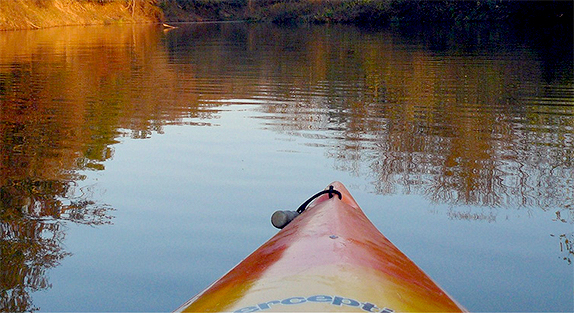

Early on, it was a sunstruck/river spirit day, paddling in a rhythm that doesn't exist for me anywhere else, ever. Dip, pull, feather, switch. Action in the wrist, shoulder, elbow, moving along propelled by my body, my legs braced forward, nursed by the river's current. Incredible green along the banks, healthy huge cottonwoods, silver-green olive trees hanging dead limbs over the water to catch unwary boatmen and sweep them out of their cockpits while immobilizing the boat.

At first I laughed at the sweepers/strainers every time I hit one, which was often and almost always river right. Now that I think of it, a puzzle; there were almost none on river left, and why was that? I thought of this later.

And sometimes in the early hour I just let the kayak go backwards downstream, pretty sure there wouldn't be a danger in watching where I'd come from rather than where I was going. A swift safe waterway, I thought. Naturally I encountered every strainer on the right bank and have the bruises to prove it.

There were more people on the river than I remember from before, little paddle boats with the rudderman or woman and six paddlers, most coming off the racecourse further upstream and I gathered it wasn't much fun; not much water. Six sets of folks in rubber duckies (funyaks) who were intermittently visible; people picnicking in various spaces along the way, under the big trees and featuring the kind of recycled stuff people use to make their picnic places livable and unkempt and crazy but beautiful. Some groups of kids up to their knees or thighs in water. There were many big pumps on river left, but none of them were booming and they looked loud. All quiet. How beautiful the quiet.

Reminded me of the poem of Pablo Neruda: "...And now we will count to twelve and we will all keep still..." Only the riffles of water over small pebbles, the muted ruffled sound as the river crested or separated around a big rock; the birds. There were two duck families, parents sitting on rocks but appearing to be treading water, watching adolescents paddle nearby. Silent blue heron, standing sentinel and flying quietly. Whistles, peeps, chirps, chuckles, all the bird sounds which never disturb quiet for me. Swish of paddle in and out of the water. Nothing more.

Then, later. The wind. The rhythm under the gusts and between the frantic twisting trees became something different. Mind rattled, pissed off, damned wind never like it had to live with all the time when I was a kid fucking wind ruining my day, etc.

The kayak twisted powerfully left and right as strong gusts came off one or another shore. The paddle rhythm changed, now it became ONE (shouted) then dip, pull, feather, FUCK; two, dip, pull, feather FUCK while I fought the damned fall winds blasting upstream, determined to raise the bow, stand me up in the water, and move me backward. I cursed that we had come to the river late in the morning (Mark and his burritos caused this problem) and missed the four hours of quiet rhythmic work that would usually take us from County Line to Embudo.

The signs of summer flash rains, floods and sandy, clay erosion from upper slopes showed under the water where there were sand dunes smoothed into beautiful and treacherous ripples just under the water's surface and they caught the kayak often. This was entirely driver error. I was used to reading the surface of the water and I forgot to look at the telltale color change from greenish and murky to mud-colored and gluey so I spent a grueling time either digging out, rocking out, or walking out and pulling the kayak. Kate eventually did that part because my knees got "bad" and I was pretty seriously immobilized in the kayak once I got down inside the cockpit.

Sometime later in a lull of the wind I thought of "high quality cold water fishery", the government's designation for the cleanest, clearest, healthiest water in New Mexico, given to high mountain streams where the view of a person or a trout is perfectly in focus top to bottom as if seeing through a magnifying glass every pebble and its surroundings, and where the rocks, so visible, offer perfect downside protection for trout eggs and fingerlings.

No sign of that on the Rio Grande yesterday. It was all murky. Reflecting light as always, nurturing green as forever, but gathering up as it must the conditions of its environment, gathering the elements and carrying them or burying them as needed. And here was one dumb kayaker missing the point! There were no sandy, gravel banks so when we stopped and I managed to get out of the craft I sank two or three inches in sucky muck and, tired as I was, didn't have enough power (or leg length) to move. Meanwhile, Kate and Mark with their long powerful legs, walked around as if they were on football turf. Frustrating, humiliating, enraging, etc. etc. So the end of the day, still in the diamond waters and green borders, I was highly irritated, pissed off and clumsy. Fell down twice, once hitting my back on one of the half-hidden rocks.

I want to go back today, right now, and see early in the morning not the golden, diamond light but the murky depth, understanding early in the day how to read the river and stick with the damned fast water wherever it was instead of farting around in those even surfaced hell holes of muck. So there.

(Photo by Thomas and Dianne Jones)

Responses to “A day on the river. Mixed.”