Editor’s Note: In this two-part series New Mexico Mercury and La Jicarita have joined forces to look deep into the so-called “reform” movement in education across the country and in New Mexico. Part 1 is written by Kay Matthews and appears today in both the Mercury and La Jicarita. Part 2 will be published on Thursday. La Jicarita is an online magazine of environmental politics based in northern New Mexico.

Part 1: The Roots of Reform: A Neoliberal Agenda

" . . . what is happening now is an astonishing development. It is not meant to reform public education but is a deliberate effort to replace public education with a privately managed free market system of schooling."

That’s Diane Ravitch (Reign of Error: The Hoax of the Privatization Movement and the Danger to American’s Public Schools), one of leading voices in the campaign to discredit the movement that claims our schools have “failed” and our only hope is to deliver them into private hands and corporations that can run them efficiently—and profitably. Por qué no? They’ve already privatized our prisons, post offices, and the military. Why not our children’s education?

That’s Diane Ravitch (Reign of Error: The Hoax of the Privatization Movement and the Danger to American’s Public Schools), one of leading voices in the campaign to discredit the movement that claims our schools have “failed” and our only hope is to deliver them into private hands and corporations that can run them efficiently—and profitably. Por qué no? They’ve already privatized our prisons, post offices, and the military. Why not our children’s education?

There are many others engaged in this grassroots campaign along with Ravitch: teachers, principals, unions, parents, children, and other taxpayers. Almost every day there’s something in my e-mail or on Facebook about folks fighting back, both nationally and here in New Mexico. Governor Susana Martinez, as New Mexico Mercury writer Benito Aragon will reveal in Part Two of this article, is one of the governors at the forefront of this movement to capitalize education through testing, vouchers, charter schools, and virtual classrooms.

Reform Equals Privatization

Before we go there, however, let’s take a look at how this “reform” movement began. Not surprisingly, the road leads back to the University of Chicago’s Milton Friedman, the guru of neoliberalism. In his manifesto, Capitalism and Freedom, he laid out the basis of his neoliberal system: privatization, deregulation, and cuts to social services. In 1955 Friedman introduced the idea of vouchers for parents to be “free to choose” their schools and get government out of the way. He proposed this as a solution to Catholic schools complaining that they paid taxes for schools but were prevented from receiving public funding. But the timing of his proposal revealed a more pernicious agenda: the Brown v. Board of Education in 1954 overturned racial segregation in the schools; states that wanted to preserve segregation could use the idea of school choice as a strategy to do so. At the age of 93, a year before he died, Freidman got to see his wishes largely come true. Three months after Hurricane Katrina decimated New Orleans and the Gulf Coast, Freidman wrote an op-ed in the Wall Street Journal saying it was time to “radically reform the educational system.” He wanted government to provide vouchers instead of rebuilding the public schools, and President George W. Bush provided tens of millions of dollars to set up privately run charter schools. The teacher’s union was broken and all its members were fired. Eighty percent of students in New Orleans are now in charter schools.

The Chicago School of economics has been gaining traction around the world (see Naomi Klein’s The Shock Doctrine: the Rise of Disaster Capitalism) and in this country since Ronald Reagan’s presidency. In the late 1980s, a group of the nation’s leading CEOs, the Business Roundtable—Chevron, Signa, Charles Schwab, Campbell’s, FedEX, General Mills, Merck, you get the picture—got together to talk about “our failing schools.” Kathy Emory, an academic and education expert, explains that the group proposed state legislatures adopt legislation that would impose “outcome-based education,” “high expectations for all children,” “rewards and penalties for individual schools,” “greater school-based decision making,” and align staff development with these action items. Over the course of the next few years the group agreed to “nine essential components,” the first three of which—state standards, state tests, and sanctions—were adopted by 16 state legislatures as part of their high stakes testing agenda. By this time the CEOs had recruited a broad range of collaborators in their plan: the Education Trust, Annenberg Center, Harvard Graduate School, Public Agenda, Achieve, Inc., Education Commission of the States, the Broad Foundation, Institute for Educational Leadership, federally funded regional laboratories, and most newspaper editorial boards.

