I am proceeding very slowly, nature appears to me very complex; and the road is never ending.

Paul Cezanne to Emile Bernard

Aix-en-Provence,

May 12, 1904[1]

At seventy-three I was somewhat able to fathom the growth of plants and trees, and the structure of birds, animals, insects, and fish. Thus when I reach eighty years I hope to have made increasing progress and at ninety to see further into the underlying principles of things so that at one hundred years I will have achieved a divine state in my art and at one hundred and ten every dot and stroke will be as though alive.

Gykyo Rojin Manji (Katsushika Hokusai’s last name change)[2]

But one has to feel beyond them into the roots and into the earth itself. One has to be able at every moment to place one’s hand on the earth like the first human being.

Rainer Maria Rilke to his wife, Clara Westhoff

Paris VIe, 29, Rue Casette,

Sunday afternoon, October 20, 1907[3]

To the Tewa speaking people of the northern Rio Grande the mountain is Oku Piñ, Turtle Mountain, and from the vantage point above the La Bajada escarpment, the metaphor is easy to see, with the head stretching out to the west from beneath a large hump which arcs toward the sky. Sacred to war, it is the southern marker in the Tewa cosmos, the South World Mountain, home of Oku-wa-piñ, father of the twin War Gods and Wa-kwijo, Mother of the Winds. Edgar Hewett, the first director of the Museum of New Mexico in Santa Fe, called it “the Mount Olympus of the Southwest.”[4] The Tiwa speaking people who live along the river west of the northern end of the mountain in the pueblo called Tuf Shur Tia, Green Reed Place,[5] call it Posu gai hoo-oo, “where water slides down arroyo,”[6] probably noting both its life-giving power that supports their agriculture in the valley as well as the flash floods that come down from the summer rainstorms. There are said to be shrines that are still venerated up in remote places on the western face of the mountain. To the Hispanic settlers who came together to form La Villa de Alburquerque in the early 18th century, they became known as Las Montañas de las Sandias, the Watermelon Mountains, from the pink glow on the granite of the western escarpment that hovers over the valley shortly before sunset. Geologists will tell students that the Sandias are not part of the Rocky Mountain chain, but an uplift fault in the rift valley of the Middle Rio Grande watershed. As a young boy, I grew up knowing them simply as “the Sandias,” hiking the trails of the western side and running through the arroyos of the East Mesa that incline down to the river. To the visitor approaching the mountain by car from the east on I-40, the hunched, rounded shoulders of the mountain give no hint of what lies beyond, but as one comes through the pass of Tijeras Canyon, the mountain spreads out to the north, and the valley spreads open below. Coming from the west on the same interstate, the Sandias form a magnificent backdrop behind the city of Albuquerque as one comes over Nine Mile Hill.

