Paper art is said to have originated over a thousand years ago in Japan, but it has been practiced in one way or another in every era and almost every part of the world. It can be extraordinarily sophisticated, the final product resembling a complex three-dimensional sculpture or even a walk-in construction in the most prestigious gallery or museum. It can be rudimentary as in a vase of paper flowers in a waiting room or gracing a tombstone in the most nondescript cemetery. It can be simple or complex, ephemeral or preserved under glass. Much contemporary paper art is linked to artist books, from the extensively modified volumes that become extravagant scenes in the hands of the world’s most illustrious book artists all the way to magical examples of mass-produced children’s pop-ups.

Papel picado is in a class by itself. It may combine innovative design with longtime traditions of popular culture. In its traditional form it exists outside the parameters of art galleries and museums; in its most innovative examples it has become a genre as interesting as wood, metal, clay or the painted canvass. Because of this versatility, it is as suited to conveying popular myth and adorning traditional cultural events as it is to being featured in an exhibition like the one described here.

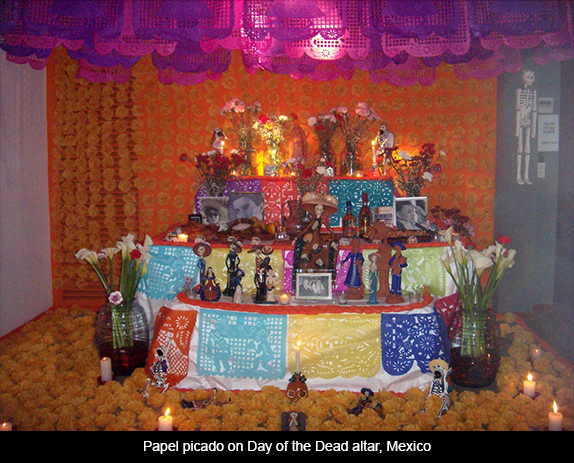

The beautiful Mexican tradition of papel picado, those oblong swatches of brightly colored tissue paper cut into intricate designs that festoon street fairs and altars like prayer flags south of the border, morphs into four distinct artistic styles at one of the National Hispanic Cultural Center’s current exhibitions (up through the end of January, hours Tuesday through Friday 10 to 5, Saturday 8 to 3, and Sunday 9 to 3). The four women artists featured—Catalina Delgado Trunk, Josephine “Josie” Mohr, Cay García, and Kai Margarida-Ramírez—were born over a 40-year period, thus embodying visions spanning almost two generations. Each has imprinted the medium with her unique voice, and the work of each is magnificent.

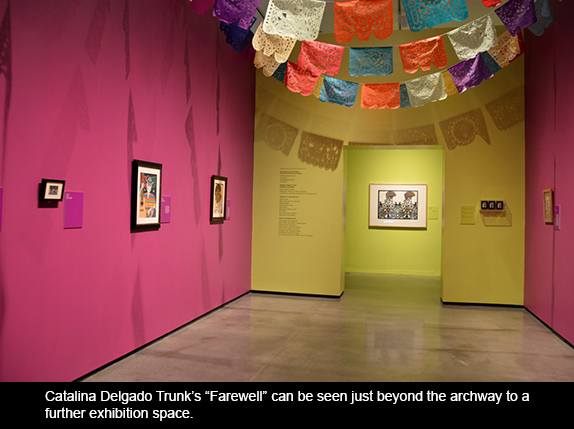

The National Hispanic Cultural Center’s beautifully organized galleries can always be counted on for exciting shows. Currently, aside from some exquisite examples out of the institution’s permanent collection, AfroBrasil: Art and Identities shares space with “Papel! Pico, Rico y Chico.” The former opened in December 2014 and will run through mid-August 2015. The latter opened in June 2014 and will close on January 31, 2015. I urge those who haven’t yet visited to make sure they do.

NHCC has hosted a number of exhibitions that explore art forms in the Latin American/Hispanic/Chicano/New Mexican traditions. I think especially of a gem-like collection of huipiles (hand woven and embroidered regional women’s shifts from Guatemala and Mexico) and the powerful Chicano posters that impacted viewers a couple of years back. Since Tey Marianna Nunn came on board as director and chief curator of the art museum and visual arts program, consistency in coherence and quality have been ever more evident.

Nunn speaks of this paper art’s origins and cultural significance: “An ephemeral genre of popular art, papel picado (cut, perforated or punched paper) is best known as a traditional Mexican art form. [It] is typically used to festoon celebrations, altares, churches, and other public or devotional spaces in Mexico. It is not unusual to see strings of papel picado banners crisscrossing local streets in big cities and small towns throughout that country. These banderas are made of tissue paper (and nowadays some in plastic!) and almost always disintegrate as they fall subject to weather and other environmental elements. […] Using a popular or ‘folk’ art form and re-contextualizing it to represent contemporary identity and fluidity thereof is one of the recognized characteristics of Hispano, Chicano, and Latino art.”