The Chicago School of economics has been gaining traction around the world (see Naomi Klein’s The Shock Doctrine: the Rise of Disaster Capitalism) and in this country since Ronald Reagan’s presidency. In the late 1980s, a group of the nation’s leading CEOs, the Business Roundtable—Chevron, Signa, Charles Schwab, Campbell’s, FedEX, General Mills, Merck, you get the picture—got together to talk about “our failing schools.” Kathy Emory, an academic and education expert, explains that the group proposed state legislatures adopt legislation that would impose “outcome-based education,” “high expectations for all children,” “rewards and penalties for individual schools,” “greater school-based decision making,” and align staff development with these action items. Over the course of the next few years the group agreed to “nine essential components,” the first three of which—state standards, state tests, and sanctions—were adopted by 16 state legislatures as part of their high stakes testing agenda. By this time the CEOs had recruited a broad range of collaborators in their plan: the Education Trust, Annenberg Center, Harvard Graduate School, Public Agenda, Achieve, Inc., Education Commission of the States, the Broad Foundation, Institute for Educational Leadership, federally funded regional laboratories, and most newspaper editorial boards.

Instrumental in getting these state legislatures to adopt the testing agenda was the behind-the-scenes organization called the American Legislative Exchange Council, or ALEC, which we all know about now because of the Trayvon Martin killing in Florida. The state’s “stand your ground” law that George Zimmerman used in his defence was based on model legislation written by ALEC. In this case, ALEC helped write legislation based on its goals of privatization and free-market enterprise that were adopted by the 16 states, many of whose legislators are members of the group.

Another group, school superintendents dubbing themselves “Chiefs for Change” who lobbied for “reform” is affiliated with Jeb Bush’s Foundation for Excellence in Education, which I wrote about in my La Jicarita article on Hanna Skandera, New Mexico’s Secretary of Education designate, who is connected to both the Foundation and the for-profit Connections Academy, which Benito will discuss in more detail.

The Corporate No Child Left Behind

How did all this translate to the passage of the No Child Left Behind Act, which nationalized and institutionalized this corporate agenda? In Texas, of course, under then Governor George W. Bush. In partnership with a company called Pearson Publishing (a London-based mega-corporation that owns the Financial Times and Penguin Books), which provides just about everything a school might need—textbooks, data management, professional development programs, testing systems, and remedial learning products if students fail the tests—Texas led the way with mandated standardized testing. By the time Pearson’s acquired the National Computer Systems in 2000 it had already signed a $233 million contract with Texas. With the passage of No Child Left Behind in 2001, all states were required to use a standard test to determine how students were learning. Pearson continued buying testing companies, including the testing services division of Harcourt. Last year, Pearson signed yet another contract with Texas to create the state’s newest testing system: the more rigorous “end-of-course” and State of Texas Assessments of Academic Readiness exams.

A key figure in all this Pearson money making is Sandy Kress. As president of the Dallas Independent School District in the early 1990s, Kress was a vocal advocate for testing and one of the main crafters of No Child Left Behind, modeled on the “miracle” he claimed had raised test scores in Texas (more on this later). The federal law required states to use standardized tests but allowed them to decide which test to use, opening up a competitive process for state contracts. Sandy Kress is also a lobbyist for Pearson.

So what exactly does No Child Left Behind (NCLB), which became a federal law in 2001, entail? The law said that all states must test every child annually in grades three through eight in reading and mathematics and report test scores by race, ethnicity, low-income status, disability status, and limited-English proficiency. All schools must prove proficiency on state tests by 2014. How would that happen? States would monitor every group in every school; if any school persistently failed to meet proficiency it would be labeled “in need of improvement” and could have its staff fired, be closed, handed over to state control or private management, or turned into a charter school. Since 2001 the majority of public schools have “failed.” According to Diane Ravitch this included some “highly regarded schools” and schools that enrolled high proportions of students with disabilities and poor and minority students, those least likely to achieve 100 percent efficiency. She provides the example of Massachusetts, a state with the nation’s highest performing students on federal tests, where 80 percent of the schools were classified “failing” by NCLB standards in 2012.

Inherent in NCLB is the opportunity for the private companies to step in, just as Pearson did in Texas, and make money by publishing all the tests, privatizing the charter schools, providing tutoring, etc. The law was supposed to be revised, reauthorized, or scuttled in 2007 but remained in effect, annually renewed by Congress, until Barack Obama was elected president in 2008. Instead of changing course he instituted Race to the Top as part of the economic stimulus package. One hundred billion dollars was earmarked for education, and $5 billion of that went to the competitive Race to the Top under which schools instituted new common standards called Common Core; expanded charter schools; evaluated teachers based on their student test scores; and as in NCLB, fired teachers and closed “low performing” schools. According to Ravitch, it was even worse than NCLB: “it gave full-throated Democratic endorsement to the long-standing Republican agenda of testing, accountability, and choice.”