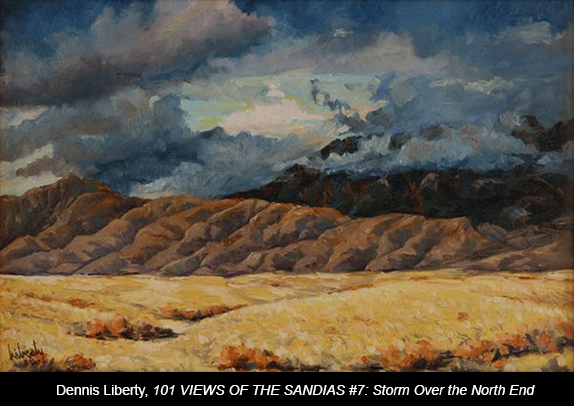

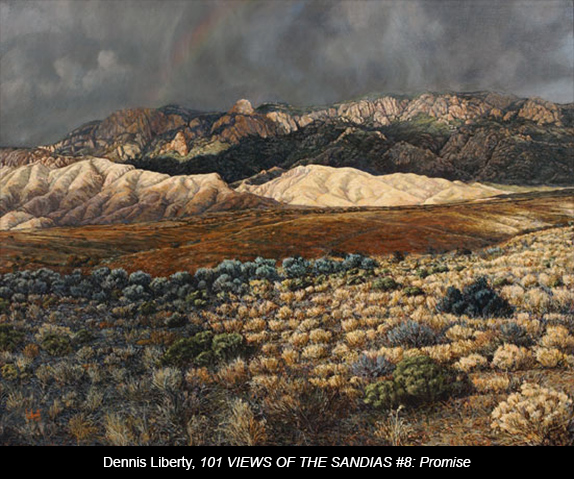

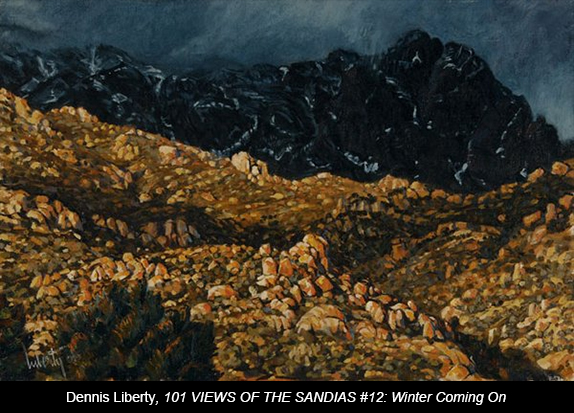

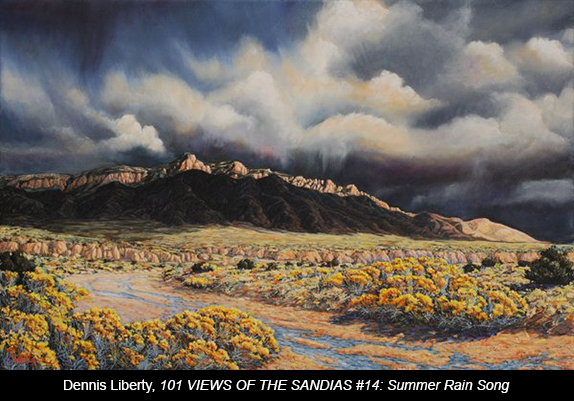

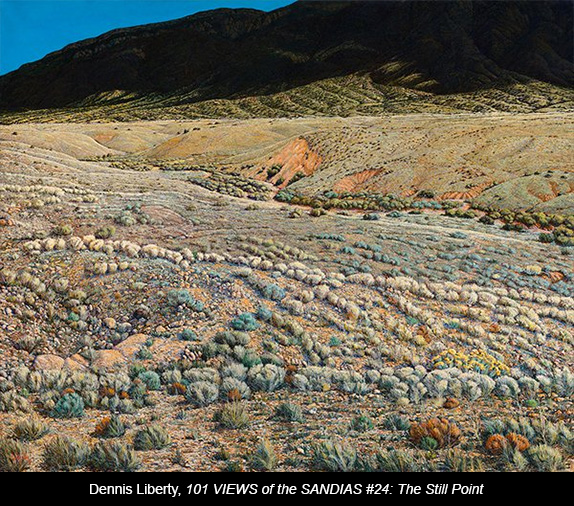

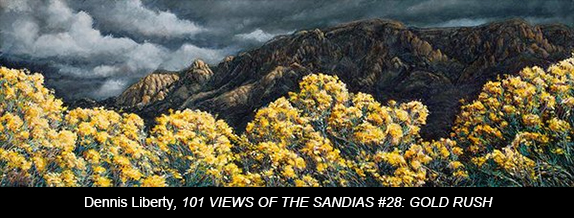

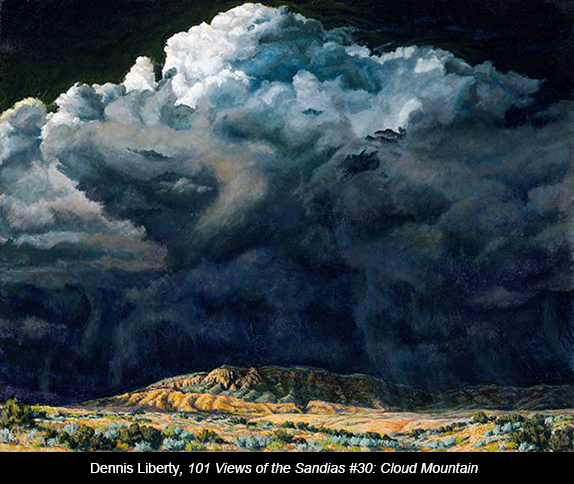

In 1969, after traveling the world as the son of a Navy captain, Dennis Liberty found his home in the valley below the Sandias. An artist of many skills—sculptor, jeweler, woodcarver, photographer—he has settled into the solitary life of the painter in his studio. Books and music, the smells of oil and turpentine, and the thoughts of what it means to make works of art out of images of light and shadow. It took Dennis a long time to decide to paint the mountains that were right in front of him. Too imposing? A cliché? Only a few others had done it and done it well. When Ernest Blumenshein moved down from Taos to Albuquerque he took up the challenge of painting the Sandias occasionally in the 1940s as he looked across the spreading mesa from a vantage point at the top of the sandhills that define the eastern edge of the Rio Grande floodplain. But more often he cast his gaze closer to his home at the Alvarado Hotel, drawing the geometric patterns of the downtown buildings or the trains in the rail yards. Albuquerque’s own Wilson Hurley, lawyer turned fighter pilot, turned artist, embraced the Sandias as heroic drama just as he did the Grand Canyon and many other Western vistas. He lived at the base of the Sandias, watching the light change as the clouds passed overhead. In their heroic scope and grandeur, his paintings sought to give these mountains a national significance, like the 19th century paintings of Albert Bierstadt in Yosemite or Thomas Moran at the Grand Canyon, but with a keen interest in the applications of modern science to art.[7] Dennis’ view of the Sandias is different.

Like most professional artists of his generation, Dennis is the product of a university education and, like all such students, he has grappled with the rarified atmosphere of modernist aesthetics and the reductive trajectories of non-objective painting. However, he has found that purely non-objective painting cannot sustain his interest and consequently, like many others, he has turned to the landscape in front of him. In this, he is less interested in the grand historical visions of the late 19th century American painters and more attuned to the simple pleasures found in nature by the Impressionist and Post-Impressionist painters and the Japanese painters that inspired them. And, like those artists, Dennis has begun to work in series. Cezanne saw Mont Saint Victoire as a constant presence and painted it many times. Hokusai looked at Mt. Fuji, and felt that Edo’s iconic symbol would require many views to reveal its essence.