erupted against police shootings of Latinos in the California cities of Salinas, Santa Rosa and Half Moon Bay, among other places. In New York City, thousands marched August 23 against the killing of Eric Gardner, who died from a police choke-hold.

Spreading in scope and intensity the mini-uprisings cut far deeper than individual cases of excessive force. In 2014 sharpening contradictions of race, class, domestic and foreign priorities, and democracy- or the real lack of it-are gushing from the trails of the drug war, the War on Terror and multiple cobwebbed corners of U.S. history.

War abroad stands as a historic parallel between contemporary movements against police violence and previous ones of 1960s and 1970s. Back then, the U.S. was waging war in Southeast Asia. Today the nation is at war in Afghanistan, renewing military action in Iraq, poised for military strikes in Syria, and involved in numerous other conflicts across the world.

A big difference between now and then is the bulging pipeline filled with tools of the trade that flows from the Pentagon and other federal agencies to local police departments. Yet, the ability of the U.S. journalists to cover the protests and their root causes- and inform the body politic of vital issues-is becoming more difficult by the day.

Even President Obama, whose administration is under criticism from media organizations for going after whistleblowers and pursuing a subpoena of New York Times reporter James Risen to testify in a court case about a source for a story involving the CIA, recognized the drift after reporters were detained and harassed by police in Ferguson.

The chief executive declared that “police should not be bullying or arresting journalists who are just trying to do their jobs and report to the American people on what they see on the ground…”

While the experiences of reporters in Ferguson, who got a taste of what Mexican journalists have endured for years, represent the crude end in the spectrum of contempt for the press by some law enforcement and government officials, more subtle policies are perhaps undermining press freedom even more. For instance, Albuquerque reporters have been increasingly denied access to stories or simply found it more difficult to obtain public records.

“I don’t know if it’s a trend, but most states, including the state of New Mexico, have an exception for certain law enforcement documents,” said Susan Boe, executive director of the non-profit New Mexico Foundation for Open Government (FOG). “But what happens, that (security exception) gets broad and virtually everything becomes confidential and informants and we have to fight for documents.”

According to Boe, a “bunker mentality” exists among law enforcement officials that documents and police lapel videos should be kept under wraps. Current New Mexico law provides for a $100.00 per day fine for a government agency violating public records law, but enforcing the statue is another question altogether, she said.

“We don’t have enough private lawsuits,” Boe opined. Would a deluge of legal paper make a difference? “I think it would,” she replied.

A persistent question begs: What are officials hiding and to what ends?

In New Mexico, and especially in Albuquerque, the issues spotlighted by Ferguson have lingered all summer long without clear resolution. In July, the City of Albuquerque and U.S. Department of Justice announced an agreement to institute court-enforceable policing reforms centered on eight areas related to a pattern of excessive force identified by DOJ in its findings on APD that were published last spring. But what the reforms-including genuine civilian oversight of law enforcement- will look like and their timeline for implementation are still subject to negotiation.

In August the Albuquerque City Council finally tossed the graveyard dirt on what was essentially the corpse of a previous, criticized police review commission after three members complained it was toothless and resigned earlier this year.

Police militarization, which is now part of the national agenda, was a hot issue in the Duke City even before Ferguson. As a mass protest movement emerged following the police shooting death of homeless camper James Boyd last March, the second change on a list of 39 proposed reforms drafted at an April community forum demanded a halt to militarization.

The third demand read, “We want a police department that investigates crime and makes arrests, not a paramilitary, counter-terrorism force that views the public as a threat.”

But additional controversy was stirred up over the summer when it was announced that APD intended to spend about $350,000 to acquire 350 AR-15 rifles through a third-party vendor. Stephanie Lopez, Albuquerque Police Officers Association president, told KOB News she supported the new arsenal. Lopez cited an incident last year when a man armed with an assault weapon shot and wounded four officers, leading a good part of the police force on a wild Saturday morning chase that shattered the peace of the North Valley and ended with the suspect, ironically named Christopher Chase, shot and killed by APD.

“There is a need to have these weapons on the street and within the department,” Lopez said.

Sue Schuurman, coordinator of the Albuquerque Center for Peace and Justice, had a different view: “We’re trying to demilitarize APD and they’re ordering 350 machine-guns? How is this a trust building measure? I’d rather see that put into training, deescalating our police force.”

At a July meeting in Albuquerque of the New Mexico Law Enforcement Academy Board, the agency responsible for approving statewide officer training standards and issuing and yanking officers’ certifications, several speakers, including Albuquerque residents Barbara Grothus and Kenneth Ellis II, questioned police militarization but received no immediate response from the board members present.

Chaired by Attorney General Gary King, the board includes representatives from New Mexico State University-Carlsbad, the Las Cruces Police Department, several other law enforcement divisions across the state, and the owner of Kaufman’s West, a store that sells police equipment and supplies uniforms to New Mexico law enforcement agencies.