The Democrats and Race to the Top

Who were these Democrats advising Obama that privatizing our schools was the way to go (just as he extended the privatization of our health system under the Affordable Care Act)? The lead “reformer” was Arne Duncan, former Superintendent of the Chicago schools and now the Secretary of Education, who began closing schools during his tenure in Chicago. As NCLB was renewed annually by Congress and schools continually failed to meet its targets, Duncan offered waivers to states that agreed to comply with the same conditions set by Race to the Top. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation funded the promulgation of the Common Core State Standards just as it funded various components of the NCLB and the media campaign to convince us that our schools were broken and needed all their money to fix them.

Who were these Democrats advising Obama that privatizing our schools was the way to go (just as he extended the privatization of our health system under the Affordable Care Act)? The lead “reformer” was Arne Duncan, former Superintendent of the Chicago schools and now the Secretary of Education, who began closing schools during his tenure in Chicago. As NCLB was renewed annually by Congress and schools continually failed to meet its targets, Duncan offered waivers to states that agreed to comply with the same conditions set by Race to the Top. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation funded the promulgation of the Common Core State Standards just as it funded various components of the NCLB and the media campaign to convince us that our schools were broken and needed all their money to fix them.  This is Melinda Gates on PBS NewsHour in 2012: “If you look back a decade ago, when we started into this work, there wasn’t even a conversation across the nation about the fact that our schools were broken, fundamentally broken. And I think that dialogue has changed. I think the American public has woken up to the fact now that schools are broken. We’re not serving our kids well. They’re not being educated for the—for the technology society.”

This is Melinda Gates on PBS NewsHour in 2012: “If you look back a decade ago, when we started into this work, there wasn’t even a conversation across the nation about the fact that our schools were broken, fundamentally broken. And I think that dialogue has changed. I think the American public has woken up to the fact now that schools are broken. We’re not serving our kids well. They’re not being educated for the—for the technology society.”

Then there’s Rahm Emanuel, current mayor of Chicago and former chief of staff to Obama. Beginning in 2010, when Duncan was the Chicago Superintendent, the city closed 60 neighborhood schools and replaced them with a hundred new schools, or “turnaround” schools that  were controlled by an independent contractor or a department in the school system (supported by the Gates Foundation). In her book Ravitch shows that the results in improvement were open to debate, based on conflicting evaluations, but that for the most part the turnaround schools showed no more success than neighborhood schools in test scores. But Emanuel, in 2012, proceeded to close or “turnaround” 17 more schools, and in 2013 closed an additional 54 schools, including schools that Arne Duncan closed and “turned around” in 2002.

were controlled by an independent contractor or a department in the school system (supported by the Gates Foundation). In her book Ravitch shows that the results in improvement were open to debate, based on conflicting evaluations, but that for the most part the turnaround schools showed no more success than neighborhood schools in test scores. But Emanuel, in 2012, proceeded to close or “turnaround” 17 more schools, and in 2013 closed an additional 54 schools, including schools that Arne Duncan closed and “turned around” in 2002.

Are Schools Failing or are we Failing Them?

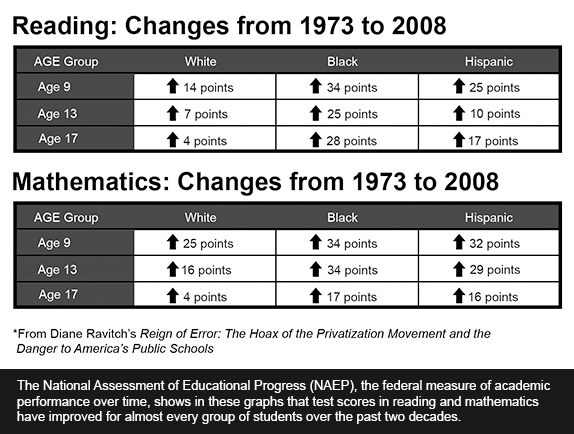

There isn’t much difference between the Republican and Democratic buy-in of school “reform.” How did this idea that our schools are failing gain such across the board traction? Both Ravitch and Kathy Emory provide some important analysis that explains why so many people actually believe that our schools are failing, our educational system needs to be reformed, and that NCLB or Race to the Top is the way to do it.