I would also mention the negative space aspect of the art form. The fact that the image is most often achieved through a cutting away of the paper—the see-through areas that are left allowing us to view landscape, people, and movement as well as what may be glimpsed beyond what has been removed—imbues the work in a variety of possibilities. As in life itself, layering accrues to the artist’s advantage.

Born in Mexico City in 1945, Catalina Delgado Trunk now lives in Albuquerque. She is the oldest artist in the show. She sees the traditional art form as “a metaphor for life, ephemeral and traditional, yet evolving as it meets new needs and challenges.” Some of her images harken back to the powerful Taller de Gráfica Popular founded in Mexico in 1937 by Leopoldo Méndez, Pablo O’Higgins and Luis Arenal, or evoke José Guadalupe Posada’s figures from the era of the Mexican revolution, when the dancing skeleton might wield a rifle in defense of the impoverished masses.

Delgado Trunk’s pieces are more everyday and intimate than that of these forebears, conveying a woman’s sensibility in intricate and fanciful scenes that reflect home, hearth, the long suffering of women’s role, and a strain of humor. Her wonderful “Farewell” delights us with two skeletons on bicycles, their heads laden with whatever we may imagine as they ride through a bed of flowers and animals. The gallery devoted to Delgado Trunk’s participation in this show is a magical space.

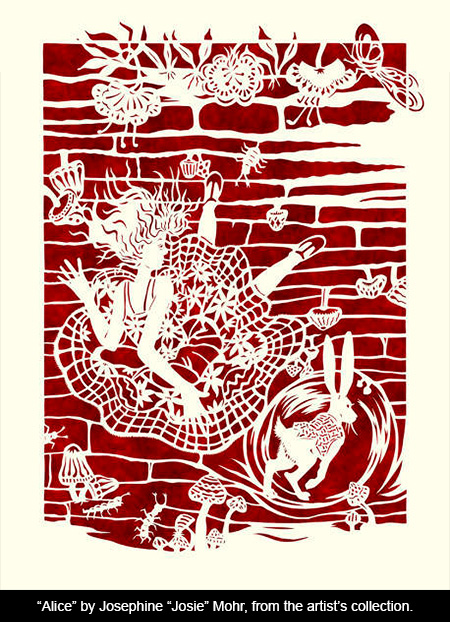

Next in age is Josephine “Josie” Mohr, born in Los Alamos in 1953 and now living in Albuquerque. In her artist’s statement she explains that her fascination with cut paper started one Christmas: “I was attempting to cut a snowflake for the holidays. I thought it was just alright. My other half (Mike) suggested that I do a paper cut ‘snowflake’ of our 5-foot long iguana named Snidely Whiplash. Now this was a square piece of paper that I folded in half, then in half again, etc. – just like in elementary school. I lightly sketched Snidely and began to cut with giant (well – regularly sized) scissors and Snidely turned out beautiful. It was then that I realized I loved the stark contrast of black and white – bold imagery telling a story. This became an obsession with me—showing depth, shadows, and emotion using one color to tell the story and the background to hold it all together.”

Biographies of each artist and their personal statements are incorporated into this show not in the conventional plaques but in large wall lettering that compliments the work itself. One can move from words to images and back again, gaining a profound feel for each artist’s history, vision, and work method.

Although all four artists are storytellers, Mohr’s images most graphically depict folk legends and fairy tales, cut (quite literally) from her unique rendering of their iconic characters. Her pieces cross regional and national frontiers, and hold a knowledge shared by peoples in many cultures. Typical of her playful subjects is “Alice,” in which Lewis Carol’s instantly recognizable protagonist is falling through the rabbit hole, her swirling skirt almost a commentary on Marilyn Monroe’s famous air-blown version.