Recent stories by the Associated Press and other New Mexico media report that not only have the big police departments in Albuquerque and Las Cruces been outfitted with military gear, vehicles and weapons courtesy of the Department of Defense’s 1033 Program of military equipment transfers, but so have small agencies in Luna, Valencia and other rural counties as well.

The emergence of a police industrial complex and a revolving door between law enforcement and private industry is a growing if still largely unexplored issue in New Mexico and elsewhere. Like the relationship between the Defense Department and private military contractors, billions in profits from the public till are for the making in the business of policing. Computers, surveillance equipment, lapel video cameras, stun guns, rifles and much more are all manufactured by private companies and sold by intermediaries with a financial stake in a robust trade.

An ABC-Fusion news investigation published on Labor Day weekend revealed an Iraq War-like corruption surfacing in the military transfers, with scores of police departments in 36 states suspended or permanently cut off from the Pentagon pipeline on account of missing weapons, including assault rifles and machine guns, or failures to comply with inventory requirements.

The controversial Maricopa County Sheriff’s Department in Arizona was found to have 11 or 12 missing weapons, mostly pistols, according to the report. In another instance, the now deceased chief of a small Texas town was indicted for selling or pawning military equipment that included a machine gun.

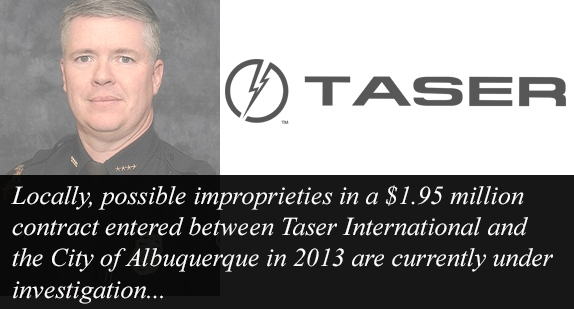

Locally, possible improprieties in a $1.95 million contract entered between Taser International and the City of Albuquerque in 2013 are currently under investigation by the New Mexico Office of the State Auditor in conjunction with the Duke city’s inspector general and internal auditor.

In April, Albuquerque City Councilors Ken Sanchez and Klarissa Pena requested the intervention of the state auditor’s office in letter that expressed concerns about the apparent no-bid contract and the role of Ray Schultz, the former APD chief who emerged as a consultant for Taser shortly after leaving his post last year.

In a written reply to Sanchez and Pena, State Auditor Hector Balderas said he was “concerned by the troubling questions surrounding these transactions and potential violations of state law.”

Evan Blackstone, Balderas’ chief of staff, said the joint investigative review is examining whether there were violations of the State of New Mexico Procurement Code and Governmental Conduct Act. Although months have passed since the so-called Tasergate affair surfaced, Blackstone told FNS that officials were still probing and could not put a specific deadline on a “priority” matter.

“We’re actively engaged in a review of the contract with Taser and some of the concerning questions surrounding the contract and conflicts of interests,” Blackstone assured.

While there has been much talk lately about the transfer of surplus war equipment from the Pentagon to local police departments, especially through the 1033 Program, a recent study by the ACLU found evidence that upwards of one-third of the transferred equipment is of new manufacture.

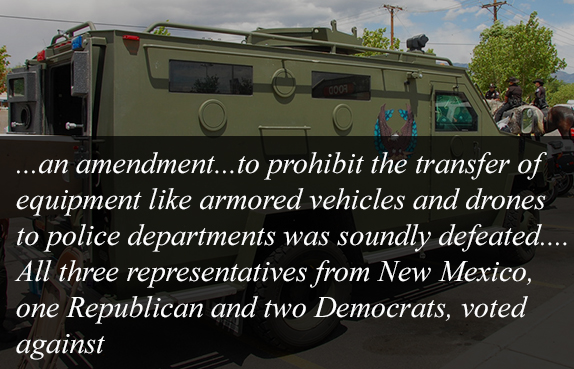

In June, before police militarization became a prominent national issue, an amendment to the House Defense Department appropriations bill sponsored by Congressman Alan Grayson (D-Fla), House Amendment 918, to prohibit the transfer of equipment like armored vehicles and drones to police departments was soundly defeated by a vote of 62-355. All three representatives from New Mexico, one Republican and two Democrats, voted against Grayson’s amendment.

Maplight, a non-profit watchdog organization that tracks money in politics, discovered that only four of the 59 House members who received more than $100,000 in donations from defense industry interests between January 1, 2011 and December 31, 2013 supported Grayson’s unsuccessful amendment.