[8] The Sandias became the same kind of presence for Dennis and so he began to photograph and paint them.[9] Over time, as he became more comfortable with the mountain, its imposing mass and deep history faded from his thoughts; like Cezanne, he saw the mountain as a motif, a means to make a painting. But Dennis does not paint painstakingly from nature, as did Cezanne; he is not trying to recreate what the eye sees, those precise color relations that fit what Cezanne called his petite sensation. Dennis does not struggle with the fleeting moment of perception.

And unlike Hokusai, whose Mt. Fuji is set against a constantly changing welter of human activity, Dennis’ paintings of the Sandias reveal no human presence. Although the Middle Rio Grande Valley is home to half a million people who work and live here, their activity, and the built environment that sustains them, is never seen. The transmission towers that stand out so prominently at the crest are not there. The mountain does not constitute a constant presence amid the flow of human activity but is itself always changing, as Dennis’ point of view changes, as weather comes and goes, as light glows and fades. Dennis moves around the mountain as it were, to the left, to the right, now closer, now retreating to a comfortable distance, like a vigilant boxer, looking for an opening. When one of those openings speaks to him, he moves to the studio, where the work of making the painting begins. There, the image that was once in the eye becomes the painting and the painting takes on a life of its own, growing slowly. One is reminded of Matisse’s comment that “Perhaps I might be satisfied momentarily with a work finished at one sitting but I would soon get bored looking at it; therefore, I prefer to continue working on it so that later I might recognize it as a work of my mind.”[10]

So these paintings are, at one level, abstractions, creations of the mind as it works its way over the canvas. In keeping with modernist sensibility, most are titled with numbers, reinforcing both that sense of abstraction and the practice of working in series. Occasionally, a title will hint at history and human presence, but it is like an apparition that is fleeting and imaginary, like something seen and missed. Coronado’s Gold is such a title: poignant, and evocative of historical memory. The first conquistador and his company made their winter quarters in this valley in 1540, and certainly he saw the autumn yellow expanse of chamisa on the mesa below the mountains, but searching for gold of a different kind, he moved on, only to find disappointment. The truth, and true treasure, can be right in front of you, yet not recognized.

