Seldom does a name of a place — Chihuahua — seem to capture so much of its identity and spirit.

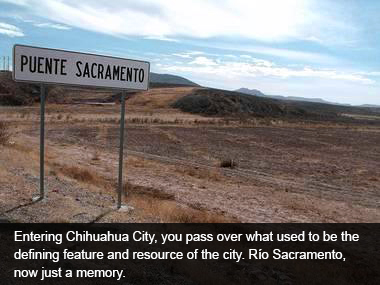

Entering Chihuahua City, you pass over what used to be the defining feature and resource of the city. Río Sacramento, now just a memory.

Perhaps that's due to the name's own expressive rhythm. Or it may have more to do with the many emotions associated with the popular expression, "¡Ah, Chihuahua!," whose beat and varied intonations communicate its different meaning — whether lament, astonishment, surprise, annoyance or dismay.

It's an expression that transcends the border, as do so much of Chihuahua's history, identity, economy and culture — whether in English or Spanish, "¡Ah, Chihuahua!" or simply "¡Chihuahua!"

The name Chihuahua is certainly of pre-Hispanic origin, but its exact derivation is disputed. Some scholars say it's a name linked to the land's lack of water, while others argue that it signifies a place blessed with water.

Dry, Sandy Place

"Xicuahua," a Nátuatl word meaning "dry, sandy place," is the most widely accepted origin of Chihuahua. It's a vast state — Mexico's largest — that is occupied by a desert with the same name. Chihuahua encompasses one-eighth of the nation's land. It's a state larger than many countries, including Great Britain.

The Chihuahuan Desert — the largest and most diverse of North America's four deserts — spreads through the heart of the state, dropping south from southeastern Arizona, New Mexico and West Texas.

Heading south across the border and through Ciudad Juárez, there is nothing but desert. You encounter a vast aridness of mesquite, creosote bushes, tarbush, acacia and occasional tuffs of zacate, mostly trimmed to the ground by starving cattle. (An estimated 400,000 cattle have died on the range during the drought in 2011-12 alone.)

More than 230 miles of desert pass before the toll road approaches Chihuahua City, the state's capital. In the early 18th century the Spanish founded Santa Fe Real de Chihuahua, a villa that served as the midway point along the Camino Real between the rich mine of Hidalgo del Parral in the southwest and El Paso del Norte.

Although Spanish explorers had first passed through the northern territory that is now Chihuahua in 1528, it wasn't until two centuries later that the Spanish and Criollo elite began to settle in the region, drawn by the silver and gold mines in the Sierra Madre Occidental. In the 1700s, the outpost of Chihuahua functioned largely as an administrative center for the region's mines.

The Chihuahuan Desert envelops the city, extending south into Durango and east throughout Coahuila and edging into Nuevo Leon. In the state's southeast corner lies a barren and barely populated expanse sometimes called the Zona del Silencio.

In many ways, the absence of water and the resulting harshness of the terrain seem to define Chihuahua. Aridness is its essence, and the struggle to survive in this stark land may help explain the reputation of Chihuahuenses — their determination, independence, pride and infectious appreciation of life.

When the dust blows, when the sun parches, and when not a single tree breaks the horizon in any direction, Chihuahua certainly seems nothing but a dry, sandy, uninhabitable land — an unending, oppressive aridness.

Where Rivers Meet

But there is another way to see Chihuahua: looking beyond the aridness to see how much the state is shaped and defined by the power, presence and fundamental importance of water.

Tarahumara women gather in front of the Palacio de Gobierno in Chihuahua City as part of campaign to save their land and water from a government-sponsored megatourism project in the Sierra Tarahumara in southwestern Chihuahua.

There are many who say Chihuahua's name has more to do with water than desert. Before there was the territory, city or state of Chihuahua, there were native Rarámuris or Tarahumaras living at the intersection of two rivers, the Sacramento and the Chuvíscar. When the Spanish moved in, they adopted a variation of the indigenous phrase meaning "the place where two rivers meet."

No longer do these two rivers meet in Chihuahua. Only the sandy and gravel-strewn beds of the Sacramento and Chuvíscar remain — the rivers now running only immediately after torrential downpours during the summer's monsoons.

Recent summer rains have lifted spirits in Chihuahua and watered near-empty reservoirs. But prevailing trends of climate-change-aggravated drought and the disappearance of deep aquifers challenge the future sustainability of the state's cities and rural economies.

Where there are (or once were) rivers in Chihuahua, there are also corridors and centers of human life. In the north, the Rio Bravo/Rio Grande separates Chihuahua from Texas, while the Rio Conchos (which runs southwest from the border town of Ojinaga) is that river's largest tributary.

You don't, however, need to spend much time in Chihuahua to recognize that its life depends on the sierras. A third of Chihuahua is mountainous, and no other Mexican state has so much forested land. The melting snow and rainwater, which come rushing and seeping down from the mountains into the grasslands and desert valleys, have made Chihuahua habitable.

Drug Wars and Water Wars

Over the past six years, no other state has been so closely associated with the horrors and the intensity of the drug-war violence of Mexico. For most people not from Chihuahua, whether inside or outside Mexico, the images and numbers of the drug wars have come to define Chihuahua.

In Chihuahua, you often hear the charge that the foreign media and the State Department have colluded to paint a misleading picture of a land besieged by crime, a type of "failed state." In fact, locals assert, for most people, particularly those not involved in the drug trade and other organized crime, life has gone much as usual.

Yet there is no disputing the graphic images of tortured victims and numbers of dead that have given the state's largest city the reputation as the world's murder capital. The tens of thousands of Chihuahua residents who have fled the state are also testament to high levels of violence and fear that have swept across the state like a desert dust storm that blasts all in its path.

For whatever combination of factors (including the resolution of inter-cartel conflict, the decrease in social cleansing carried out by government and organized crime elements, and cyclical shift in pattern of crime), the drug-war related violence has diminished considerably over the last couple of years in Chihuahua, most notably in the epicenter Ciudad Juárez.

There is widespread hope in Chihuahua that the state has seen the worst of the drug wars — a hope engendered not only by the falling murder rates in Juárez but also by the end of the Felipe Calderón sexenio. Many believed that that his successor as president, Enrique Peña Nieto, and the PRI would engineer a truce among the cartels or somehow end the drug wars, perhaps by ending the military's central role in the drug war or by reorganizing and reconstituting the federal, state, and local police.

Drug-related violence has somewhat subsided in Juárez and Chihuahua City, bringing these cities back to life, although fear and pessimism rise after occasional spikes that rival the worst days of the Calderón years. Meanwhile, criminal bands associated with drug production and trafficking continue to ravage many parts of the state, highlighted by the assassination of a journalist in the border city of Ojinaga and the murder of a mayoral candidate in the southwest.

As drought persists and water reserves shrink, the drug-war crisis has been increasingly overshadowed by the rising fears about water supplies and by escalating battles over access to the state's diminishing reserves. (See The Coming Water Wars, April.)

Wherever one travels — through the heart of the great desert, past the parched and rapidly disappearing grasslands, into the sierra, and off the traffic corridors into the colonias of the capital city and Juárez — life in Chihuahua is threatened. The essential aridness that has defined the region — giving rise to the Páquime civilization a thousand years ago and birthing the Mexican Revolution a hundred years ago — is threatened by a still greater aridness that is marked by higher temperatures, more severe droughts, and rapidly depleting aquifers.

September 04, 2013