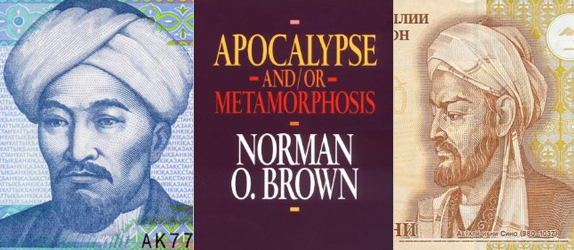

Al-Kindi, Al-Farabi, Avicenna, three of the most important men of the Islamic Golden Age—but how many of us know these names; or know what they wrote or practiced, or how they contributed to the knowledge of the West?

Perhaps the most famous, Ali ibn Sina, Latinized to Avicenna, was a Persian polymath, who wrote numerous texts on philosophy and medicine; he died in 1037 ce.

Al-Farabi, another Persian, died at Damascus in 951 ce. Another great scientist and philosopher, he was known as “The Second Teacher,” meaning he was the successor to Aristotle.

And the Father of Arab Philosophy, Al-Kindi, translated Greek scientific and philosophical texts into Arabic, thus preserving ancient classical knowledge. He died in 873 ce.

How many non-Muslims in this country have ever read the Quran? When you consider that the Protest-ants began their split with the Roman church almost five centuries ago, yet in today’s Islamic world the sects of this religion are waging bloody battles against one another, as witnessed in Iraq today, it becomes clear that these internecine disputes are not just about dogma, they are about politics. All sides adore Allah.

Muslims believe that the Quran (literally “the recitation”) was verbally revealed from God to Muhammad through the angel Gabriel, gradually over a period of approximately 23 years, beginning on December 22, 609 CE, when Muhammad was 40, and concluding in 632 CE, the year of his death.

Although I studied medieval Arabic thought and philosophy in college, and became familiar with those aforementioned savants, I am not an expert in this field; but recently I have been reading an American scholar who, in his own prophetic tradition, outlined the most basic goals of Islam for us in a book published in 1991.

In Apocalypse and/or Metamorphosis, Norman O. Brown offers us a partial exegesis of certain texts that seem to have great value in order to form an understanding of a religion that has 1.6 billion members worldwide (2012).

He quotes experts, who themselves are profound. One, H.J. Schoeps, when talking about Mohammed, says “Thus we have a paradox of world-historical proportions, viz., the fact that Jewish Christianity indeed disappeared within the Christian church, but was preserved in Islam and thereby extended some of its basic ideas even in to our own day.”

Islam fervently professes the prophets, Abraham, Ishmael, Isaac—including Jesus—they make no distinctions. I am not going to delve into the schism between the Shiites and the Sunni Muslims who are waging deadly war in Iraq as I write this. 1

However, John “Juan” Cole, a well-known historian of the Middle East, has pointed out on his blog, Informed Comment, that the split between Sunni and Shiites in Iraq is of relatively recent origin:

I see a lot of pundits and politicians saying that Sunnis and Shiites in Iraq have been fighting for a millennium. We need better history than that. The Shiite tribes of the south probably only converted to Shiism in the past 200 years. And, Sunni-Shiite riots per se were rare in 20th century Iraq. Sunnis and Shiites cooperated in the 1920 rebellion against the British. If you read the newspapers in the 1950s and 1960s, you don't see anything about Sunni-Shiite riots. There were peasant/landlord struggles or communists versus Baathists. The kind of sectarian fighting we're seeing now in Iraq is new in its scale and ferocity, and it was the Americans who unleashed it.

Brown says, “Islam represents a return to the original Mosaic theocratic or theopolitical idea. The kingdom of God is a real kingdom on earth. The dualism between temporal and spiritual regimen is rejected…Prophetic revelation has to replace Roman law with its own law: ‘The Law, which is the constitution of the Community, cannot be other than the Will of God, revealed through the Prophet.’ The prophetic movement then,” Brown continues, “has to be a political revolution: Mohammed is the prophet armed;” and then, in what may be the most important aspect of forming an understanding of this “religion of peace” he writes, “At the same time the Mosaic theocratic idea is freed from its national (ethnic) limitations and given new and revolutionary content as a program for instituting theocratic world government.”

Using Dante’s “glorious idealism” from De Monarchia, which Brown says is pure Islam: “Of all things ordained for our happiness, the greatest is universal peace”; “To achieve this state of universal well-being a single world-government is necessary”; and “Man is by nature in God’s likeness and therefore should, like God, be one”. He says that Mohammed toward the end of his life called on the empires of the world to submit to the rule of God. “Prophet against empire: but Prophet armed.”

There is so much more in this book; as when he says that the total history of Islam, including its failures, is “not enough studied by Marxists or Muslims.” Or in explaining that “Shariah” (“Law”) on the one hand, and “Tariqah,” the spiritual path, the mystic way (“Sufism”) on the other; the two great symbols of Islamic aspiration and achievement.”

Islam also rejects the Trinity of the Christians. “‘Say not Three; He is One; He begetteth not; Surely they are unbelievers who say God is the Messiah, son of Mary.’ ” This singularly sets Christianity and its most basic tenets at odds with Islam. There can be no compromise, except to make Jesus a mere prophet, not the Son of God.

Democracy, in its dialectical achievement since Aristotle re-wrote the Greek constitution in 350 bce, has established itself in this nation on the basis of the Constitution and the Amendments, the first one being: Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof…

In the prophetic tradition of Islam, our liberal constitution stands in direct opposition to the Law of the Prophet. Democracy and Islam are antithetical to each other. This is what I garnered from Brown’s study, that no matter what there can be no reconciliation between these two systems, and that only political solutions will prevail, and not, as our recent wars have shown, a propensity for violence. Those tactics are from the Crusades. Educational and economic opportunity, and diplomacy will go a long way to keeping radical Islam from spreading further around the globe. This is in the interest of democratic people everywhere.

1 When I began writing this I didn’t think it would become relevant so quickly, but now President Obama is committing more U.S. troops to Iraq; but with all of the “experts” in the White House you would think that they know about Islam, and what is driving this war in Syria and Iraq. The West cannot be the arbiter of this battle between these sects.

The problem is the West has caused these geo-political disruptions going back to Sykes-Picot in 1916, and continuing all the way up to today. A partition of Iraq is one answer, but that would legitimize a radical Islamic state run by ISIS. This idea will not prevail, and violence will be our response, leading to more failure.

Responses to “The Prophet Armed: The writings of Norman O. Brown”