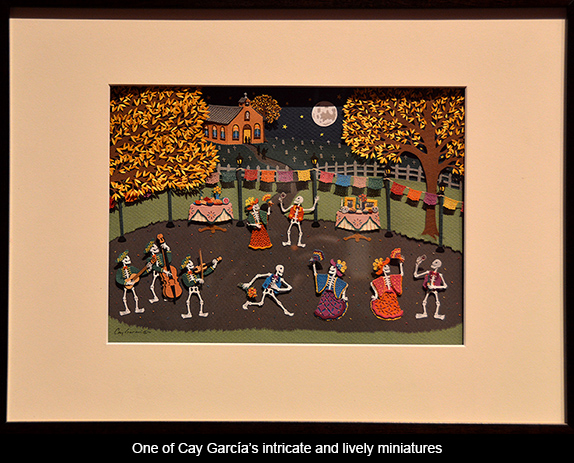

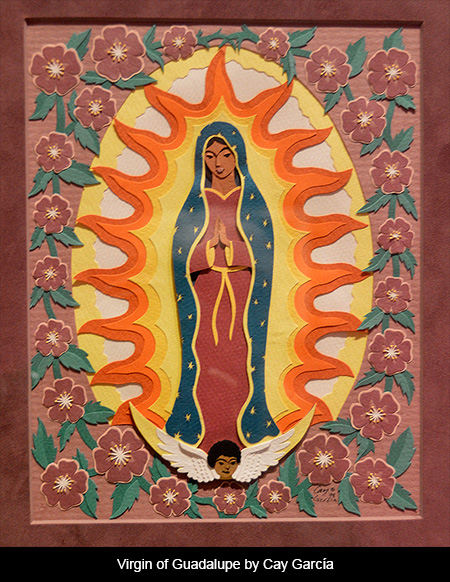

Cay García was born in Albuquerque in 1969, and continues to live and work in her native city. Her bold and colorful work has included scenes from Rudolfo Anaya’s Bless Me, Ultima, local Santos and Matachines traditions, Día de los Muertos iconography, and the Virgin of Guadalupe. But she also draws on Near Eastern traditions (she holds a degree in Near Eastern History).

For García’s larger layered pieces, her process is to first sketch, trace, and then photocopy her patterns, and she also uses collage. “False Modesty,” in which a coquettish woman peeks over a stylized fan, was one of my favorites. Some of her works are assembled from more than one hundred separate pieces. Her miniature scenes, involving perspective, shadow, and trees with miniscule leaves, are breathtaking.

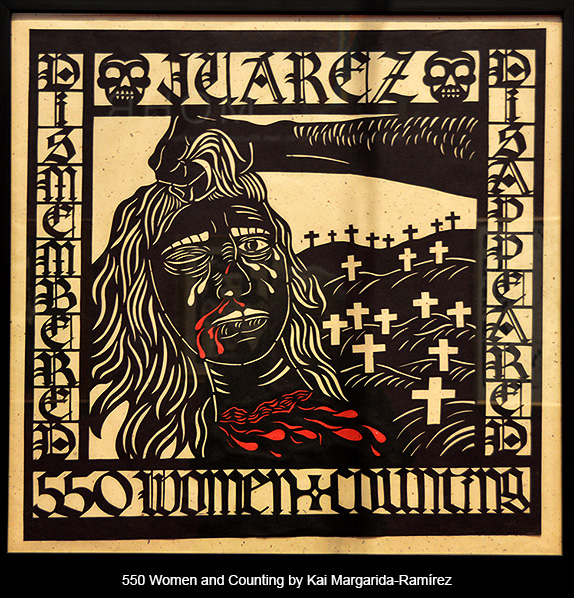

Kai Margarida-Ramírez, originally from Puerto Rico, raised in Albuquerque and now living in Brooklyn, is the youngest of these paper artists. She was born in 1985. She describes her work as post-colonial, feminist, and conscious of border issues. Her critiques of gender and identity are powerfully contemporary. Several of her sophisticated pieces are imbued with a biting humor or irony, like those that include phrases such as “Thank you for the STD,” “I cheated on you too” and “Cheap bastard.” Others frame body parts—a leg, a hand or foot—reminiscent of the Milagros one often sees at holy healing sites. The masked Mexican wrestler, El Santo, is also featured among her contributions to the exhibit.

One of my favorites of Margarida-Ramírez’ pieces is allusive to the murders of the women in Juárez. Splatters of red blood can be seen on the face and breast of a woman’s head in the grip of a man’s arm in brutal gesture, crosses recede on the picture plane, and “550 women and counting” is inscribed along the bottom of an image that also draws on the woodblock aspect of Taller Gráfica tradition.

Another of Margarida-Ramírez’ images stopped me in my tracks. For me, it was the most powerful piece in the show. One of its largest pieces, it places fragments of a screen in a pattern reminiscent of Islamic design over parts of an old family photograph in which several women assume a variety of poses. In this image the artist creates a new intersection of genres, using it to express the tension between how women are repressed and how we move through and out of that repression: an extremely successful example of unity in form and content.