But after Ferguson, the White House, Missouri Senator Claire McCaskill and Michigan Senator Carl Levin, chair of the Senate Armed Services Committee, are all pledging reviews of the use of military equipment by police departments. In the House, Rep. Hank Johnson (D-GA) is going a step farther with his sponsorship of the Stop Militarizing Law Enforcement Act of 2014, a measure which proposes to “place restrictions and transparency measures” on the 1033 Program.

“Militarizing America’s main streets won’t make us safer, just more fearful and more reticent,” Congressman Johnson contended in a recent statement.

Talk of curbing the 1033 Program has backers like the Fraternal Order of Police (FOP) mobilizing on Capitol Hill, according to The Hill political weekly. In an August 20 op-ed published in USA Today, FOP President Carl Canterbury insisted that military-style equipment was needed for public safety.

“This is especially true for counterdrug, anti-gang or counterterror operations. If police are outgunned and out-armored by gangs or cartels, they are less able to protect the lives of the public,” Canterbury wrote.

The FOP is raising money to defend Darren Wilson, the Ferguson police officer who shot Michael Brown on August 9.

Similar to the 1960s and 1970s, police spying on citizen groups has also reemerged as an issue in the militarization debate. The ongoing practice was exposed at an Albuquerque anti-police brutality rally in Roosevelt Park last June when several undercover APD officers were spotted video-recording protesters. The ACLU of New Mexico has since attempted to obtain the full body of recordings but with limited success.

The department released a few minutes of tape, which mostly focused on Ken Ellis II, a prominent APD critic whose son, Iraq army vet Kenneth Ellis III, was shot and killed by an APD officer in 2010. Later interviewed at another protest, Ellis voiced outrage when asked about the footage released and his starring role in it.

“A three-hour rally and they have five minutes focused on me?” Ellis said, blasting APD for spying on the June rally. “Why even go there? No one’s breaking the law. There’s no civil disobedience. We had our own security there to defuse things,” he added.

A U.S. Army vet who served from 1983 to 1987, Ellis was perturbed by the government’s snooping . “This spying and putting people under surveillance is a pattern they’ve been practicing for years,” he said. “It’s very disheartening. It sickens me to the extent that they would violate peoples’ rights.”

Micah McCoy, communications director for the ACLU of New Mexico, was also skeptical that all the Roosevelt Park footage had been released by APD, adding that several people had witnessed the APD undercover team panning the crowd and directing the camera at rally speakers, who included activists once associated with organizations targeted by the FBI’s old COINTELPRO program, which was essentially a U.S.-style dirty war aimed at destroying social movements.

“We’re always concerned about the scope and overreach of surveillance,” McCoy said. “We’ve been very vocal about the police militarization issue. The nutshell is that our neighborhood is not a war zone and we shouldn’t be treating civilians as an enemy. The police should not be an occupying force,” McCoy said.

In Albuquerque, relatives of APD shooting victims and their supporters took to the streets again on August 27, staging a press conference and rally outside City Hall in protest of the upcoming National Police Shooting Championships, hosted by the NRA and set for September 13-18 in Albuquerque. The event features exhibition space for law enforcement equipment vendors.

Demonstrators held pictures of shooting victims Len Fuentes, Jerry Perea and Jonathan Mitchell, among others, while cut-out gravestones for Mary Hawks, James Boyd and others touched the downtown sidewalk. A placard conveyed the new national slogan of the anti-police violence movement that has arisen from Ferguson: “Hands up, Don’t Shoot.”

Activists rode the elevator to the 11th floor of City Hall hoping to deliver a letter demanding the cancellation of the NRA’s shooting contest to Albuquerque Mayor Richard Berry. Instead, the entourage encountered a locked office entrance blocked by a security guard and Mark Shepherd, the mayor’s security manager.

Shepherd politely told the group that Berry was not in, but promised, “If you have a letter I’d be happy to deliver it.”

“This is what I get for voting for (Berry), for believing in him,” fumed Sylvia Fuentes.

In comments to Shepherd, a visibly angered Mike Gomez, whose son Alan was shot and killed by APD in 2011, objected to the reports of the participation in the shooting championship of APD’s Sean Wallace, the policeman who shot Alan.

“Isn’t it ironic that Albuquerque has the most police shootings per capita and we have a police shooting competition?” quipped Ken Ellis II. “Why don’t we have a de-escalation competition and a crisis intervention to see who could use best their brains?”

In Albuquerque, Ferguson and other places don’t expect the protests to go away anytime soon. The group ABQ Justice plans a demonstration against the NRA’s annual police shooting contest at the Albuquerque Shooting Range Public Park on Saturday morning, September 13.

For more information on the emerging missing military weapons scandal:

http://fusion.net/leadership/story/americas-police-departments-lose-loads-military-issued-weapons-984250

(Photos: Riot police by Dave Herholz, Don’t shoot by Mike Licht, Police caricatures by Donkey Hotey, APD SWAT vehicle by Jim Legans, Jr.)

September 02, 2014