The truth of the painting is that it does not on the one hand pretend to be other than what it is, a painting, yet on the other, it does pretend to be “true to life.” This may seem a paradox, but the resolution is that while these may be thought of as “mountain paintings,” or “paintings of the Sandias,” they are ultimately, simply paintings. This is true in much descriptive writing as well, and our language reinforces it. “Nouns always trump adjectives, and in the phrase ‘historical fiction,’ it is important to remember which of the two words is which.”[11] Dennis is, in one sense, like a good fiction writer, who creates a setting so compelling in its feeling and emotion that, although it is not a literal recreation of the visual field, it is a presence that is altogether convincing in that it seems like the truth. In this, like many other painters of his generation who look at the real world, he is aware of Picasso’s famous comment, “We all know that Art is not truth. Art is a lie that makes us realize truth, at least the truth that is given us to understand.”[12] The purpose of these paintings of the ever-changing appearances of the Sandias is to press for a timeless truth behind those appearances and it can only do this by stimulating the imagination and moving the emotions. The paintings are not simply cognitive records of what Dennis saw, nor are they records of what you might have seen at one time; it is not enough to simply say “Yes, I recognize these mountains. They’re the Sandias.”[13] We are moved instead to say, “Yes, this is the mountain I know,” and “knowing” takes us beyond any particular moment.

When looking at these paintings we know that this is the mountain that we know, yet we have never seen it like this. It is as if we are seeing something familiar but seeing it for the first time. With all human presence edited out in the process of painting, these are not “views” in the conventional sense. They are not what we see from Albuquerque if we were to look out to the east today. The mountain in the paintings could be the mountain at the time of the Pleistocene/Holocene boundary, before any historic human activity has encroached on it or given it significance.[14] Like Rilke looking at Cezanne’s paintings of Mont San Victoire, we are “feeling beyond” these mountains and “into the earth itself.” We see the Sandias through Dennis’ mind and it is as if we are the first human being to see them.

[1]John Rewald, ed. Paul Cezanne Letters. Translated by Seymour Hacker. Revised and Augmented Edition. New York: Hacker Art Books, 1984, p. 297.

[2] Henry D. Smith, II, Hokusai: One Hundred Views of Mt. Fuji. New York: George Braziller, Inc. 1988.

[3] Rainer Maria Rilke, Letters on Cezanne. Translated by Joel Agee. New York: North Point Press, 2002, p. 65.

[4] Edgar L. Hewett, Ancient Life in the American Southwest. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1930, p. 97

[5] “Pueblo of Sandia History.” Sandia Pueblo Website, Pueblo of Sandia, 2006. Retrieved on 1/29/2009.

[6] T. M. Pearce, New Mexico place names; a geographical dictionary. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1930, p. 143.

[7] Hurley was initially trained in engineering. He did use photographs as memory aids and substitutes for detailed sketches, but did not work directly from them. See Peter H. Hassrick and James Forrest, Wilson Hurley: A Retrospective Exhibition. Kansas City: Lowell Press, in association with The Albuquerque Museum and the Buffalo Bill Historical Center, 1985, pp. 38, 42-43 and passim.

[8] Late in his life, between 1826 and 1833, Katsushika Hokusai published Thirty-Six Views of Mt. Fuji; this series of color woodblock prints actually came to total 46 views. This was followed in 1834 by One Hundred Views of Mt. Fuji, a publication of black-and-white prints in book form. His younger rival, Ando Hiroshige, also worked in series, the best-known being 53 Stages on the Tōkaidō and One Hundred Views of Edo. See Henry D. Smith, II, Hokusai: One Hundred Views of Mt. Fuji. New York: George Braziller, Inc. 1988.

[9] Dennis uses photographs as general memory aids, not records of complete detail.

[10] Herschell B. Chipp. Theories of Modern Art. Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press, 1970, p. 132.

[11] Thomas Mallon, “The Historical Novelist’s Burden of Truth,” in In Fact: Essays on Writers and Writing. New York: Pantheon Books, 2001, p. 291.

[12] Often misquoted as “Painting is a lie that tells the truth,” Picasso’s comment comes from a 1923 interview with Maurice de Zayas. See Herschell B. Chipp. Theories of Modern Art. Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press, 1970, p. 264.

[13] “…it is a condition of literature’s wider truth to life that it is not exclusively cognitive; that it covers the whole range of human actions and feelings, memories, and imaginings; and to treat literature as cognitive both in subject and meaning is not only to misrepresent it, but to prevent it from fulfilling its capacity to enlarge our imaginative sympathies.” Robert M. Polhemus and Roger Hinkle, “Introduction,” in Critical reconstructions: The Relationship of Fiction and Life. Stanford, California: Stanford University press, 1994, p. 3.

[14] Gary Snyder reminds us that “The immediate timeframe of human experience is the climates and ecologies of the Holocene---the ‘present moment,” the ten or eleven thousand years since the last ice age.” Gary Snyder, “Tawny Grammer,” in The Practice of the Wild. San Francisco: North Point Press, 1990, p. 73.

March 11, 2015