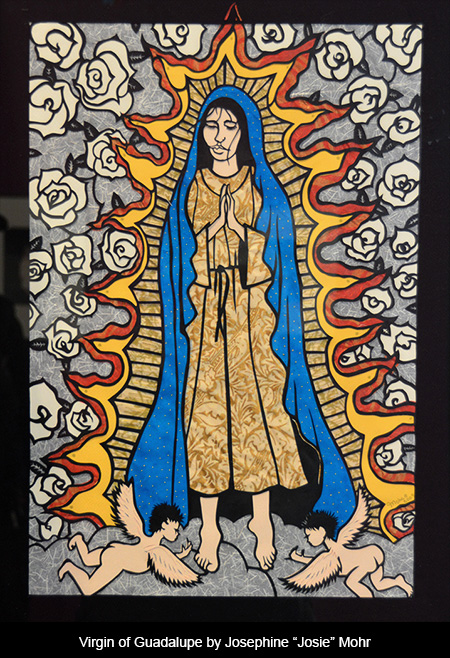

One would expect to find Our Lady of Guadalupe, the Virgin of preference for poor Latina women, represented in an exhibition such as this one. Two beautiful images oblige. Each, in a different way, depicts the Virgin imagined by the artist who created the work. Guadalupe, who appeared to illiterate peasant Juan Diego in December of 1531, is revered in the Mexico City basilica bearing her name and throughout the Spanish-speaking world. For the impoverished Mexican masses she replaced the whiter more elegant Virgins imported from and imposed by Spain. Today she continues to speak to women who shower her with their devotion. “Josie” Mohr’s and Cay García’s Guadalupes are very much women’s images, bringing a female sensibility to a subject that has been portrayed in many different ways.

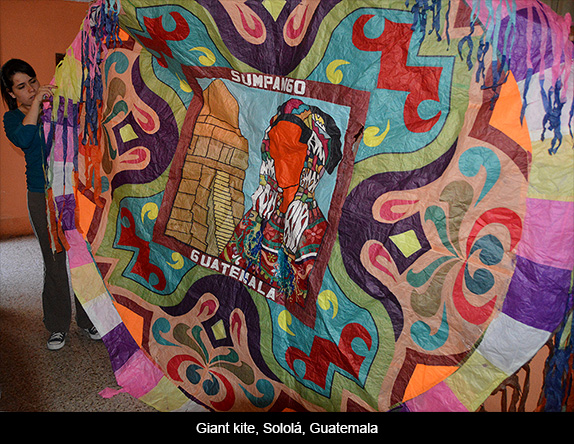

Paper art exists throughout the world in a variety of forms. Along with the cutout variety, there are lanterns, kites, and many other examples. The one of a kind production by a world-class artist and mass-produced decoration blend almost seamlessly. Paper is cheap and plentiful everywhere, and its impermanence is amply made up for by the genius that shapes it.

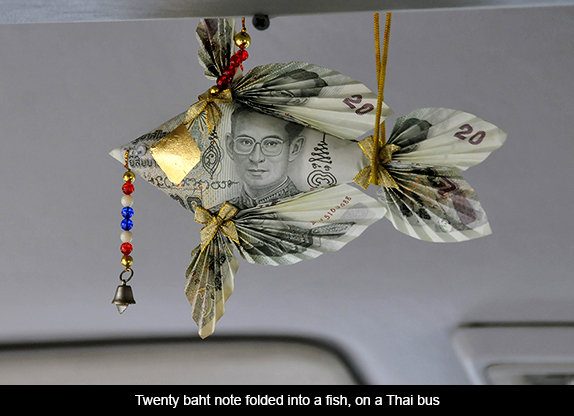

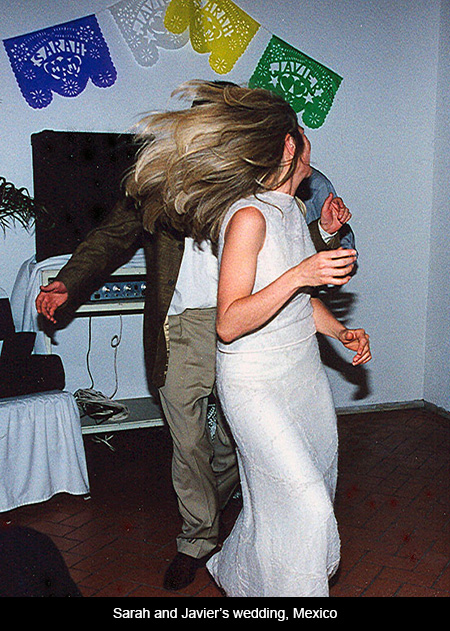

I think particularly of the giant kites I saw in Sololá, Guatemala, on which political demands were applied to an ancient artistic tradition. I remember the large paper lanterns we released into the night sky in northern Thailand, carrying our fervent wishes as they drifted upward and burned smaller. I was intrigued by the 20 baht notes folded into birds and other ornaments in honor of the Thai king’s birthday. And, in my own family photo album, I found pictures of my daughter Sarah’s Mexican wedding to Javier, at which traditional swatches of papel picado bearing each of their names adorned the walls.

January 15, 2015