In this race to privatization the corporate reformers fail to mention that historically our public schools were accessible to only a small percentage of the population: class and race largely determined that percentage. There is little or no discussion that schools reflect the sociological changes in our society, where today’s classrooms include students of every race, every income level, whose first language is not English, and those with disabilities.

In other words, our schools reflect the growing divide between the one percent and the 99 percent, the haves and the have-nots. As poverty levels increase school budgets are slashed and teachers must work with less to do more to address the attendant problems that surface in the classroom: students with emotional and attention problems, students who are hungry, students who are in danger.

Emory sees it not so much as a “failure” on the part of corporate reformers to acknowledge these conditions but as an opportunity to capitalize on them. As our economy transitions from a manufacturing to a service one, she sees our public school system being changed from “one that had tracked students into vocational education and college prep into one that now is tracking students into college prep and dropouts.” As these corporate partners insist that their reforms will get everyone into college to meet the demand for knowledge workers, the reality is that the number of jobs requiring a college degree is not projected to increase in a service-based economy. According to Emory: “So, I suspect that business, experiencing a crisis of profits in the eighties, wanted to increase the number of college educated engineers and computer programmers, not because they expected to see more Americans earn higher salaries but, instead, they wished to increase the supply of college educated workers well beyond the need for them, thereby paying them less. As it turned out, the CEOs couldn’t wait for high stakes testing reforms to achieve this end. So, the CEO’s persuaded congress to dramatically expand the H1-B visa program in the nineties. This allowed CEOs to import high tech workers from other countries paying them half of what their newly unemployed American counterparts had been paid. Today we are just outsourcing the work.”

CEOs have found they can still use this reality to support their reform package of testing and penalties. If a student drops out, it is clearly the fault of his or her teacher. That students continue to drop out and get pushed out in higher and higher numbers is really not a bad result given the job structure of the new economy. Emory quotes statistics from the Monthly Labor Review (November 2005, p.71): “Among the 10 major occupational groups, employment in the 2 largest in 2004—professional and related occupations and service occupations—is projected to increase the fastest and add the most jobs from 2004 to 2014. These major groups, which are on opposite ends of the educational attainment and earnings spectrum, are expected to provide about 60 percent of the total job growth from 2004 to 2014.” [author’s emphasis]

There was no “miracle” in Texas when George Bush and his cohort opened up the public schools to privatization. The state made some improvements on federal tests, like many other states, but its students register at the national average. Michelle Rhee, the darling of the privatization movement who became the chancellor of the Washington D.C. schools and instituted top-down administrating—firing teachers and administrators without school boards’ input or approval (and without documentation), closing schools without public input, ending teacher tenure, and obtaining questionable results in improving student achievement— has been largely discredited. It turns out her tenure was one of “cheating, teaching to bad tests, institutionalized fraud, dumbing down of tests, and a narrowed curriculum” (Ravitch). In Atlanta, Georgia, 35 former educators, principals, and test administrators, under pressure to get the extra federal dollars under NCLB, were indicted on charges of helping students cheat on standardized tests.

There was no “miracle” in Texas when George Bush and his cohort opened up the public schools to privatization. The state made some improvements on federal tests, like many other states, but its students register at the national average. Michelle Rhee, the darling of the privatization movement who became the chancellor of the Washington D.C. schools and instituted top-down administrating—firing teachers and administrators without school boards’ input or approval (and without documentation), closing schools without public input, ending teacher tenure, and obtaining questionable results in improving student achievement— has been largely discredited. It turns out her tenure was one of “cheating, teaching to bad tests, institutionalized fraud, dumbing down of tests, and a narrowed curriculum” (Ravitch). In Atlanta, Georgia, 35 former educators, principals, and test administrators, under pressure to get the extra federal dollars under NCLB, were indicted on charges of helping students cheat on standardized tests.

Here is Diane Ravitch again, in the conclusion to her book:

"Yes, we must improve our schools. Start now; start here, by building the bonds of trust among schools and communities. The essential mission of the public schools is not merely to prepare workers for the global workforce but to prepare citizens with the minds, hearts, and characters to sustain our democracy in the future.

Genuine school reform must be built on hope, not fear; on encouragement, not threats; on inspiration, not compulsion; on trust, not a slavish devotion to data; on support and mutual respect, not a regime of punishment and blame. To be lasting, school reform must rely on collaboration and teamwork among students, parents, teachers, principals, administrators, and local communities."

Responses to “The Invasion of Corporate Education Reform - Part 1”